In January, the comedian Ashley Bez posted an Instagram video of herself, trying to describe a heavy mood in the air. “How come everything feels all …?” she says, trailing off and grimacing exaggeratedly into the camera.

Digital anthropologist Rahaf Harfoush saw the video, and got it immediately.

“Welcome to the hypernormalization club,” Harfoush said in a response video. “I’m so sorry that you’re here.”

“Hypernormalization” is a heady, $10 word, but it captures the weird, dire atmosphere of the US in 2025.

First articulated in 2005 by scholar Alexei Yurchak to describe the civilian experience in Soviet Russia, hypernormalization describes life in a society where two main things are happening.

The first is people seeing that governing systems and institutions are broken. And the second is that, for reasons including a lack of effective leadership and an inability to imagine how to disrupt the status quo, people carry on with their lives as normal despite systemic dysfunction – give or take a heavy load of fear, dread, denial and dissociation.

“What you are feeling is the disconnect between seeing that systems are failing, that things aren’t working … and yet the institutions and the people in power just are, like, ignoring it and pretending everything is going to go on the way that it has,” Harfoush says in her video.

Within 48 hours, Harfoush’s video accrued millions of views. (It currently has slightly fewer than 9m.) It spread in “mom groups, friend chat circles, political subreddits, coupon communities, and even dog-walking groups”, Harfoush tells me, along with variations of: “Oh, so that’s what I’ve been feeling!” and “people tagging their friends with notes like: ‘We were just talking about this!’”

Why hypernormalization is relevant in the US

The increasing instability of the US’s democratic norms has prompted these references to hypernormalization.

Donald Trump is dismantling government checks and balances in an apparent advance toward a “unitary executive” doctrine that would grant him near-unlimited authority, driving the US toward autocracy. Billionaire tech moguls like Elon Musk are helping the government consolidate power and aggressively reduce the federal workforce. Institutions like the National Institutes of Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Food and Drug Administration, which help keep Americans healthy and informed, are being haphazardly diminished.

Globally, once-in-a-lifetime climate disasters, war and the lingering trauma of Covid continue to unfold, while an explosion of generative AI threatens to destabilize how people think, make a living and relate to each other.

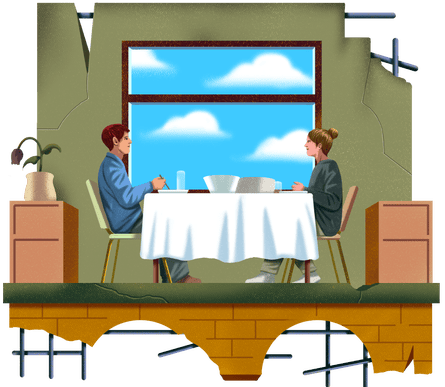

For many in the US, Trump 2.0 is having a devastating effect on daily life. For others, the routines of life continue, albeit threaded with mind-altering horrors: scrolling past an AI-generated cartoon of Ice officers arresting immigrants before dinner, or hearing about starving Palestinian families while on a school run.

Hypernormalization captures this juxtaposition of the dysfunctional and mundane.

It’s “the visceral sense of waking up in an alternate timeline with a deep, bodily knowing that something isn’t right – but having no clear idea how to fix it”, Harfoush tells me. “It’s reading an article about childhood hunger and genocide, only to scroll down to a carefree listicle highlighting the best-dressed celebrities or a whimsical quiz about: ‘What Pop-Tart are you?’”

In his 2016 documentary HyperNormalisation, the British film-maker Adam Curtis argued that Yurchak’s critique of late-Soviet life applies neatly to the west’s decades-long slide into authoritarianism, something more Americans are now confronting head-on.

“Donald Trump is not something new,” Curtis tells me, calling him “the final pantomime product” of the US government, where the powerful are abandoning any pretense of common, inclusive ideals and instead using their positions to settle scores, reward loyalty and hollow out institutions for personal or political gains.

Trump’s US is “just like Yeltsin in Russia in the 1990s – promising a new kind of democracy, but in reality allowing the oligarchs to loot and distort the society”, says Curtis.

Why the concept of hypernormalization is useful

Witnessing large-scale systems slowly unravel in real time can be profoundly surreal and frightening. The hypernormalization framework offers a way to understand what we’re feeling and why.

Harfoush created her video “to reassure others that they’re not alone” and that “they aren’t misinterpreting the situation or imagining things”. Understanding hypernormalization “made me feel less isolated”, she says. “It’s difficult to act when you’re uncertain if you’re perceiving reality clearly, but once you know the truth, you can channel that clarity into meaningful action and, ideally, drive positive change.”

Naming an experience can be a form of psychological relief. “The worst thing in the world is to feel that you’re the only one who feels this way and that you are going quietly mad and everyone else is in denial,” says Caroline Hickman, a psychotherapist and instructor at the University of Bath specializing in climate anxiety. “That terrifies people. It traumatizes people.”

People who feel the “wrongness” of current conditions acutely may be experiencing some depression and anxiety, but those feelings can be quite rational – not a symptom of poor mental health, alarmism or a lack of proper perspective, Hickman says.

“What we’re really scared of is that the people in power have not got our back and they don’t give a shit about whether we survive or not,” she says.

Marielle Greguski, 32, a New York City-based retail worker and content creator, posted about everyday life feeling “inconsequential” in the face of political crisis. Greguski says the outcome of the 2024 election reminded her that she lives in a “bubble” of progressive values, and that “there’s the other half of people that are not feeling the same energy and frustration and fear”.

To Greguski, the US’s failings are not only partisan but moral – like the racism and bigotry that Trump’s second term has brought out of the shadows and into policy.

Greguski is currently planning a wedding. It’s hard to compartmentalize “constant cruelty, things that don’t make sense”, she says. “Sometimes I’ll be like: ‘I have to put aside X amount of money for the wedding next year,’ and then I’m like: ‘Will this country exist as we know it next year?’ It really is crazy.”

The effects of hypernormalization

Confronting systemic collapse can be so disorienting, overwhelming and even humiliating, that many tune it out or find themselves in a state of freeze.

Greguski likens this feeling to sleep paralysis: “basically a waking nightmare where you’re like: ‘I’m here, I’m aware, but I’m so scared and I can’t move.’”

In his 1955 book They Thought They Were Free: The Germans, 1933–45, journalist Milton Mayer described a similar state of freeze in German citizens during the rise of the Nazi party: “You don’t want to act, or even talk, alone; you don’t want to ‘go out of your way to make trouble.’ Why not? – Well, you are not in the habit of doing it. And it is not just fear, fear of standing alone, that restrains you; it is also genuine uncertainty.”

“People don’t shut down because they don’t feel anything,” says Hickman. “They shut down because they feel too much.” Understanding this overwhelm is an important first step in resisting inaction – it helps us see fear as a trap.

Curtis points out that governments may intentionally keep their citizens in a vulnerable state of dread and confusion as “a brilliant way of managing a highly febrile and anxious society”, he says.

When we feel powerless in the face of bigger problems, we “turn to the only thing that we do have the power over, to try and change for the better”, says Curtis – meaning, typically, ourselves. Anxiety and fear can trap us, leading us to spend more time trying to feel better in small, personal ways, like entertainment and self-care, and less time on activism and community engagement.

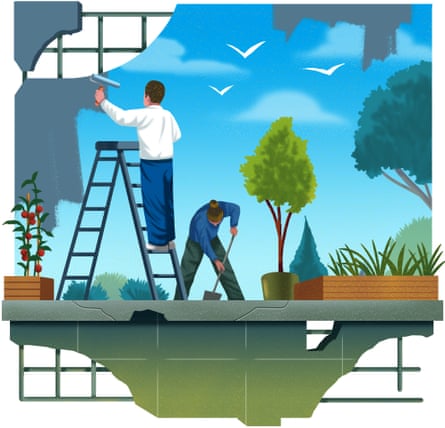

How to overcome hypernormalization

Progressive commentators have urgently called for moral clarity and mobilization in response to changes like the cuts to USAID funding, which has resulted in an estimated 103 deaths per hour across the globe; the dismantling of the CDC; and Robert F Kennedy’s campaign against vaccine science.

“Where is the outrage?” asks the Nation’s Gregg Gonsalves. “Too many lives are at stake to rest in this bizarre moment of frozen agitation.”

“I don’t know if there’s a massive shift toward racism as much as an expanded indifference toward it,” the historian Robin DG Kelley said in a February interview with New York Magazine. “People are just kind of like: ‘Well, what can we do?’”

Experts say action can break the spell. “Being active politically, in whatever way, I think helps reduce apocalyptic gloom,” says Betsy Hartmann, an activist, scholar and author of The America Syndrome, which explores the importance of resisting apocalyptic thinking.

Greguski and a co-worker have been helping distribute multilingual information about legal rights and helpline numbers, to be used in the event of Ice raids.

“It’s easy to feel like: ‘Oh, I’m in community because I’m on TikTok,’” she says. But genuine community is about “getting outside and talking to your neighbor and knowing that there’s someone out there that can help you if something really bad goes down,” she says.

“You’re actually out there talking to people, working with people and realizing there are so many good people in the world, too, and maybe feeling less isolated than before,” says Hartmann.

“But I also think we need a broader vision,” Hartmann notes. She suggests looking to resistance efforts against authoritarianism in countries like Turkey, Hungary and India. “How might we be in international solidarity? What lessons can we learn in terms of rebuilding sophisticated, complex government infrastructure that’s been hacked away at by people like Elon Musk and his minions in a more socially just and sustainable way?”

“We are in a period now when it’s absolutely essential to protest,” says Hartmann, citing the Harvard professor Erica Chenoweth, who argues that just 3.5% of a population engaging in peaceful protest can hold back authoritarian movements.

What makes dysfunction so dangerous is that we might simply learn to live with it. But understanding hypernormalization gives us language – and permission – to recognize when systems are failing, and clarifies the risk of not taking action when we can.

In 2014, Ursula Le Guin accepted the National Book Foundation’s Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters, saying: “We live in capitalism. Its power seems inescapable. So did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings. Resistance and change often begin in art, and very often in our art, the art of words.”

Harfoush reflects on this quote often. It underscores the fact that “this world we’ve created is ultimately a choice”, she says. “It doesn’t have to be like this.”

We have the research, technologies and wisdom to create better, more sustainable systems.

“But meaningful change requires collective awakening and decisive action,” says Harfoush. “And we need to start now.”

3 months ago

152

3 months ago

152