From high-end aesthetics clinics to the middle aisle of Lidl, collagen is having a moment. Whether it’s in the form of fruity shots or powdered supplements, this structural protein is being touted as the secret to youthful skin and glossy hair.

Celebrities are also singing the praises of a collagen-boosting procedure called NeoGen, with the actor Leslie Ash claiming earlier this week that it had “taken 10 years off her”.

But amid the glowing endorsements and glossy marketing, a fundamental question remains: can anything else really boost collagen – and is it desirable to do so?

Collagens are a group of proteins that provide structural support and mechanical strength to the gel-like extracellular matrix in skin, cartilage and other body tissues. There are various types, each comprising long chains of amino acids that wind together to form strong fibres called fibrils.

Viewed under an electron microscope, these fibrils form a basket-like mesh in young, healthy skin. But as we age, the amount of collagen declines and its structure becomes more cross-linked and fragmented.

“In younger skin, the fibres tend to be longer and more flexible, but in older skin, they’re shorter and more rigid, primarily as a result of UV damage,” said Prof John Connelly, who studies skin repair and regeneration at Queen Mary University of London.

Collagen is not the only protein that keeps skin looking youthful. Elastin allows skin to stretch and spring back, while other structural proteins help to organise and stabilise collagen. Long sugar chains known as glycosaminoglycans – including the popular skincare ingredient hyaluronic acid – play a key role in hydrating the tissue. Like collagen, these components degrade and change with age, contributing to sagging, reduced plumpness and wrinkles.

Yet collagen continues to dominate the spotlight. Many skincare products list it as an ingredient but “these proteins are very large, so they don’t easily cross the skin barrier when applied topically”, said Prof Tanya Shaw, a spokesperson for the British Skin Foundation and expert in wound healing at King’s College London. That said, collagen in creams may help draw moisture to the skin’s surface, providing a temporary plumping effect.

Collagen drinks are the latest plot twist. Their aim is to supply the raw materials for fibroblasts, the skin cells responsible for collagen production. There was also evidence that fragments of extracellular matrix proteins might act as signals, stimulating fibroblasts to produce not just collagen but also elastin and hyaluronic acid, said Dr Jonathan Kentley, a consultant dermatologist at the Montrose clinic in London and Chelsea and Westminster hospital.

Most collagen supplements use fragments derived from chicken, fish or pork, which are absorbed through the gut and transported to the skin via the bloodstream. However, many are probably broken down further during digestion and it is unclear whether other dietary proteins would offer similar building blocks, according to Connelly and Shaw.

Even if some fragments do reach the skin, they would be working in a damaged environment. “If you start to make new collagen, where does it go, and how does it interact with the existing collagen?” said Dr Mike Sherratt, a skin mechanics expert at the University of Manchester. Also, “if it gets into the bloodstream, it’s not only going to affect the skin, but presumably other organs and tissues as well”.

Animal studies offer some support for collagen supplements: radio-labelled collagen fragments have been shown to reach the skin and boost gene activity linked to collagen production in mice. “Mouse studies have also shown reduced wrinkle formation following UV exposure,” said Kentley.

Some human trials have also reported improved hydration, elasticity, and fewer wrinkles after consuming fish collagen. But most of these were industry-funded and a recent meta-analysis of 23 studies found that only those receiving funding from companies showed significant effects. Kentley said: “When the studies were separated into high-quality and low-quality studies, the high-quality studies showed no skin benefits. So, these results must be interpreted with extreme caution.”

What about medical procedures such as NeoGen? It uses high-frequency radio waves to covert nitrogen gas into plasma (ionised gas), which delivers controlled heat to deeper layers of the skin. Animal studies suggest this controlled thermal damage alters collagen structure, causing skin tightening, and promotes the shedding of surface layers, improving tone and texture.

“Small clinical studies on patients have also shown an improvement in skin tone and wrinkling,” said Kentley. “However, as this is a relatively new technology there is relatively little evidence other than a handful of small studies.”

Other procedures such as microneedling also induce tiny, controlled injuries to the skin, triggering a wound healing response, while injectable “biostimulators” – such as Sculptra – create a foreign body response that stimulates fibroblasts.

While all these procedures have some clinical evidence supporting their ability to stimulate new collagen, the quality is variable and no head-to-head trials have pitted these products and procedures against each other.

Kentley said: “Given that aesthetic medicine is so highly personalised and each product or procedure will have its own benefits and risks, the best way to know what is right for you is by seeing a qualified physician who is not conflicted by the quest for profit.

“In terms of topical treatments, there are decades of evidence to support the use of tretinoin [a prescription-strength retinoid] to boost collagen production and reduce other signs of skin ageing such as pigmentation.”

Although celebrity endorsements and dramatic before-and-after pictures can be persuasive, it is also worth remembering that these procedures are not a permanent fix for skin ageing – they require continuing treatments, which can be costly. The most effective long-term strategy to protect and preserve your collagen is to minimise UV exposure from an early age, through consistent use of sunscreen.

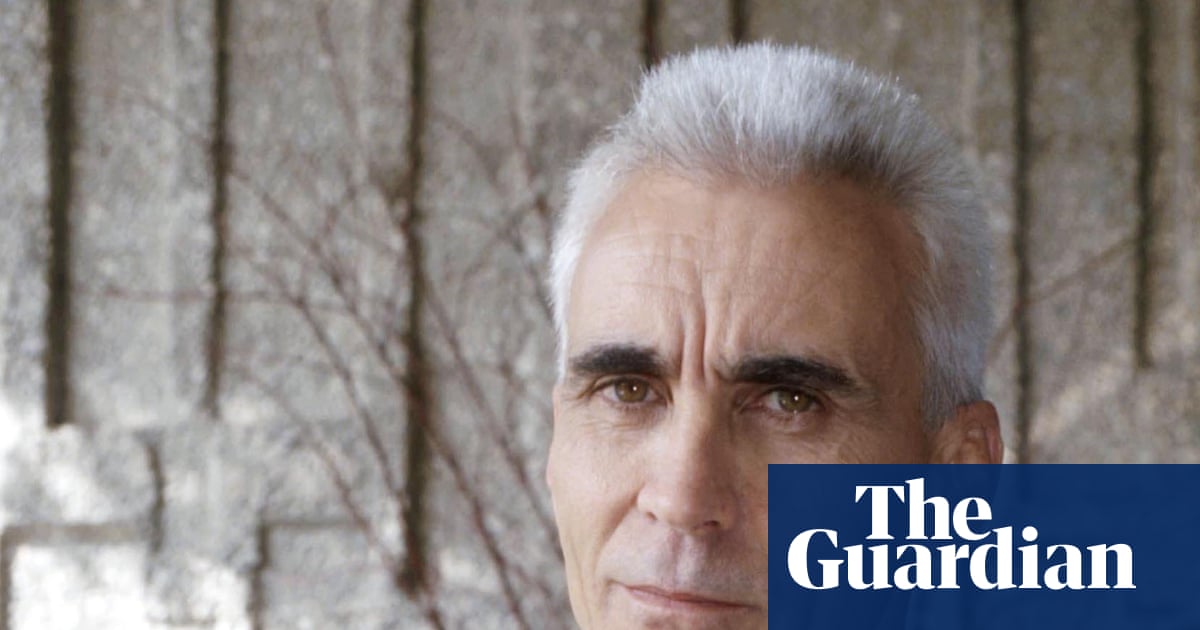

Sherratt showed me a photo of him during Britain’s 1976 heatwave, when he was nine. Unlike the proteins inside our cells that are regularly renewed, he said, type I collagen in the dermis had a half-life of about 15 years and elastin was thought to be meant to last a lifetime. “These proteins accumulate damage over time. So, it’s highly likely that some of the extracellular matrix proteins in my face and forearm still carry damage from that 1976 holiday.”

For those of us who did not faithfully apply sunscreen in our youth, it is worth being realistic about how much even the most advanced treatments can achieve. While they may temporarily firm and smooth the skin, the deeper biological damage has already taken place – and much of it may be irreversible.

3 months ago

73

3 months ago

73