I can’t remember when I first stopped sleeping soundly. Maybe as a child, in the bedroom I initially shared with my brother, Tariq. I would wait for his breathing to quieten, then strain to listen beyond our room in the hope of being the last one awake, and feel myself expanding into the liberating space and solitude. By my early 20s, that childhood game of holding on to wakefulness while others slept began playing out against my will. Sound seemed to be the trigger. It was as if the silence I had tuned into as a child was now a requirement for sleep. Any sound was noise: the burr of the TV from next door, the ticking of a clock in another room. When one layer of sound reduced its volume, another rose from beneath it, each intrusive and underscored by my own unending thoughts. Noise blaring from without and within, until I felt too tired to sleep.

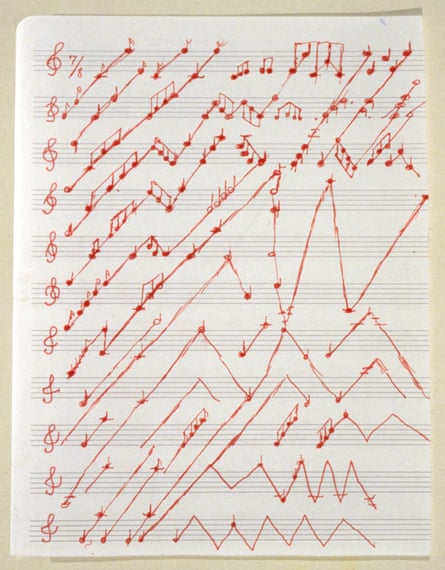

The artist Louise Bourgeois suffered a bad bout of insomnia in the 1990s, during which she created a series of drawings. Among them is an image that features musical notes in red ink, zigzagging across a sheet of paper. They look like the jagged score of an ECG graph that has recorded an alarmingly arrhythmic heartbeat. It sums up the torment of my insomnia: there is a raised heartbeat in every sound.

I have been told that to overcome an inability to sleep you must find its root cause, but this quest for an original impetus is guesswork. Was it self-inflicted in childhood, or does it track further back than that, to infancy, to the womb, to genetics? One starting point is Professor Derk-Jan Dijk’s view of a “sleep personality”, and the idea that childhood sleep habits can be the same later in life. I was born in London, but my family moved to Lahore when I was three years old, before returning to the UK a couple of years later. In Pakistan, there was vigorous, carefree slumber, on the roof of the house on the hottest nights, with the extended family in close proximity. It was sleep as communal ritual. Then the standstill after lunch when everyone lay down again in siesta. I remember my sister, Fauzia, sleeping beside me on these afternoons. There was no hint of insomnia until the move back to Britain when we found ourselves homeless, living in a disused building in north London for a while, crammed into a single room, before moving into a council flat.

In light of Dijk’s words, I see how my insomnia might be a reaction against this early chaos, along with my exacting need for order and silence in adulthood, but that is my own armchair analysis. There are so many gaps in sleep science that I wonder if sleep is by its nature too mysterious to systematise.

If science can’t explain the grey areas around sleep, maybe art can shed a light. It is surprising, given the painting’s sense of joyous night-time, that Van Gogh painted his post-impressionist masterpiece The Starry Night in the midst of depression, after being admitted to an asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence in the summer of 1889. A year before, in a letter dated 16 September 1888, Vincent tells his brother, Theo, that he is doing six to 12 hours of non-stop work, often at night, followed by 12 hours of sleep. By the following year he was in the grip of a “FEARSOME” insomnia. On 9 January 1889, weeks after slicing part of his ear off in a high state of anxiety, he writes to Theo about his torment. He is fighting sleeplessness with a “very, very strong dose of camphor” on his pillow and mattress, he says, and he hopes it will bring an end to the insomnia. “I dare to believe that it won’t recur.” I read Van Gogh’s hope as optimistic desperation. In my case, it has always returned. Yet, even in his “insensible” state, Vincent tells Theo that he is reflecting on the work of Degas, Gauguin and his own art practice; he continues to think, paint, write letters, with the insomnia existing alongside his productivity.

The glittering night sky Van Gogh imagines beyond the confines of his asylum is an embodiment of the way we so often think of the gifted artist at night: synapses fizzing, imagination touched by divinity, a compulsively unsleeping genius channelling a heightened state of buoyant creativity. Countless artists and writers have elected to work after dark, from Toulouse-Lautrec, documenting night revelries at the Moulin Rouge, to Franz Kafka, Philip Guston and Patricia Highsmith. Musicians, too: the Rolling Stones’ all-night jam in the lead-up to their appearance at Knebworth in 1976, for instance; or Prince, whose recording sessions could last across a continuous 24 hours. Certainly, if Van Gogh still suffered from insomnia when he was painting The Starry Night, it makes sleeplessness seem beatific – a curse turned gift.

There is none of this buoyancy in Louise Bourgeois’s night scribblings. She suffered from sleeplessness throughout her life but faced a particularly debilitating bout of night-time anxiety between 1994 and 1995, during which time she made her Insomnia Drawings series. “It is conquerable,” she said, and for her it was conquered, by filling page after page of a drawing diary with deliriously repeated doodles and circles within circles, a mess of scribbles that look like screams on paper. They are so different from the enormous stainless steel, bronze and marble spiders and other caged sculptures for which Bourgeois is better known, but I feel a peculiar kind of excitement upon seeing these images, with their agitating boredom and alertness, side by side.

The artist Lee Krasner also painted her way through chronic insomnia, around the time her mother and then her husband, the painter Jackson Pollock, died – the latter in a drink-driving car crash in 1956, with his lover Ruth Kligman, who survived, in the seat beside him. Krasner’s Night Journeys series has some similarities to Bourgeois’s drawings, featuring repeating, abstract patterns, but washed in an earthy sepia brown. The patterns are insect-like, as if ants are crawling across the retina. I am inspired by the images. Rather than seeking escape or avoidance of their sleepless state, Bourgeois and Krasner stare it in the face, and it stares back at them, an abyss of maddening monotony.

There has only been one instance in my adult life when sleep became easy. Or rather, it became compulsive – as much as the insomnia was, and perhaps even more disturbing. It happened when Fauzia died in 2016, at the age of 45, of undiagnosed tuberculosis. She had been admitted to hospital with an unknown illness, and lay wired to a ventilator in intensive care. When the hospital called to say she had had a fatal brain haemorrhage one morning, the shock of it was too much to take in. So I began to sleep. No amount was enough and I felt increasingly worried by the long, blank nights, which did not bring relief but became as strangely burdensome as the insomnia had once felt.

Haruki Murakami’s novel After Dark features two sisters, the younger, Mari, mourning the older sibling, Eri, who is in a coma-like state. The book takes place over a single night in Tokyo as Mari roams through the city, meeting its nocturnal characters: a trombonist, a Chinese sex worker, the manager of a love hotel. All the while Eri lies in a trapped and mysterious kind of sleep. It might be an undiagnosed illness, a psychological condition or even a radical protest at the world and her place in it – we are never sure.

Mari refuses to see her sister as “dead”, even though there seems no prospect of Eri’s waking up. She looks at her sister’s face and thinks that “consciousness just happens to be missing from it at the moment: it may have gone into hiding, but it must certainly be flowing somewhere out of sight, far below the surface, like a vein of water”. This is how I saw Fauzia as she lay in hospital, after her haemorrhage. Even though we were told she’d remain on a ventilator for 24 hours as a formality before being pronounced dead, I kept watching for her to twitch awake, sure that it would happen. It seemed as if she was in a deep sleep, albeit so submerged by it that she had become unreachable.

In her lifetime, Fauzia went through long bouts of oversleeping brought on by depression. There seemed to be a rebellion in it, too. From the age of 19, when she first became seriously depressed, she began holing herself up in her room, sleeping for the night and most of the following day. In the medieval era, the act of daytime sleeping, for men and for women, was seen to harm one’s reputation. Many still regard it as slovenly and it can be subversive for exactly this reason. For a woman, especially, to refuse to get up and assume her role in the world – which may be one of monotonous domesticity, of caring for others, or of participating in the tedious, lower-rung machinery of capitalist productivity – might be a defiant act of saying “no”.

What might look like inertia, or passivity, can be an active summoning of inner strength, as suggested by Bruno Bettelheim in his psychoanalytic interpretations of fairytales in The Uses of Enchantment. He speaks of Briar Rose (Sleeping Beauty) not as an example of meek femininity but as an adolescent “gathering strength in solitude”. Her sleep is a temporary turning inward in order to foment, mobilise and psychically prepare for the battles of adulthood to come.

A glassy-eyed, self-medicating woman in Ottessa Moshfegh’s novel My Year of Rest and Relaxation also “hibernates” in her New York apartment. She is a Manhattan princess, narcissistic and hard to like, who does not want to experience any of life’s sharp edges. Yet there is something I recognise in her overwhelming desire to disconnect from the terrible reality of the world. She plans to sleep for a year and wake up cured of her sadness, and she is. My sleep wasn’t a cure, but the oversleeping did eventually lift and leave me feeling less numbed to my own sadness. Now I was glad to be returned to myself, and to my insomnia – an old friend, missed.

There is evidence to suggest that women sleep differently from men and feel the effects of insomnia in discrete ways. Professor Dijk cites the familiar list of causes, from lifestyle to social class, wealth and genetics, but he has also found sex-based biological factors, with differences in the brainwaves of women and men when they sleep. Women intrinsically have different circadian rhythms, which are on average six minutes shorter than men’s cycles; they experience more deep (or “slow wave”) sleep and may need to sleep for longer; while a mix of social factors, from breastfeeding to lower-paid shift work, means they face higher levels of insomnia.

Sleep science makes a significant connection between hormones and sleep for women in the throes of menopause. About 50% of women who suffer with insomnia as they approach menopause are thought to sleep for less than six hours a night. The cumulative effects of this sleeplessness can be so intense that some have questioned whether they might be linked to UK female suicide rates, which are at their highest between the ages of 50 and 54.

This brings another kind of insomnia for me, as I turn 50. It creeps duplicitously into my night, so I don’t recognise it; I fall asleep quickly but am awake again at 4am with alarm-clock precision. This is not the organic and woozy “biphasic” interruption believed by some to have been common in the centuries before electric light, in which communities were said to have a first and then a second sleep through the night, getting up to work or chat in between in a brief window referred to as “the watch”. My brain is pin-sharp, as if the sleep before has been entirely restorative and I am ready to start the day, except there is a move towards a certain line of thought, a search for the faultlines of the previous day, the urgent address of an old argument or decision far in the future. And it is, in its scratchy insistence, so much like Bourgeois’s scribbled red balls and Krasner’s insects, that I wonder if they were experiencing menopausal sleep disruption while creating their works.

Whereas younger insomniacs struggle to fall asleep, those in midlife might doze off quickly but wake up in the middle of the night as a result of hormonal changes, and it is in these 4am “reckonings” that they encounter the night-time brain, says Dr Zoe Schaedel, who sits on the British Menopause Society’s medical advisory council. “Our frontal lobe [which regulates logical thought] doesn’t activate as well overnight, and our amygdala [the brain’s command centre for emotions, including fear, rage and anxiety] takes over.” So the very nature of thinking is different at 4am. In the daytime it is primarily logical, but at night we become more rash, anxious, catastrophic. That sets off its own physiological reaction in the nervous system, with a surge of adrenaline and cortisol, as well as rising heart and breathing rates.

Between the waking, there is a welter of dreams, so many it seems like someone is changing between the channels on a TV set. Dr Schaedel says this apparent assault of dreams is an illusion. When oestrogen drops, women start sleeping more lightly and waking up in the latter part of the night, in the shallower REM, or dream, phase, which gives the impression of dreaming more because you are waking up more often in the midst of them.

Still, I am wrongfooted by this second life in my head, this middle-aged night, as busy, as complicated and as exhausting as the day. When insomnia is at its most agitating, engaging the brain visually may be a way to lull ourselves back to sleep, says Dr Schaedel. This idea makes better sense of Bourgeois’s scribbling. Maybe I would find my own recurring patterns on paper if I did the same thing, I think, and so I put a notebook beside my bed. I know I have had a maelstrom of dreams but, when I try to discover them on paper, it is like a stuck sneeze. I write a few words down, but I am left straining for more. A few snatched images come back, but far more float out of view, so much unreachable. The next night I can recall even fewer details, although I know I have dreamed heavily. So my odyssey of dreams evades any attempt at codification. They are determined to remain mysterious, on the other side of daytime.

2 months ago

70

2 months ago

70