You’d be hard pressed to find a more alluring opening to a show than this: a bubbling pool consisting of 800kg of molten milk chocolate oozing seductively, filling the gallery with a sweet aroma and a soft, steady gurgling. On the walls brightly coloured, circular photographs of orchids, gerberas, sweet peas and chrysanthemums repeat the circular shape of the chocolate pool.

But for artist Helen Chadwick – whose Life Pleasures show at the Hepworth Wakefield is the largest retrospective of her work – pleasure is never that far from pain. It is not long before that thick, gloopy chocolate starts to smell sickly, the scent overwhelming the senses; the mechanism inside making the liquid bubble artificially. On closer inspection, the petals in the photographs are suspended in a variety of less pleasant liquids – industrial hand cleaner, window spray, washing up liquid – and the suggestive shapes of tonsils, testes and vaginas begin to emerge.

This push and pull – the delightful and the disgusting – is found throughout Chadwick’s practice. In Carcass, a huge, colourful column of rotting food taken from the Hepworth cafe fizzes and disintegrates; in Loop My Loop a glossy lock of hair is intertwined with a pig’s intestines; in Piss Flowers urine is used to create beautiful, organic blooms, and in Agape a glistening pair of tonsils glow through a lightbox to gory effect. The artist uses an unusual array of materials to elicit responses in her audience. She wants us to feel not think. She taps into our subconscious, into our feelings of desire, asking us to probe why a furry table or a pile of juicy worms simultaneously attracts and repels.

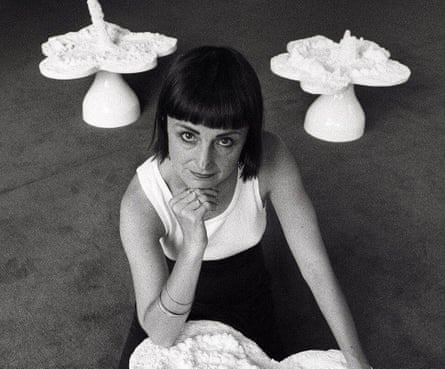

Chadwick’s MA degree show in 1977, In the Kitchen, bought her early acclaim and the images of women dressed as kitchen appliances still feel relevant. In the two subsequent decades, Chadwick was prolific, and despite her untimely death at 42, Life Pleasures is a celebration of a full and mature practice. The show categorises pieces under headings such as Feminism and Fetish, The Self as Subject and Landscapes of the Body to bring Chadwick’s interests to the fore. In the Kitchen and many other works in the exhibition often appear in “women artist” group shows, but Life Pleasures demonstrates the impact of Chadwick’s practice when seen as a whole and highlights her ability to take classical concepts, tip them sideways, inject humour and produce something relatable and enticing.

The autobiographical projects Chadwick produced aged 30, Ego Geometria Sum: the Labours, saw her create 10 sculptures from significant moments in her childhood and then take photographs of her carrying each sculpture. In the exhibition, the sculptures are in the centre of a space with the 10 photographs on pink walls, separated by long, shiny pink curtains. The photographs – the Labours – are named after the Greek myth in which Hercules was ordered to perform 12 perilous tasks and Chadwick completes her own tasks by lifting or holding her sculptures. This demonstrates strength but her contorted body also symbolises the way in which these moments from her past have shaped her.

The most impressive work is The Oval Court, originally made for Chadwick’s first major solo exhibition at the ICA in London in 1986. Across the floor is a low platform in a soft blue, covered in 12 photocopied images of her body as she folds around animals, food, fauna and an eclectic selection of objects. Five gold balls shimmer on the surface of the “ocean” of Chadwicks, and on the wall 11 columns drawn from St Peter’s Basilica are topped by Chadwick’s weeping face. The columns and the gold are regal, while Chadwick’s nude body gorging on food and wrapped up in random materials celebrates humanity enjoying earthly pleasures.

Opening at the same time is Caroline Walker’s Mothering, an exhibition that sits neatly alongside Life Pleasures, not least because mothering is almost the embodiment of pleasure and pain. But there are other satisfying links, such as Walker’s own self-portrait where – unlike Chadwick – she is not holding a childhood moment but a child who will shape her just as much. And like Chadwick, Walker is interested in the experience of women; she has spent many years painting women at work. Mothering captures her time spent observing a maternity unit at UCL hospital, London, and her own personal experiences.

Motherhood is exquisitely observed by Walker, who manages to document the quiet, dark shuffle of the sonography suite; the hazy, repetitiveness of night feeds; the coffee table clutter and half-consumed glasses of water that plague a new mother’s life. One of the largest pieces is Daphne, a painting of the artist’s daughter as a toddler captured through the lounge window. It is dusk and the exterior of the house has a blue hue, but inside the lounge is awash with warm, orange light and home comforts. Daphne stands silently, perhaps anticipating the return of her mother who is on the other side of the window. The two are separate for a moment – two individuals in a big world – but even unseen by Daphne, Walker is watching over her. Neither are ever truly alone.

In footage of Chadwick’s degree performance of Domestic Sanitation, the viewers are predominantly men. On today’s press trip it is entirely women, which hints at the success of work by artists such as Chadwick and Walker: if you allow women to be seen, if you focus on their desires, you make space for them to exist in the public consciousness.

-

Helen Chadwick: Life Pleasures and Caroline Walker: Mothering are at The Hepworth, Wakefield from 17 May until 27 October

10 hours ago

8

10 hours ago

8