There are three kinds of family, muses the novelist and poet Ocean Vuong. There’s the nuclear family, “which often we talk about as the central tenet of American life”. There’s the chosen family, “the pushback”, the community and friendships built by people who have been rejected by their parents, often because of their sexuality or gender identity. And then there’s the family we talk about much less frequently, but spend most of our waking hours within – our colleagues, or what Vuong describes as “the circumstantial family around labour”.

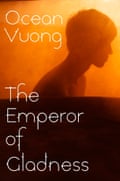

Vuong’s forthcoming second novel, The Emperor of Gladness, encompasses them all. There’s its 19-year‑old hero Hai’s relationship with his mother, a poor Vietnamese immigrant who believes that he has fulfilled her desperate aspirations for him by going to university, when he has actually gone to rehab. (Vuong, who also struggled with drug addiction, didn’t dare tell his mother when he dropped out of a marketing course at Pace University in New York, before getting on to the English literature course at Brooklyn College that set the course for his life as a writer.) The core of the book is Hai’s relationship with Grazina, an elderly widow from Lithuania who has dementia, and who takes him in when she sees him about to throw himself off a bridge in despair. Then there are the eccentric and richly drawn staff members of HomeMarket, the fast food restaurant in which Hai works, with its manager who is an aspiring wrestler, and customers ranging from the snotty and entitled to the homeless and desperate.

Talking in London shortly after Trump’s inauguration, looking every inch the left-field literary lion in a tweed coat, jagged haircut and dangly earring, Vuong says that it’s the special circumstances of our work relationships that make the kind of intimate revelations he depicts in the book possible: “The labour, the anonymity, the long eight-hour shift being this randomised, arbitrary coalescence of people.” He knows what he’s talking about as he used to work in two fast food restaurants in his home town of East Hartford, Connecticut, where he and his mother settled after fleeing Vietnam when Vuong was two, then spending eight months in a refugee camp in the Philippines.

In the restaurants, “I would hear conversations from my co-workers that would blow my mind as a 19-year‑old,” remembers the author, who is now 36. “These private confessions. I’ll always remember I was cleaning the walk-in freezer with one man, about 50. We had our backs to each other, and he said: ‘I can’t tell my wife this; it would kill her. I have three sons, but I’ve realised that I only love one of them.’ If I heard that now, I would probably weep, right? He was trying to give me something, I realise. But at the time I was just like: ‘What is going on?’”

The Emperor of Gladness is a slice of American working-class life that depicts the emotions of its protagonists with a sensitivity and lusciousness familiar to readers of Vuong’s first novel, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous. Published in 2019, that book has sold 500,000 copies in the UK, and 1m copies globally after being printed in 40 languages, making Vuong a literary superstar. As with The Emperor of Gladness, it drew on his own experiences: like its protagonist, Vuong worked illegally in a tobacco farm, while his mother, Lê Kim Hông, had a job in a nail salon. Vuong believes that the chemicals she was exposed to were responsible for her death from breast cancer aged 51.

Vuong’s first-hand experience of hardship animates his writing, which is full of vivid insights into the way the poor in America struggle to survive. The Emperor of Gladness acutely depicts the deceptions inherent in this tough existence, from the “home cooking” at the fast food restaurant, which is actually pre-cooked off‑site and reheated, to Hai’s heartbreaking lies to his mother. “Often, perhaps through theology, we see deception as corrupt,” Vuong says. “But in my life, and what I’m trying to explore in this book is: what is benevolent deception? All these people deceive each other, but they’re trying to help each other, and also trying to get something from each other. We often see folks who are impoverished as passive victims, but it takes an incredible amount of creativity and innovation to survive in the brutal economics of America.”

He is also very attuned to what he calls “chameleonising”, or code-switching, which he says is something that the working poor do all the time. “Growing up in the nail salon answering the phones for my mom, I got to see how people talked, how women would chit-chat with their husbands in the waiting area. And then their husbands would leave, and their voices would change when they spoke to each other. I just thought it was so fascinating.”

Vuong’s mother lived long enough to see his early literary success. He has been showered with accolades, including the MacArthur fellowship (AKA the “genius grant”) and TS Eliot prize, and has an army of readers including many young fans. Director Luca Guadignino depicted the queer, gender-questioning teenagers in his 2020 TV series We Are Who We Are reading Vuong’s poetry collection Night Sky With Exit Wounds, and he was interviewed on a podcast by an audibly overawed Sam Smith. Björk loved his work so much that she wrote to his agent asking to meet him, and the pair have since become friends, not least because when they met late in 2019, Vuong’s mother would die within a month, while Björk was grieving for her own mother, who had died six months before. She gives him advice on dealing with fame, which he describes as “one of my biggest challenges”.

When he’s not teaching in New York (he is professor in modern poetry and poetics at New York University), Vuong lives in a 1780s farmhouse in rural Massachusetts with his younger brother, who he took in after their mother’s death, and his long-term partner, lawyer Peter Bienkowski. “I have two dogs sitting by a fire; our friends are local country doctors and farmers,” the author says. “And then I have to do publicity or something, and there’s an audience of a thousand people in an auditorium. I don’t think I’m ever comfortable with it because it gets very parasocial. People feel like they know me. But Björk told me I was doing it right, and to keep it small.” Prizes, he says, “can change your life. They’re economic windfalls” – the MacArthur Grant is worth $625,000 – “but they’re given to the past. They’re not an assessment of who you are.”

His Zen Buddhism also comes into play: Vuong talks about the principle of the eight winds, including prosperity, decline, disgrace, honour, praise, censure, suffering and pleasure. “If you don’t have a strong sense of who you are that roots you, then you’re at the mercy of the winds and you’ll be blown over. But that was a practice I did way before I became an author.”

Vuong’s attitude to fame may be low key, but his approach to writing is not: The Emperor of Gladness is more ambitious and larger in scope than anything he has attempted before. It contains moments of almost unbearable poignancy, not to mention a nightmarish chapter set in an abattoir (mistreatment of animals, he believes, is “the staging ground for the violence that we enact on each other”), but it has great warmth, excursions into areas of popular culture not usually explored by literary fiction (hip-hop, civil-war tourism and yes, wrestling) and even some jokes. “I couldn’t have written this book as a debut,” Vuong says. “I didn’t have the chops. I wanted to use humour – and humour is very hard. If On Earth is the artist’s statement, the kind of philosophical treatise of what I wanted to do, then Emperor is me trying to walk the walk. Walking the walk is harder than talking the talk.”

after newsletter promotion

Vuong, who could not read or write until he was 11 (he suspects that dyslexia ran in his family), says that DH Lawrence was one inspiration for The Emperor of Gladness, which is “about the same size as Sons and Lovers”, deals with working-class anxiety, and doesn’t offer some rags-to-riches-style escape from the grind of poverty. “Lawrence just said no, there’s going to be no improvement; this whole cycle will stay within this place. We will live, we will talk about life and we’ll talk about death here. I think that was quite radical.”

Like Lawrence’s Nottinghamshire, Vuong’s Connecticut is a far cry from the state’s usual public face. “When I was 20 and living in New York, people would say that Connecticut was the place where posh people with sweaters tied over their necks would live, and I said: ‘I don’t know that part,’” Vuong explains. “What I saw was a post-industrial world of immigrants, working people, and the decline that America is only seeing now through social media. There’s a sub-genre of poverty porn on YouTube where people drive through blighted neighbourhoods, and one of them is Hartford. When I saw it, I thought: ‘Wow, that was my childhood and now it’s entertainment.’ The blight that a lot of America is reckoning with now in the social media age, immigrants have seen for 20, 30 years.”

Though the book is rooted in post-industrial America, set in the fictitious town of East Gladness, Conn (“Gladness itself is no more, so it’s East of nothing,” Vuong says)ecticut, The Emperor of Gladness also takes the reader further afield, back in time and to other nations through the memories and preoccupations of its immigrant protagonists. Hai’s cousin Sony, whose family named him after a TV, is obsessed with the American civil war, while Grazina returns to the insurgency against the Soviet occupation of Lithuania in her episodes of dementia. “It was a convenient way to talk about all civil wars,” Vuong says, noting that while America mythologises its own in films such as Gettysburg, “almost every country has had a civil war – England, Vietnam, Korea. It’s that kind of cultural dominance that I’m trying to work against.”

Vuong is also determined to excavate the histories that America is once again attempting to suppress, this time under the guise of a war on “wokeness”. “Oh gosh, look at ‘make America great again’,” he says. “That phrase gestures at memory, but in fact it functions on romantic nostalgia, which is ultimately amnesia. Because if you ask, where’s the ‘again’, no one can point to it.”

What most Americans don’t want to contemplate, Vuong says, is the role of genocide and slavery in the foundation of their country. “I often think the mistake of the left is to focus on Trump too much,” he says. “Trumpism has been here since Andrew Jackson and George Washington. Trump gives people permission not to look back, or to look back selectively. And then ultimately it becomes an authorial agency to forget.”

Vuong was not interested in considering whether or not the staff of HomeMarket would vote for Trump, setting The Emperor of Gladness in 2009. “It was very deliberate to focus on the Obama years, because it was a lot of hopium,” he says. “That quickly deflated when the president we voted in for the people bailed out the corporations. He’s like: they’re too big to fail. And we’re like: oh.” He calls the 2008 presidential election “my first era of political consciousness” and says that it was the first election he participated in.

“I remember when I was at Pace going to an auditorium to watch the debate between Obama and Mitt Romney. It felt as if we were headed towards something completely new. Like it was electric. And then to see that it was really just an oligarchical state once again and perhaps always had been, that Obama was in many ways just another side of the Bush coin – as a millennial, it really deflated a lot of my peers. I think the greatest deception of my life, politically, was the Obama administration.”

Vuong voted for Kamala Harris, but without much enthusiasm. He says that Bernie Sanders was the Democratic presidential candidate that he and his peers regarded as aligned with their political beliefs. “He would have won [in 2016], I think. But somehow they ousted him from that campaign with the shenanigans of the Iowa caucus. And so when Hillary was announced, we’re like: oh, of course, this is the lesser of two evils that we’re always being told about.”

The author has since decided to channel his political activism in other directions. He and Penguin are donating 50c for every pre-order of the US edition (up to $10,000) to the Queer Liberation Library, an organisation that aims to make books with LGBTQ+ themes freely available on its website. This was partly prompted by On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous being removed from libraries by a municipal board in the Conroe independent school district in Texas two years ago, which Vuong and PEN America regarded as a book ban.

The justifications were unclear. “At first they said it’s explicit,” Vuong says. “But then there are a lot of other explicit books – The Catcher in the Rye has a sexual assault in it. There’s a whole group of students who go to challenge these decisions at board meetings. So then they adopted a new thing where they would say there’s a circulation issue, or the books aren’t being checked out. They make it logistical, bureaucratic. I was told that it only takes one person to make that decision, whereas banning for inappropriate material requires a committee. So it’s really dystopian, because people who don’t even read are now controlling the future of children’s literary lives.”

With America becoming more brutally transphobic by the day, I ask Vuong whether his house is a queer oasis. He says that he has hosted a dozen writers who wanted the space to work on their books, an idea modelled on the house of two trans friends who live nearby and have a child. “At first I was very cis about it; I was: Oh, you have a nuclear family,” he says. “But then I started to observe. Every time I went over, there was a new person there. And it was just trans youth who needed a place to be. So I thought: ‘Oh my goodness. We can rethink the nuclear household or property.’ For a lot of my queer friends, it’s so hard to get into writing residencies and to find a place to do their work. A lot of them are economically vulnerable and losing health care [insurance] in between jobs. And I said: look, there’s space. You don’t have to wait for a grant. You don’t even have to look at me. Just go in there and do the work.”

It’s another experiment in the idea of family, Vuong says, since being a writer in America is so tough. “No one helps you make it. So I’ve got an open invitation to my friends – they just have to call. I’ll prep the room. Just come.”

4 hours ago

15

4 hours ago

15