When the true-crime documentary Menendez Brothers: Misjudged? aired in 2022 on Discovery+, its impact was not immediate, except on TikTok, where – chicken and egg-style – it was hard to determine whether people were talking about the case because of the show or because a general cultural osmosis had brought the topic to the fore.

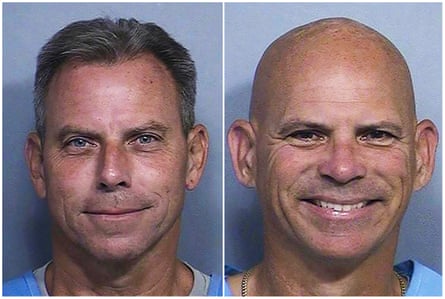

Erik and Lyle killed their parents in 1989, when they were 18 and 21. They alleged a childhood of sexual, psychological and physical abuse by their father, which their mother knew about but didn’t act on. The judge disallowed what was called the “abuse excuse” at the time, and the prosecution successfully landed the argument that they had murdered their parents for their inheritance, resulting in whole-life sentences without the possibility of parole.

Two years later, Netflix brought out the dramatisation Monsters: The Lyle and Erik Menendez Story, closely followed by a documentary, The Menendez Brothers, which featured Erik and Lyle speaking from Donovan correctional cacility. They split the water-cooler crowd. Many felt that, had the brothers been tried today, with our superior understanding of abuse and how it can affect the brain and behaviour, their sentences would have been far less severe. Others still felt that given how rich the family was (their estate was worth about $14m at the time), cash was most likely the real motive; and as for the rest, the only people who could contest the charges of abuse were dead.

A California judge yesterday brought their sentence down to 50 years to life, which makes them immediately eligible for parole since the crimes took place before they were 25. The judge framed his decision not as some post-hoc adjudication on the credibility of their abuse claims, but rather because “they’ve done enough in the past 35 years” to earn their chance at freedom. The brothers also said they have taken “full responsibility” for the murders. The interplay between true-crime drama and the judicial process is simultaneously very subtle and incredibly pronounced.

Drama, whether it is based on a true story or merely a truthy one, influences outcomes all the time, and we are always freshly surprised as though it’s unprecedented. Mr Bates v the Post Office, which said nothing that hadn’t already been unearthed by media investigations, animated that injustice to such an extent that it briefly stood in for everything dishonest in faceless institutions. By the start of this year, many of the 4,000 victims of the Horizon scandal had still not been compensated, and there were more than 2,000 new claims – so it was by no means a perfect delivery of justice via ITV, but it was still important.

Of another Netflix show, Adolescence, the even more abstract claim was made that it “started the conversation” about kids today and how they relate to one another, to social media, to the world. When you look at much more concrete consequences – Ken Loach’s Cathy Come Home, in 1966, led to the establishment of Shelter that year and then invigorated provision of social housing in the decade after – they often stand as a dispiriting reminder that it takes more than fervent public opinion to bed in a social principle. The late Dawn Foster wrote furiously in 2016 that, “We did not learn from the [drama] … Fifty years on, the government has pushed through a Housing Act that seems destined to create thousands more Cathys across the country.”

It takes astronomical humility for the law to rethink its verdicts on the basis of what is, in essence, entertainment. A programme uncovering new evidence isn’t unheard of, but just as often what it uncovers is a paucity of existing evidence.

The first season of the podcast Serial, covering the case of Adnan Syed, who was convicted in 1999 of killing his girlfriend, Hae Min Lee, helped pave the way for his resentencing, though his conviction still stands – he has been out of prison since 2022. The podcast and its aftermath were a rollercoaster of mystery, outrage, triumph and disaster, so that it fell to Young Lee, Hae Min’s brother, to remind everyone: “This isn’t a podcast for me. It’s real life.” The outcome of In the Dark, about Curtis Flowers, the American tried six times for a murder he didn’t do, had a much more satisfying outcome: in 2019, a year after the podcast aired, its details in essence a grisly narrative of racial injustice, Flowers was released, and charges against him were formally dropped the following year.

Ultimately, neither Menendez documentary proved motive, and neither led to this possibility of parole. Did the chance to speak and be heard on Netflix allow the brothers eventually to voice the remorse that the judge found decisive? That would be hard to prove. But true crime, at its best, fosters curiosity in the putatively open-and-shut, empathy for the supposedly worst, and reminds us that people shouldn’t be forgotten entirely, whatever their crime. It’s an adjunct to the law, not a thorn in its side.

-

Zoe Williams is a Guardian columnist

4 hours ago

5

4 hours ago

5