There is some mystery surrounding Donald Trump’s moves to dismantle many cherished principles of American history and its culture of governance: his globalization denialism; his romance with Russia; his demolition of universities; his contempt for European values and histories; his campaign to humiliate Canada. These are all known examples, but it can be hard to see across them to discern anything like a unified theory of Trumpism.

There are two possibilities here. One is that there is no rhyme or reason to Trump’s actions. He is simply a randomizing generator of chaos. The other is that there is a method.

I subscribe to the second possibility. I think Trump – and his advisers – know what they are doing.

Other tinpot dictators – like Narendra Modi, Recep Erdoğan, Vladimir Putin, Xi Jinping, Viktor Orbán – and their countries are distinct from the US in an important way. These autocrats around the world do not have comparable democratic institutions. They can capture, subvert or sabotage democratic traditions in their own countries, using their own means. In each of them, there are longstanding traditions of inequality (such as caste in India), vigorous and celebrated imperial histories (Turkey, Russia and China) and deep traditions of racial and religious nationalism (Hungary and India).

But they do not have the special strengths of American democracy: a sturdy commitment to separation of church and state; the distribution of powers between legislature, judiciary and executive; and a deep antipathy towards tyrants, royal or otherwise.

Trump thus comes to his dictatorship fantasy – evidenced by his compulsive impatience with advisers, media critics, political opponents or ordinary citizens who question him, and a bottomless appetite for praise and fealty – faced with a globally unmatched set of institutional powers that could theoretically stand in his way. To defeat them, he has hit upon an original formula: to reverse-engineer the liberal institutions designed as guardrails against people like him.

The institutions that require repurposing include the world’s most powerful judicial and legislative apparatus, which were designed to keep the executive restrained; a vast body of law and regulation; a massive federal bureaucracy to assure that federal policies are scrupulously enforced; and the world’s largest combination of military and police forces to help the state to assure domestic order and civility. Trump is turning these watchdogs into his personal pets.

Trump’s scorched-earth approach to these institutions, their norms and powers, is not designed to improve the originals but to gut them, in part by turning their powers against themselves.

The advanced civic infrastructure of the US could not easily be turned against itself. It required careful planning over the Joe Biden years by Trump-allied strategists, thinktanks, policy wonks and planners. During this period, every ideological cough from Trump was turned by these adjunct players into a menu of detailed executive actions.

Trump and his supporters, spread across a hefty network of rightwing thinktanks as highbrow as the Heritage Foundation and as lowbrow as Breitbart, have been busy for at least a decade laying the foundations of the greatest democratic rollback in US history, designing a newly minted form of jiu-jitsu to undo the grand American democratic tradition. This form of jiu-jitsu puts law against law, police forces against other police forces, court against court, media campaigns against other media campaigns, science against science, religion against religion, and deals against markets.

Thus Ice is ranged against more conventional police departments, the FBI has been internally polarized, pro-Israel evangelical Christians are turned against more liberal Christians, university trustees are turned against faculty, Robert F Kennedy’s lunatic science is turned against the scientific mainstream, and the supreme court is pitched against the lower courts willing to check Trump’s power.

And of course there is Trump’s attack on US higher education, which has been widely dissected, turning universities into hostages of the federal government, and civil rights law into a tool to attack civil rights. It is precisely universities’ commitment to debate as a path to new knowledge that motivates Trump’s effort to take them apart.

The very distinctive pillars of American democracy are being turned into fifth columns. Trump and his allies have created a massive autoimmune disorder – one in which the features of American democracy turn on themselves, re-engineering democracy to kill democracy.

In the social science traditions of the west, the great thinker who built his entire sociology around the distinctive strengths of the western apparatus of government was Max Weber. He used his monumental knowledge of everything from Islamic law and Roman jurisprudence, to Mongol military genius and Puritan doctrines to show how a specific network of institutions came together in the modern west to combine economic, bureaucratic, scientific and governmental rationality.

Weber’s ideas did not immunize him from many legitimate 20th century worries about how politics and science could lead to the death of the human spirit in the west. Detractors warned of the risk that science could be captured by the state; others of technological rationality turning into an iron cage that dilutes creativity and joy.

But Weber did successfully demonstrate that it took many centuries to create the complex web of economic, political and scientific arrangements that persist today in liberal democracies. He was wrong about many things, such as the western monopoly over entrepreneurial capitalism, the special Puritan affinity for economic discipline, and the Hindu indifference to worldly wealth. But he was certainly right that Europe and the US (for which he had considerable admiration) were robust societies whose forms – during his lifetime – were the product of a long historical process that led to the creation of what we now understand as liberal modernity.

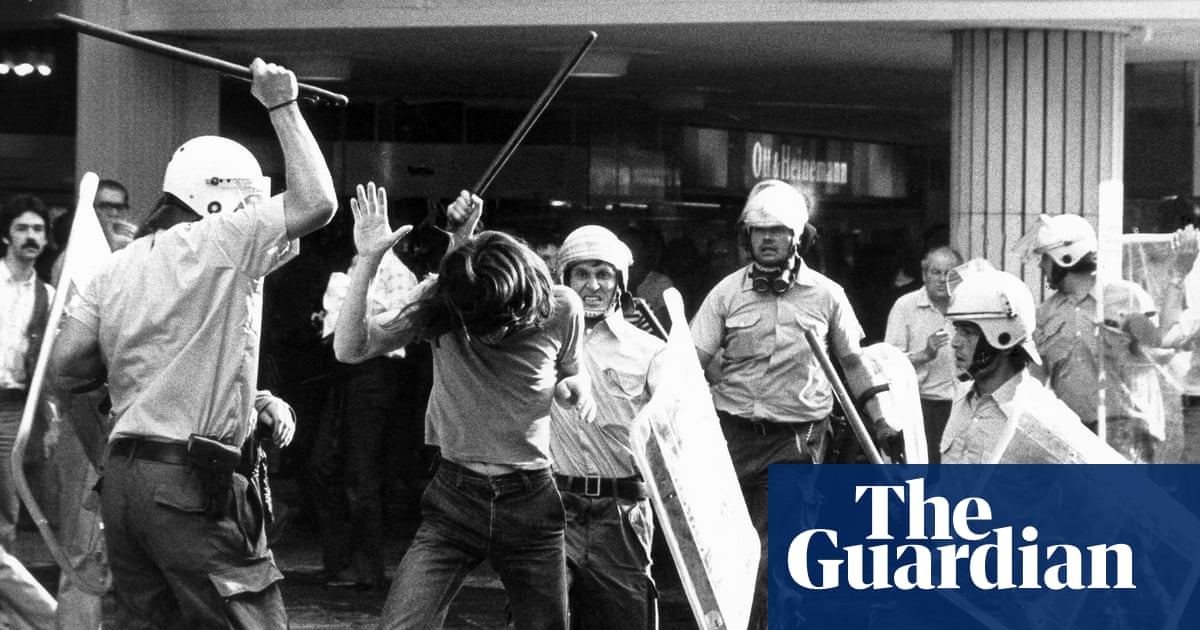

However, the west is not exempt from the truism that it is much easier to destroy institutions than to build them. The rise of the 20th century’s most powerful dictators, such as Adolf Hitler, Joseph Stalin, Mao Zedong, Benito Mussolini and Pol Pot, show us that massive propaganda combined with brute violence can destroy democratic institutions, however recent, fragile and fledgling.

The Trump version of this story is built on the back of 260 years of complex liberal institution-building. To be sure, there are gaping aberrations in this story: a devastating civil war, the persistent enslavement and disenfranchisement of African Americans, racial campaigns against migrants of every stripe and background, paroxysms of rage against organized labor, and virulent anti-communism throughout the 20th century. Nor should we forget the decimation of Native Americans, the crushing of organized labor, the ruthless energy of the open frontier, the rise of robber barons and the cynical abuse of the “right to bear arms”.

Still, American liberal democracy retained a remarkable commitment to representative government and to the separation of powers. It also saw a series of constitutional amendments that moved the needle on the right to vote, on race, on women’s rights, and more. Precisely because of abuses, exemptions and deviations from its constitutional ideals, the civil and political institutions of American democracy looked, until recently, as if they were too resilient to easily destroy. Even Europe, with its monarchs from Britain to Greece, and its 20th-century tyrants such as Hitler, Mussolini and Francisco Franco, cannot boast as resounding a liberal institutional apparatus as the US.

But today, Trump and his army of followers are turning the strengths of American democracy against itself.

Consider the orgy of recent executive orders, which clearly diminish the scope of the relevant constitutional provisions that give Congress the power to legislate. But they are the first in a series of dominos. The use of every kind of lawfare, every form of legal loophole, delay and workaround by Trump’s army of lawyers, takes energy from this initial domino to chip away at the principles of the rule of law, using the law as an autoimmune weapon against all forms of due process. The case of Kilmar Ábrego García, among a multitude of others, shows the president’s readiness to use specious interpretations of the law to play chicken with the supreme court.

Much of this assault can be explained by Trump’s poor education, contempt for liberals, megalomania, personal greed and his unselfconscious vulgarity and lack of any discernible moral compass. But the assaults run deeper than that. Trump wants to produce a new social order as far as possible from the liberal democratic order as he can envision.

More car salesman than capitalist

This brings me to Immanuel Kant, whom I invoke in spite of my knowledge that Trump reads virtually nothing, much less old books or even books about old books. Kant is the key figure who made the connection between Enlightenment universalism and early European liberalism, built around his ideas of reason, autonomy and individuality. The basic Kantian argument is that any rational person who makes judgements as a free individual can see that all human beings deserve to be equally autonomous in order for the overall system to be fair and just. What makes Kant an indispensable post-Christian philosopher is his idea of the categorical imperative, which he explained as follows: “Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law.” In other words, obey those rules that you think should apply to anyone and everyone.

From Kant in the 18th century to John Rawls in the 1970s, the idea that both justice and ethics require what Rawls called the “veil of ignorance” – the principle that a just society requires people to imagine fair social arrangements without any special knowledge of their individual circumstances – has become widely accepted as a foundation for liberal politics, economics and ethics, because it prohibits any individual from making his personal preferences the basis of a collective social policy.

Trump’s ethics (if we can use such a phrase) are diametrically opposed to this principle. His entire view of the social contract is based on his idea of “the deal”. His long-standing attachment to his self-image as a deal-maker has misled many observers to see him as a crude capitalist, as a speculator, or as a conman. But as a deal-maker, Trump is more like the proverbial American car salesman.

In our capitalist commonsense, deal-making is viewed as a direct expression of market ideology, an instance of financial actors making a transaction based on the perceived value of their products, with the agreed price creating a momentary equivalence between the two parties. But it is in fact more akin to barter, which is an evolutionary precursor of the market. It is a primitive form of trade, and when trade broke down in earlier societies, it often led to war. Barter does not require any social contract between the parties, and even less does it require supply and demand, pricing or the invisible hand. It is a face-to-face, immediate transaction, akin to a poker game or an episode of The Apprentice. Markets, on the other hand, are impersonal, abstract, unforgiving. They are not about winners and losers.

This is exactly why Trump’s tariff war feels highly belligerent. It has the tricky logic of barter, where there is no general law of demand or supply, no external source of general price information. It depends on face-to-face relationships, often between parties who may have prior hostilities, major cultural differences, and no shared monetary mechanism to serve as a mediator of value. In this case, mistrust and misunderstanding are ever present during a barter transaction, and any breakdown in communication can lead to conflict, even to war. Trump’s current dealings with many countries have this tense overhang, through which open conflict could break out at any instant.

Trump loves wealth, ostentation and deals, but he hates markets, not because of their imperfections but because they, in principle, rest on religious mysteries – of the “invisible hand”, of supply and demand, of the rationality of prices, all of which are safeguards against political fiat, personal greed and efforts to cook up macro outcomes for micro reasons.

This hatred of markets unites all of today’s autocrats, because markets make their oligarchies unstable and their nationalist fiscal policies responsive to global finance. Hitler was an enemy of market forces both because they could impede state control of the economy, and because he hated Jews whom he saw as the biggest commercial actors behind the market. Stalin despised markets because they thwarted his central planning ambitions. Today, Modi, Erdoğan and Orbán seek to micromanage their economies and have installed loyalists as central bankers, since they fear the power of global financial markets to shake their national economic goals.

It’s not that Trump cares that capitalism enhances inequality, that it is the enemy of planetary sustainability and the most stubborn opponent of economic nationalism of any type. What he disdains is the market – because it obeys no master other than its own rules of price, volume and scale. His weapon against it is tariffs, which he wields in the hopes of bringing it under his control.

The market relies on the social contract, that agreement between individuals and government that is based in trust and predictability. Since Trump despises the market, he must dismantle the social contract, in all its forms and guises.

Any attack on the social contract evokes atavistic fantasies, a return to Thomas Hobbes’s vision of the state of nature, in which human life is nasty, brutish and short. Or it evokes the Nazi version of a pre-contract world, built on racial purity, naturism, savage territorial expansion. Or Stalin’s special brand of paranoid planning, dictated science, and socialist realism in art and culture. Or Pol Pot’s insane literalism in trying to destroy cities, money and intellectuals. Or Mao’s astonishing Great Leap Forward, with its steel furnaces in every backyard and its youth militias wrecking all forms of the class enemy. Each of these regimes hated the social contract, in any of its many Euro-American versions.

But none of them could bring the full force of existing liberal institutions to bear on the pulverizing of the social contract, as Trump is doing today in the US. This is because the vast and interconnected force of law, bureaucracy, economy and state were simply not available in Germany, the Soviet Union, Cambodia and China when dictatorships took shape in these countries. And this was even truer of Latin America, the Middle East and Africa, whose young nations had barely achieved the rudiments of a durable liberal democracy when they were seized by autocrats.

Trump’s twisted genius has enabled the reorganization of the core engineering of American liberal society, to turn its greatest protections against illiberal forces into the biggest weapons of illiberalism. His full-scale demolition of the American social order is based on a remarkable repurposing of the powers of the legislature, of the pesky independence of the courts and of the vaunted guardrails promised by the mass media to seduce many Americans into giving their consent to illiberalism.

The jury is still out on the success of the judiciary in resisting Trump’s suborning of legal institutions, because the supreme court is playing its cards very cautiously. For now, a combination of Trump’s instincts and advisers continue to fuel a major assault on the American liberal democratic order by hot-wiring its basic components. The endgame is to repurpose them as carriers of a massive autoimmune disorder – whereby democracy destroys itself.

Will Trump succeed? Are we doomed to an autocracy in democratic drag? Not necessarily. To resist Trump, we need to rewire democracy to revive democracy. This requires a move away from moral abstractions and liberal hand-wringing to local political campaigning, non-violent civil disobedience and active social mobilization. The clock is ticking and we must not allow the wrong man to be the last one standing.

-

Arjun Appadurai, professor emeritus at New York University, is an anthropologist and former provost of the New School.

-

Spot illustrations by Michael Haddad

3 months ago

306

3 months ago

306