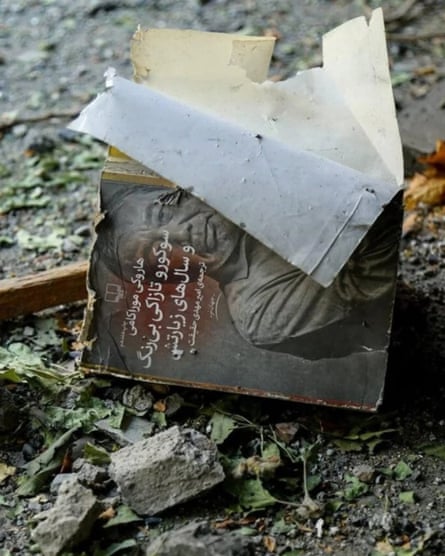

In the rubble of a collapsed apartment block, a single image stayed with me: a book I had translated from English to Persian, lying half-buried in dust and ash. Its cover was torn and smudged, its pages curled and singed, but it was still legible. Still speaking.

Two days earlier, on 13 June 2025, missiles from Israel began striking Tehran. There were no sirens, just sudden, violent blasts. The internet was completely cut off. I was in my apartment, translating Jhumpa Lahiri’s Translating Myself and Others – a book about what it means to transport words across languages, and the ethics and anxieties of inhabiting another’s voice. As buildings fell, I sat editing a text that argued, in its quiet way, for the endurance of meaning.

Everything halted. A book my publisher had been about to send to press was stranded when the printing house shut down. Bookstores closed one by one. One night, when the blasts were too close, my family and I ran down the stairs toward the basement beneath the parking garage. I couldn’t stop thinking about the bookshelves in my apartment, filled with dictionaries, rare volumes I had spent years collecting and every book I had ever translated. That library was my lifework, and I didn’t know if I, or it, would survive the night.

My partner left with her parents for what they thought would be safer towns – places that, days later, were also hit. My daughter travelled to stay in another city with her mother. As her train was pulling out, she sent me a photo: in the distance, a factory was burning, black smoke coiling into the sky. People closest to me were suddenly elsewhere, and danger seemed to follow them.

During those days, moods moved through the city like weather: sudden fear, anxiety, moral outrage at the injustice, then numbness. Beyond the emotional toll, the bombardment dismantled my ability to work. Without electricity and the internet, I had no access to the instant searches and references that translation demands.

Outside, blast waves tore windows from their frames; at my cousin’s house, every pane was shattered, the furniture lay damaged, broken household items scattered throughout the rooms. When I visited, a woman sat before the ruins, painting at an easel, refusing to let silence and dust have the last word.

A photograph circulated on social media of Parnia Abbasi: a young poet, age 23, killed when missiles struck a building. Her poem went viral alongside her image: I will end / I burn / I’ll be that extinguished star.

On a street where I once bought dictionaries, I saw an elderly woman running between alleyways, calling a name. Neighbours said she had lost a son in the Iran-Iraq war over 30 years ago, and now, with Alzheimer’s, the bombs had awakened some buried memory. She was searching for a child who would never come home – in any language.

We were all translating, in our own way: transforming destruction into image, death into verse, grief into search.

A week after the attacks began, still surrounded by destruction, I found myself translating Many Moons – James Thurber’s children’s tale of a king whose daughter will recover only if she can hold the moon. Though written for children, it carried profound meaning for me then. Thurber himself, who lost his sight gradually after a childhood accident yet continued creating until the end of his life, understood something about reaching for the impossible. I wondered if the moon was the peace we all longed for – seemingly unattainable, yet still worth reaching toward.

During those nights of bombardment, I understood translation as something more than literary craft: it was an act of resistance, of staying put, of holding on.

One day, in broad sunlight, blasts hit Evin prison in Tehran; in those same hours, I was translating Lahiri’s passages about the one-time leader of the Italian Communist party, Antonio Gramsci, in his prison cell, asking for more dictionaries, insisting that language study become his “predominant activity”. For Gramsci, translation was – as Lahiri puts it – “a reality, aspiration, discipline, anchor, and metaphor” all at once. He once said that even if he were to be executed, he would spend the night before calmly studying Chinese.

And then came the photograph. I spotted it on a news site and saw that, amid the ruins of another apartment block, lay one of my old translations, scarred but intact, my name printed on the cover. The image was in colour, but it might as well have been black and white, drained of life among the concrete and debris. For most of my career, I had been invisible, as all translators are. But here was my work made visible – scarred, but surviving.

I stared at the image for a long time. Lahiri writes that “all translation is a political act”, but I had never felt the full weight of this until then. To translate, even under bombardment, was to say: “this voice mattered”. It will not be erased. To translate is not just to haul stories across languages, but to help them remain when everything else falls away. It is a quiet, stubborn refusal to disappear.

1 day ago

10

1 day ago

10