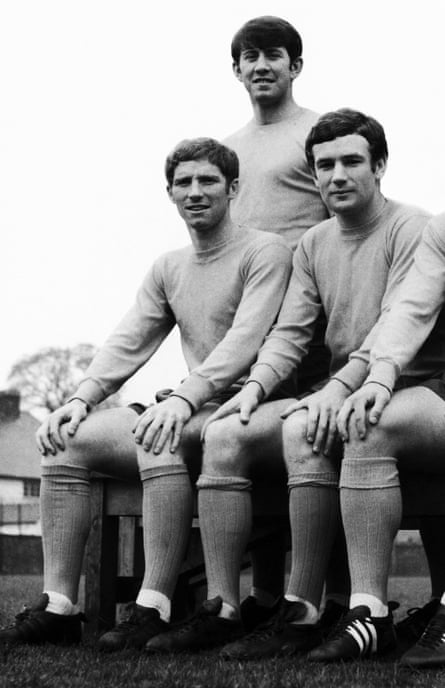

Standing outside a pawnbrokers on Goodison Road, waiting for his dad to emerge through the crowd after the match, a young Colin Harvey could not have imagined what lay in front of him. Standing in the same place today, the great Evertonian would face a statue of himself immortalised alongside fellow members of “The Holy Trinity”, Howard Kendall and Alan Ball. Time has not diminished the 80-year-old’s wonder at his life and legacy at Goodison Park.

“How do you go from being a kid watching Everton from the Boys’ Pen to having a statue on Goodison Road?” he says, with genuine astonishment. “If someone had presented me back then with a history of my life in football I’d have said: ‘Don’t be silly, nothing like that is ever going to happen to me.’ But it did. When I was told the statue was going to be made it was one of my proudest moments. I’ve had a fantastic football life and it amazes me when I look back on it.”

The emotion in Harvey’s voice is clear. There are rich football memories to reflect on as Everton’s men’s team prepares to say goodbye to Goodison after 133 years but it is also a deeply personal place. Family and friends are as much a part of Harvey’s history with the old stadium as starring in Everton’s revered midfield trio, coaching the club in its most successful period, succeeding Kendall as manager and developing a procession of talent as youth coach, Wayne Rooney among them.

No one has given more to Everton than a man whose elegance and technique meant he was referred to as the “White Pelé” in the 1960s, yet who remains one of the most humble individuals you could meet. “From my grandad through to me and now on to my grandchildren, it is our family club,” says Harvey. “Goodison was an iconic place for football. Bellefield [Everton’s former training ground] and Goodison were Everton to me. But time moves on doesn’t it?”

Harvey spent two childhood years living in the shadow of Goodison on Leta Street, one road behind Gwladys Street. Sundays were spent at his grandparents in Fazakerley listening to tales of Dixie Dean’s legendary exploits. “My grandad would say: ‘Modern centre-forwards aren’t any good, Dixie could score with a header from the halfway line,’ and I’d sit there believing it all,” Harvey says with a laugh. “But look at his record [377 goals in 431 Everton appearances], it’s unbelievable in any era. My grandad was probably there when Dixie Dean scored his 60th goal [on the final day of the 1927-28 season]. He worked on the docks so would walk up to Goodison. That’s why Goodison was built where it was, so people could walk to the game. No one had cars when it was first built.”

Harvey’s introduction to Everton was in the early 1950s, the last time the club were outside the top flight, and to what seems another world. His dad, Jim, would go on the Gwladys Street terrace. Harvey and his younger brother, Brian, would go in the Boys’ Pen. Situated in the rear corner of the lower Gwladys Street terrace, it was a floor-to-ceiling cage from which there was no escape. The boys would rendezvous with their dad outside the pawnbrokers afterwards.

“It was Lord of the Flies in there,” he recalls. “The dominant ones stood in the front. I always had to have an eye on my younger brother to make sure he was all right. You were caged in by steel bars. I think the idea was to stop us climbing out and getting in with the adults behind the goal. I remember looking around from the Boys’ Pen and thinking: ‘Blinking heck, Goodison is enormous.’ It held around 70,000 then. But it was cheap. I don’t think it cost even a shilling [the equivalent of 5p today] to get in the Boys’ Pen.”

Harvey emerged from the steel cage into an apprenticeship with Everton in 1961. The training pitch for the A and B teams was behind the Park End Stand at Goodison, next to a small row of terraced houses where players and club employees were sometimes housed. He says: “I started work as an NHS clerk on the Monday and that night Harry Cooke, the old Everton scout, came to our house and offered me apprenticeship forms. My mum said I couldn’t sign because I’d just started a job. I went round to my grandad’s to ask him and he said: ‘You have to give it a go.’ So on the Tuesday I handed my notice in! The head of department said they’d give me two weeks’ notice if they were letting me go, so I expect you to work two weeks. I stayed for the two weeks and went training at night.”

Four months after watching Harry Catterick’s team win the 1963 league title, having run into Goodison to catch the celebrations when the gates opened with 20 minutes remaining, an 18-year-old Harvey made his Everton debut against Inter at San Siro. Everton were knocked out of the European Cup by Helenio Herrera’s eventual champions but the young midfielder received a nice memento from the occasion. “Harry called me up to his office just after my debut. I thought I was going to get a bollocking. Inter had presented Everton with a gramophone as a gift and Harry said: ‘You like your records, don’t you? This is no use to me so you may as well have it.’ So I took the gramophone home. I wish I’d kept it. I probably left it at my mum’s when I got married.”

Harvey has no hesitation in naming the finest player he played with at Goodison. “Oh the best player by a mile is Alan Ball,” he says unequivocally. “Alan Ball is the greatest modern-day footballer at Everton. There have been two greats. I never saw Dixie Dean obviously but his goalscoring record made him a great. In my opinion Bally was the other. After that other players are at varying degrees of greatness but those are the two greatest players to have played for Everton.”

Favourite Goodison memories also come instantaneously to Harvey, though one of his proudest career moments was scoring the winner in the 1966 FA Cup semi-final against Manchester United at Burnden Park. “Seeing Everton win the league in 63. Scoring the goal in 1970 that clinched the league. Coaching with Howard through the 80s was a great period; beating Bayern Munich was an amazing night, winning the championship twice. But my memories of Goodison are mainly about playing there. I loved it. I miss playing there. I wish I’d have appreciated it more at the time. It went so quickly.”

Harvey beat two West Brom players before finding the top corner from outside the box to seal Everton’s 1970 league championship triumph. An abiding memory, however, and one that still moves him, is the scene that unfolded after the final whistle. “We went upstairs to get presented with our medals in the old directors’ box. My dad had made his way through the crowd to the edge of the directors’ box and as I came out to get my medal I saw him. I was a bit emotional anyway with winning the league but to see my dad there, blinking heck, there were real tears then. He was leaning over the edge as we walked through. He gave me a thumbs up.”

after newsletter promotion

Kendall’s decision to promote Harvey from reserve-team to first-team coach in November 1983 is viewed as the kickstart for the most successful period in Everton’s history. The FA Cup, two league championships and the European Cup Winners’ Cup followed over the next four years. The Cup Winners’ Cup semi-final comeback against Bayern in 1985, when Kendall told his players at half-time that the Gwladys Street would “suck the ball in the net”, is widely regarded as Goodison’s greatest night.

“My daughter Mel and my eldest daughter Joanna, who died a few years ago, were in the stands that night and told me afterwards that the ground was shaking,” Harvey says. “The team was like a band of brothers. Even when Bayern took the lead you knew we were going to win. You could just feel it.

“Afterwards John Greig, who had been manager of Rangers, and Alex Ferguson, who was in charge of Aberdeen then, came into the Boot Room for a drink. Jock Stein was already in there with us. The room was quite quiet. When Jock left the other two said: ‘Thank goodness he’s gone.’ They couldn’t speak when he was there because they were so much in awe of him. We were all in awe of him. This is a manager of Rangers and Aberdeen sat with the man who’d won the championship nine years on the trot with Celtic but they hardly said a word while Jock was there. They were made up when he walked out only because it meant they could let their hair down. I’ve never met anyone with an aura like Jock Stein.”

If Bayern was Goodison’s finest night then 3 May 1989 must rank among the most poignant. Liverpool visited to face Harvey’s Everton in their first competitive game since the Hillsborough disaster 18 days earlier. “I was amazed the game was played so quickly,” Harvey says. “I thought football would be suspended until the following season because it was such a profound moment. Playing Liverpool that night was difficult and playing them again in the FA Cup final was too.”

Dean died at a Merseyside derby at Goodison in 1980. Catterick died in similar circumstances almost exactly five years later. “I was at Goodison when Dixie Dean and Harry died,” says Harvey. “The club doctor is a friend of mine, Ian Irving, and he attended to both of them and pronounced them dead. He told me his hands were shaking when he was making the judgment call, that he’d never been so nervous in his life. He couldn’t get over what was happening.”

Harvey will not be involved in Everton’s farewell to Goodison. The hip problems that ended his playing career in 1975 and resulted in two replacements have prevented him from attending a game for 18 months. Walking through an adoring crowd would only aggravate the pain. He paid a private visit to see the banners that had been made in tribute for his 80th birthday in November. Fittingly, they adorned the Gwladys Street end where he once stood. “When I look back I did my very best at everything I did,” he insists. “I wasn’t very good at managing but I did my best and achieved some wonderful memories.”

Everton intend to leave “The Holy Trinity” and Dixie Dean statues where they stand rather than relocate them to Bramley-Moore dock. The bronze Harvey will remain opposite the spot where the young Harvey would wait to meet his dad. “There is a statue of me, Howard Kendall and Alan Ball outside Goodison Park,” says the man responsible for many of the stadium’s most cherished moments. “That’s good enough for me.”

4 hours ago

7

4 hours ago

7