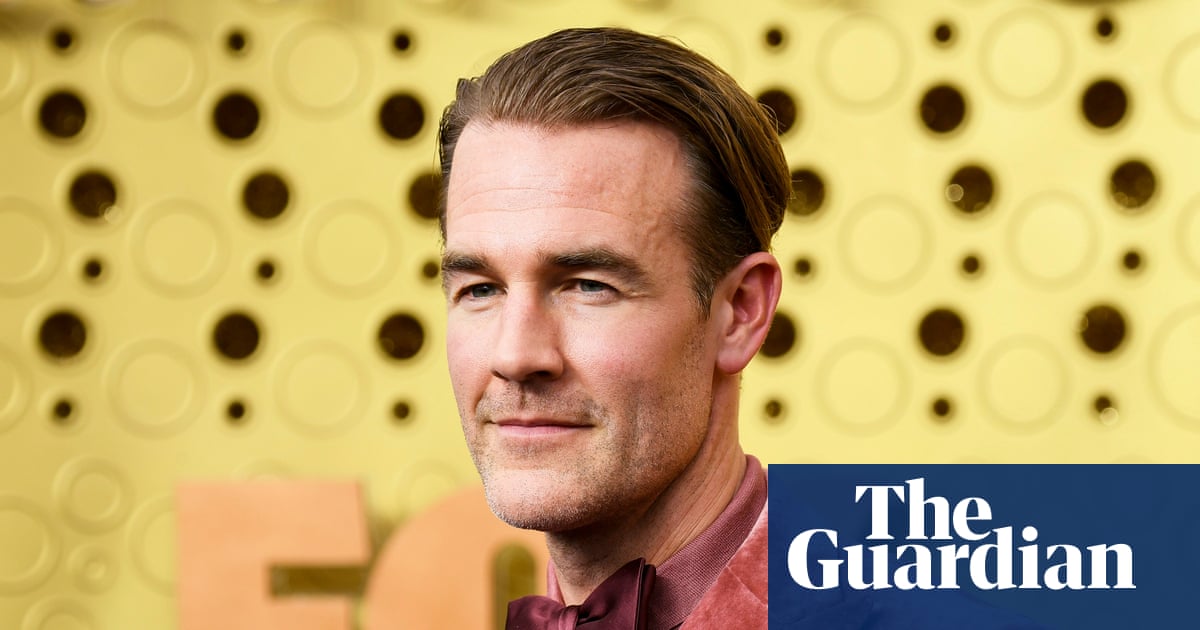

One afternoon in 1984, Farrukh Dhondy went for lunch, not realising he was about to become part of British television history. The Indian-born writer was working for Channel 4 at the time on breakout multi-ethnic shows such as No Problem!, a sitcom about a family of Jamaican heritage in London, and Tandoori Nights, a comedy about an Indian restaurant. When Dhondy arrived at the Ivy, Jeremy Isaacs, the burgeoning broadcaster’s founding chief executive, ordered an £84 bottle of wine.

“I thought, ‘What the hell is this all about?’” Dhondy says. It turned out Isaacs wanted him to be the next commissioning editor for Channel 4. “For God’s sake, I’m not an office job man,” he said. “I’m a writer.” But after a brief conversation with the Trinidadian activist-scholar CLR James, who was living with him while going through a divorce, Dhondy changed his mind.

For the next 13 years, he was part of a radical wave of British TV that funded and supported ethnic minority storytelling in a way that hadn’t been seen before – or since. A new season at the British Film Institute in London, called Constructed, Told, Spoken, will explore this “counter-history”, screening archival episodes that tell the forgotten story of British multi-ethnic programming.

Until the early 1980s, such shows had spoken to audiences of colour without collaborating closely with them. BBC Hindi programmes included Nai Zindagi Naya Jeevan (A New Life, a New Existence) and Apna Hi Ghar Samajhiye (Make Yourself at Home), which focused on assimilation into British life after postwar migration.

“They were extremely patronising,” Dhondy says, citing programmes that, for example, instructed Asian women not to barter at supermarket counters. BBC and ITV sitcoms such as Love Thy Neighbour and Mind Your Language mocked Caribbean and south Asian accents and cultures, and, Dhondy says, the broadcasters’ coverage of 1960s and 70s protest movements was perfunctory and repetitive.

Sarita Malik, professor of media and culture at Brunel University of London, calls that the era of “assimilationist TV”. She explains: “Englishness was always positioned as dominant. [These shows] were geared towards producing a model ‘good minority’. Cultural difference – accent, humour, food, music – was accepted, but political difference was not. [They wanted] a kind of ‘difference without dissent’.”

But dissent they got. Mirroring other anti-racist struggles of the 1970s, activist groups began to draw public and industry attention to racism on TV, with high-profile groups such as the Campaign Against Racism in the Media organising protests against racist programming including The Black and White Minstrel Show, and the Black Media Workers Association threatening strikes due to racism at the BBC. It was time for Britain’s new communities to join the national conversation – broadcasters could no longer afford to overlook them.

Proposed under Labour, Channel 4 was launched in 1982, during Margaret Thatcher’s stint as prime minister, with a radical remit. It had a dedicated multicultural department and, as Britain’s first “publisher broadcaster”, it could commission independent producers who had been excluded from the industry. Mass audience broadcasting was already covered by the BBC and ITV, so the channel chose to serve previously undervalued audiences.

With trade union membership still high and anti-racist organising growing, the broadcaster collaborated with grassroots groups, workers’ movements, activist-writers and independent film-makers under its commissioner of multicultural programmes, Sue Woodford. Dhondy, who was heavily involved in the anti-racist magazine Race Today, the British Black Panthers and the Indian Workers’ association, was well placed to take up this work.

Channel 4 adopted a philosophy called “direct speech”, meaning discussion should come directly from communities rather than mediated through industry professionals. TV was a natural medium for it, an it was still an emerging format by comparison with newspapers. To be truly part of national discourse, people of colour needed a life beyond what Dhondy calls “complaint programmes”: those shows about housing, education and employment that simply point out the existence of racism, as if explaining it to white audiences. “Oh, it’s racism, racism, racism,” he says. “It’s boring. Nobody wants to watch it.” Instead, Dhondy believed we needed sitcoms, drama, documentary, the lot.

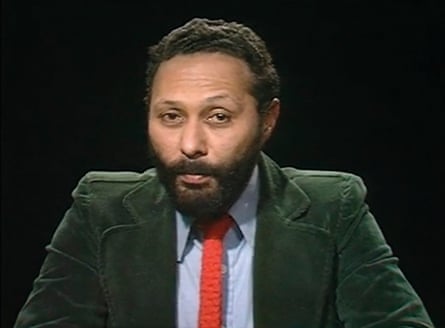

The most famous show to adopt the direct-speech policy in the 1980s was likely Bandung File, commissioned by Dhondy and edited by British-Pakistani writer and film-maker Tariq Ali and Trinidadian British Black Panther Darcus Howe. The documentary and current affairs programme was unique in its attempts to present “third world” and ethnic minority interests to Black, south Asian and white British audiences. Drawing on the political print-reporting of Race Today, Bandung File served communities of colour in practical ways. Programmes took on Black and Asian consumer issues and warned about changes to immigration and naturalisation law.

And the show explored the many facets of racism, beyond caricature. One episode, Too Many Questions, looked at the nuances of racism at Britain’s border, observing that Black people from countries such as Canada are privileged over those from poor, majority-Black countries. The legacy of the show is still precious: Ali last week expressed concern that he had not been invited to speak at its BFI screening next month, fearing the show’s vision would not be communicated (Ali has since been invited).

This era also saw Channel 4’s Asian magazine show Eastern Eye and the African and Caribbean show Black on Black. The latter was the first British programme made by Black journalists –and the team included figures who would go on to achieve other firsts, such as Julian Henriques, the director of the first Black British movie musical, and Victor Romero Evans, star of the first Black musical to hit the West End.

Dhondy says this kind of career progression was built into Channel 4’s strategy of training Black and Asian people as directors, producers and camera crew, as well as actors and presenters. The broadcaster funded small companies led by people of colour, giving them advice on how to get started in the industry, in a bid to decentralise production and get underrepresented communities working behind the camera.

As Channel 4 became famed for its radical programming, the BBC and ITV also diversified their output. The BBC set up a production unit for African-Caribbean shows and launched Ebony, its first dedicated culture review aimed at the Black community. Xavier Alexandre Pillai, curator of the BFI’s season, says part of this interest was economic. “In local markets in the early 80s, programmes were produced to cater to diverse audiences.” When broadcasters were under scrutiny, Pillai says this communicated competence, the feeling “that the appointed broadcaster could be trusted to reach even those audiences considered marginal”.

But by the turn of the millennium, around the time Dhondy decided to leave Channel 4, the economic, political and industry context had changed. The introduction of digital TV and Freeview intensified competition between channels, resulting in increasingly populist and sensationalist programming. Under New Labour, “multiculturalism” once again came to mean assimilation, and more politicised understandings of race fell out of fashion. Channel 4 disbanded its multicultural programming department soon after Dhondy left, and pivoted towards commercial competition. The BBC and ITV followed similar paths.

Despite their ability to provoke pessimism or nostalgia, the broadcasts in the BFI’s season are an important part of British media history, and help contextualise where we are today. When it comes to diversity on TV, broadcasters and critics often reinforce the idea that we are on a steady march towards progress. But this counter-history suggests quite the opposite: that the 80s may be thought of as a golden age for anti-racist TV and that we have, in some ways, gone backwards.

Today, ethnic minorities may feel better represented on the small screen, but as of 2020, they made up only 8% of those working in creative and content production roles, and 9% of those in leadership roles. Dhondy says: “People are taking representation as the ultimate goal. So what you get is Black or mixed-race families doing advertisements selling soap. This doesn’t solve anything.”

The BFI archive also shows the importance of financial and structural investment. The movement for multicultural TV was successful due to dedicated units, huge levels of investment, and worker organising that directly threatened structures of power. The political landscape is different now. “Since the 1980s and 1990s,” says Malik, “we have seen a creeping depoliticisation of the case for more diverse representation – representation without structural challenge.”

Pillai tells me that this is particularly true for nonfiction: “Looking back from the present, it is astounding to see episodes of Ebony where cultural views are unpicked as they interview people of West Indian descent who talk about the complexities of returning to the Caribbean, or TV that provides the historical context of present issues.” He points towards the British media’s failure to contextualise the conditions that led to the 2011 riots as a more recent example of a gap in reporting.

Pillai adds that too few people are aware that all this existed, and that, without this context, we’re at risk of revising history. “[Contemporary] dramas like Small Axe are fantastic, but these historical events are there, captured in real time: interviews with people who were at Grunwick, and coverage of the Deptford fire.”

When we don’t acknowledge these accounts as part of our history, we also tend to paint a picture of the past that is unfairly bleak. “When people talk about representation in that era, the first thing they mention is Love Thy Neighbour or Mind Your Language” – two ITV sitcoms that have since become infamous for their racism. “[That’s] like if historians talked about television in the 00s and only mentioned Jeremy Kyle.”

The reality is always more complicated. As Dhondy says, television is not just one thing – it reflects the national conversation. That conversation is multilayered, contested and not yet concluded. As the archive shows us, it could change at any moment.

6 hours ago

9

6 hours ago

9