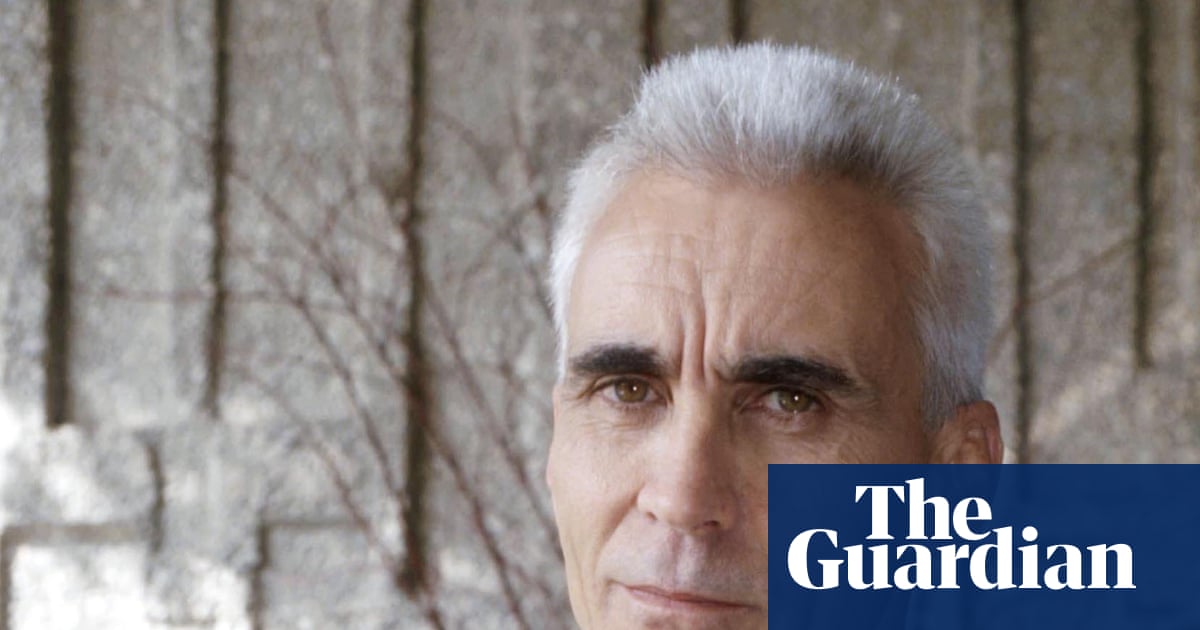

The Bulgarian writer Georgi Gospodinov was published quietly in the Anglophone world for years before he won the 2023 International Booker prize with Time Shelter, about an Alzheimer’s clinic that recreates the past so successfully, it beguiles the wider world.

He is perhaps now Bulgaria’s biggest export. Ever playful, never linear, his new novel Death and the Gardener consists of vignettes of a beloved dying and dead father, told by a narrator who, like Gospodinov, is an author. Gospodinov has spoken publicly about losing his own father recently, and the novel feels autobiographical in tone. When we read “My father was a gardener. Now he is a garden,” it is not the beginning of an Archimboldiesque surrealist tale, but rather a more direct exploration of how we express and where we put our love.

It is harder to write about fathers than about mothers, the narrator says. “The father is a different sort of presence – shadowy, mysterious, sometimes frightening, often absent, clinging to the snorkel of a cigarette, he swims in other waters and clouds.” The book attempts a remedy, capturing a gentle man whose passion is his garden, and the grief of losing him. Odysseus and the biblical Joseph are used as examples of elusive fathers, but not ones without heart. The novel references the episode in Homer’s Odyssey where Odysseus, after years away, watches his aged father, Laertes, tend to his garden, and this book is in a sense an expansion of that particular scene.

Death and the Gardener is also a rebuff to the kind of toxic patriarchal culture that flourished under communist rule. The narrator recalls the story someone told him of a classmate who, when asked by a teacher where his father works, replies “the slap factory”, one of the book’s both sad and funny anecdotes. Communist party officials destroy the narrator’s father’s too-tight trousers and make him cut his own hair and the “Beatles-like” hair of his young sons. The father’s life is one of poverty and lost dreams, but he “managed to turn every place into a garden, every house into a home”.

As the father ages and sickens, the narrator develops a love-hate relationship with his garden. He loves the “buzzing Zen of the bees”, its beauty, the way it is a declaration of love in a culture where “it is not customary to say things like I love you”, but he also thinks “there was some fatal connection, some Faustian deal, between them. I imagined it slowly sucking away his strength, feeding the fruit and roses within it, the rosier the cherries, tulips and tomatoes grew, the paler he became.”

We sit with the narrator in the hospital and at his father’s deathbed. Overwhelmed by medical language – “suspected propagation in the cerebrospinal canal” – he muses that “until now I had known that Latin was a dead language. Now I know that it is the language of death.”

As well as describing Bulgarian funerary traditions (eat boiled wheat by someone’s grave, and you will dream about them), the novel also captures how technology has changed our relationship to death. “After death the phone is a source of metaphysical horror.” A few days after his father’s funeral, the late man’s mobile phone rings. A voice on the line says, “Hey Dinyo, hope you’re not sleeping…” We are told of a woman who buries her dead husband with his phone, only to have it ring her a few days later. “I was scared, then I decided to call him back and he didn’t answer.” The narrator, too, keeps almost accidentally calling his father before remembering.

There are some cliches, and the luxurious jetsetting of the narrator grows tiresome, but the occasional slip is easily forgiven in such a warm and melancholic writer – the kind who also remarks, “I wonder whether flowers aren’t covert assistants to the dead who lie beneath them, observing the world through the periscope of their stems”. The book is endlessly quotable, and the narrator’s travel bragging is put into an empathetic context by the lack of travel allowed to Bulgarians under the Soviet regime. He tells us of his father’s one trip abroad to Finland, a reward from his agricultural collective for good work. The amount that Bulgarians are allowed to spend there is limited by the Communist party. Another man on the trip smuggles extra spending money, hiding it in hand-rolled cigarettes. In a fit of excitement over finally getting to travel, he accidentally smokes it.

3 months ago

90

3 months ago

90