The kills were easier to swallow after a few drinks.

After each operation the police death squads would haunt Manila’s bars to take the edge off, and because some were superstitious, to ward off malevolent spirits following them home.

“Imagine, I kill 47 people and can just sleep? No, I was drinking, drinking just to sleep,” says one. “You need to release stress and we are Filipino … If we go home after killing, the spirit may follow you.”

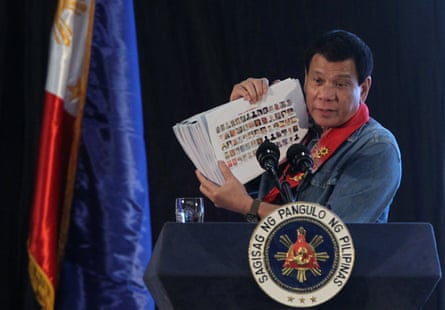

Rights groups believe up to 30,000 alleged drug users and dealers were slaughtered in the so-called drug war that wracked the Philippines after Rodrigo Duterte assumed power in 2016. Many of those killings, it is alleged, were at the hands of secretive police death squads.

Eight years on, Duterte is detained at The Hague, where he has been charged with crimes against humanity at the international criminal court (ICC) for allegedly orchestrating the campaign. But in Manila some police officers involved say their boozy, sleepless nights are over.

The Guardian interviewed four Philippine national police officers, including three former death squad members and one homicide detective, who were part of teams they claim killed about 400 people, including in senseless “vendettas”. As victims’ families long for justice, the officers are largely unrepentant, and across the Philippines a deep affection for Duterte endures.

All the officers interviewed – two of whom have since retired – believe the killing spree was justified. “Bad people”, they agreed, deserve to die.

The Philippine police did not respond to questions from the Guardian but a former police chief who oversaw the campaign previously described allegations of state-sanctioned death squads as “fiction”.

Duterte’s legal counsel at the ICC, Nick Kaufman, said court media policy prevented him from responding in detail to the allegations.

“All I can say is that these recycled allegations are both thoroughly stale and vehemently denied,” he said via email.

“Despite the attempts of a few obstinate politicians bent on destroying his legacy, Mr Duterte continues to enjoy huge support both at home and abroad. He served his country faithfully and with pride.”

Duterte admitted last year to keeping a “death squad” of “gangsters” in Davao – a model the ICC says he later nationalised – but denied as president to ordering police to conduct extrajudicial killings.

‘Thou shall not kill’

Over lunch in a gaudy Manila hotel, one active officer reflected on his role in the drug war, speaking to the Guardian on the condition of anonymity.

Unassuming in glasses and a blue button-up shirt, the officer says most of those killed committed “heinous” crimes such as rape and murder.

“If you are taking drugs and you don’t have money, how will you get your money? You will do nasty things to support your engagement in your drugs. So for me it’s OK, let them die if they deserve to die,” he says nonchalantly over a plate of fried chicken and rice. “An eye for eye, and a tooth for a tooth if they deserve to die.”

Everyone deserves a day in court, he quips, except for “someone who really does not deserve to live”.

“Duterte would always say: ‘If I need to kill you, I will kill you for the safety of most of the people of this country,’ and that is my view also,” he says, adding that he was convinced during Duterte’s time that there was “peace”.

Duterte, a populist and charismatic leader known for his outlandish, sometimes bloodthirsty statements, left office in 2022 but affection for his strongman rule persists.

At the peak of the drug wars, the killings were both incessant and macabre. Night after night, dead bodies were dumped in the street, their heads wrapped in masking tape with placards featuring ominous warnings such as: “Wag tularan Tulak”, or “Don’t be a drug pusher like him”.

Many of those slain were poor and marginalised, their names compiled on watch lists of suspected dealers and users. In theory, the police were meant to verify their activity. In practice, alleged one officer, they were kill lists.

“Under the 10 commandments thou shall not kill,” the officer says, casually continuing to expound his view of justice. “There is no commandment that thou shall not kill drug pushers.”

In the deeply Catholic, Philippines references to the church are never far off, with religion providing solace to both perpetrators and victims.

“Every time I do it I go to the church and make my confession,” the officer says of his efforts to seek absolution.

Initially he was haunted by “flashbacks” and fears of supernatural retribution. Now, he says: “I feel like I am forgiven already. No more bad dreams.”

Even if 30,000 were killed, that’s less than 1% of the population, he calculates indifferently. If anything, he laments, the drug wars delayed his promotion.

The official narrative during the drug wars was that the killings were perpetrated by “vigilantes”, or that people were shot dead by police as suspects fought back after resisting arrest.

Yet within the police, it was allegedly an “open secret” it was an inside job, one retired homicide investigator tells the Guardian.

“When there was a body with a placard, we wouldn’t do a full investigation,” he admits.

“Even though we knew, we just put on the report that it [the body] was dumped … we knew the police did it.”

Rights groups and victims’ relatives have long claimed there was no due process, no arrests or charges, or that crime scenes were staged or tampered with.

The homicide investigator says that when they saw a gun at the scene, police would automatically write “nanlaban”, referring to a suspect fighting back.

“It was just a scenario,” he says of reports he personally falsified.

In his retirement now, he has no regrets. “I’m very proud of myself because so many people died,” he says. “Hopefully many more die again. There are still a lot of bad people.”

“They never fought back,” another retired death squad member alleges. “There was no gunpowder on their hands. But no one dared to investigate, they were scared of Duterte.”

As names on the “kill lists” were exhausted, the hits increasingly became personal vendettas, he says, with names supplied by informants to fulfil alleged quotas set for police stations.

“I feel guilty about that,” he says.

His team would seize suspects and take them back to the station and if no one came looking for them in two days, he says, they would be taken in a car and shot at close range in the back seat. Later they dumped the bodies in areas without CCTV.

“I hated that car,” he says. “It smelt of blood.”

‘Cult following’

Among the more than 14 million residents of Metro Manila, a fondness for Duterte lingers years after he left office. Asked who was her favourite Philippine president, 67-year-old coconut seller Osephina Gabriel, was unequivocal. “Duterte,” she says. “He has a strong hand.

“There were no criminals when he was president. During Duterte’s time there was no petty crime at night. There was peace.”

The deaths, she shrugs, were necessary collateral and Duterte “did what he had to do.”

It is a refrain oft repeated by Filipinos, who say they felt safer even as thousands were killed as they slept.

Criticised abroad, Duterte’s common-man image is part of his lasting appeal at home. A Pulse Asia Research survey conducted in May showed that 63% of Filipinos trust Duterte.

So entrenched is the affection that in May the 80-year-old won his bid to become Davao mayor while imprisoned at The Hague.

“I questioned why he was arrested,” says pedicab driver Antonio Arregio. “Maybe it was because of politics.”

“We’re still in the midst of this propaganda war with the Dutertes who propagated the myth of the war on drugs,” says former senator Antonio Trillanes of a leader he argues created a “cult following” through “deception, misinformation and fear”.

“He was very charismatic, to the point that he was able to convince them that this is morally justified,” he says.

The reckoning

When Duterte was arrested in March, Teresita Beranal felt the first glimmer of hope that justice might finally be served.

In August 2017 her son was shot dead by four men who dragged his dead body through the neighbourhood “like a pig”.

“I know many others who also lost their children. I can’t count,” she says. “I hope we can get justice. Our loved ones are not animals.”

But with the exception of a few egregious cases, accountability remains elusive and investigations slow going. Few officers have been found guilty, or even tried.

The Philippine commission of human rights (CHR) is working to obtain thousands of related police reports, but it is an inherently fraught exercise.

“It’s a challenge because almost all police stations were involved during the drug war in one way or another,” says CHR’s chairperson, Richard Palpal-latoc.

Overall, any kind of national reckoning appears a long way off.

Journalist and author Patricia Evangelista says: “To expect that the nation does a sudden turn about a man they love, a man they worship, just because he has been taken by an international court … is too much to expect, I think, immediately.”

A poll by Social Weather Stations in February found that only 51% of Filipinos believe Duterte should be held accountable for those killed.

‘70 out of 100’

Reflecting on the crackdown, a fourth officer says he feels disillusioned by the drug wars, but mostly because of his teammates that went rogue.

“They [dealers and criminals] offer you everything – almost heaven – in exchange to protect [them],” he says of his colleagues that switched sides. “All of a sudden you were a warrior in the war on drugs [and then you] become a protector of drug syndicates.”

He doesn’t regret the kills, though, rating his death squad “70 out of 100”.

“What we have done is in the eyes of God and human beings – it’s bad, you know. But on the other side of doing it, it serves the purpose,” he says. “Maybe if they were still alive now, they would still be doing bad things.”

A third death squad member agrees the drug wars degenerated badly in the end.

In a Senate inquiry last October, police officers revealed new details about alleged quotas, and a “reward system”, starting at 20,000 pesos (about $350/£260) a head. Three officers who were interviewed confirmed they received the funds, but said the money was to cover “operational costs” such as stakeouts and petrol, with the lion’s share going to the officer who pulled the trigger.

One officer characterised the funds as “bad luck” money, better spent on drinking than anything else.

Despite their seeming lack of remorse, Duterte’s arrest has stirred a sense of unease among those once on the front line of his bloody campaign.

“Sometimes you are getting nervous,” admits the first officer over lunch.

“If they are running after your boss and he is a statesman who has money to defend himself and he is now in the ICC,” he says, pausing, “what about me? I am just an ordinary Tom, Dick and Harry.”

3 months ago

126

3 months ago

126