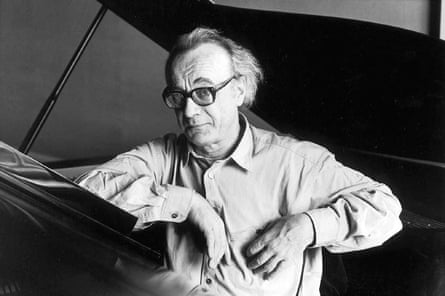

Alfred Brendel would have scorned the suggestion he was the world’s leading pianist. He would have dismissed such an accolade as banal, journalistic and ignorant. He would, of course, have been right. Piano playing, he once said, was never sufficient, even when it was faultless.

Yet, for a generation of musicians, especially in Britain, where he lived the second half of his long life, this dismissal of his own greatness could itself be dismissed as false modesty. When London’s Royal Festival Hall, still at that time the capital’s most cherished classical music large venue, reopened after a long renovation in 2007, the choice of its first recitalist was a no-brainer. For his legions of admirers, Brendel was always the one.

He was the pianist whose recitals they would never miss, the one whose recordings they felt came closest to definitiveness, and he was the artist whose performances seemed unmatched in their objectivity, balance and colour, seriousness and depth. For the listeners of his era, he was, quite simply, the pianist of pianists.

Brendel, who died this week at his London home at the age of 94, was never best known for his piano pyrotechnics. In performance, he eschewed glitz. While some keyboard virtuosi of earlier times have been noted for their performance mannerisms – Horowitz wiping the piano keys with his handkerchief in mid-performance, Rubinstein playing to the gallery with his exaggerated arm movements – Brendel was straight-backed, concentrated, almost severe.

That was the deal. It was the music, not his personality, that the audiences came to hear. Brendel’s technique was of the highest order, but it was always at the service of the music and the listener, not of his own reputation. His piano sound was rich but never overdone, his readings authoritative but never pompous. His performances always had a well-articulated shape and direction, but they were made up of a thousand small choices and touches about phrasing, contrast and tone. He was never an obviously fast player, but as a listener it was hard to keep up with the cascade of detail that always underpinned the whole.

He was known for his authority in the works of the Austro-German masters – Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert in particular – all of them reliable public favourites. As he grew older, his programmes rarely strayed far beyond this Viennese canon, though Haydn, Liszt and Schoenberg were always important to him too. Chopin and Schumann became increasingly rare inclusions.

But Brendel was not, as some insist, the last upholder of the central European piano tradition. For one thing, he always kept up with contemporary music. He revered Harrison Birtwistle. When the Guardian was looking for a new chief music critic in the early 1990s, it was he who recommended Andrew Clements for the job on the grounds of his commitment to new music.

He saw himself as a cosmopolitan who had simply ended up in the UK (he had a house in Hampstead and another in Dorset). Yet the fact that he chose to live here was undeniably flattering, and the compliment was repaid by the fierce and almost reverential loyalty of British audiences. As with Yehudi Menuhin from an earlier generation, and Daniel Barenboim during his young adulthood, Britain embraced Brendel with undisguised affection.

He was always interested in listening to other musicians, which is more than can be said for all soloists. One sometimes saw him at other pianists’ recitals, notably those of the late Maurizio Pollini, and of former pupils including Paul Lewis and Imogen Cooper. His collaborations with singers were rare, but those of us who heard him accompanying Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau in Schubert’s Winterreise cycle (on the stage at Covent Garden in 1985) were rewarded with a partnership of equals.

Piano playing was, of course, the thing he did best and which gave him his fame and his income. But it was only ever one part of his very varied and even eclectic cultural life. Brendel had a vast and individual intellectual hinterland. He was a writer, a poet and a painter as well as a musician, a teacher, a public intellectual and a man of wide sensibilities.

He was famously a lover of the absurd. His poetry showed the influence of the Munich nonsense writer Christian Morgenstern, while his cultural writing sometimes echoed the great Viennese critic Karl Kraus. Although he was not himself Viennese (he was born in the northern Moravian part of present-day Czechia), the Austrian capital drew him in, not merely because he played so much music by Vienna-based composers. Vienna was the city where he chose to give his farewell concert in 2008 – he played Mozart’s early E flat piano concerto K271.

At his home, Brendel had a drawing of a pianist laughing fit to burst in a concert hall filled with intense and serious listeners. This may explain why there was always something both of the undertaker and the clown in his platform appearance. I never met him socially but, while wheeling one of my children in a buggy one winter’s day, I once encountered him walking purposefully across Hampstead Heath, carrying a brand new blue bucket with its price tag attached. Why the bucket? Where could he be taking it? He grinned as we passed one another. Perhaps it was just another private joke. But it seemed, now as it did back then, to embody the duality of the remarkable artist we have just lost.

3 months ago

92

3 months ago

92