Some time in the winter of 1925-1926, the French author André Breton and his comrades Yves Tanguy, Jacques Prévert and Marcel Duchamp invented an old-fashioned parlour game. You write a word on a piece of paper, then fold it over so the next person can’t see what you’ve written, and you end up with a strange sentence. The game is now known as Exquisite Corpse, after the result of their first go: Le cadavre exquis boira le vin nouveau (The exquisite corpse will drink the new wine).

Exquisite Corpse gave Breton so much joy because it summed up the essence of the surrealist school of art he was trying to articulate at the time. In his first 1924 manifesto, he told budding surrealists to put themselves in “as passive, or receptive, a state of mind” as they can and write quickly. Forget about talent, about subject, about perception or punctuation. Simply trust, he writes, “in the inexhaustible nature of the murmur”.

In the year of its centenary, the spirit of Breton’s Exquisite Corpse is not just un-dead but frantically rattling the lid of its coffin from the inside. Several modern artists are continuing the surrealist tradition by composing with found materials (words, images, objects), drawn from the accidental debris of the everyday, to make the unexpected.

For a recent show at Frith Street Gallery, the British artist Fiona Banner showed works made with discarded mannequin parts she’d found in an abandoned Topshop in north-west England. In a film, titled DISARM (Portrait), she has emblazoned words like “disarm” on arms, “obsolete” on soles, and “delegation” on legs. At first she thought of it as a concrete poem or a Breton-esque poème objet. Then she realised, she says, that “actually, it’s more liquid than concrete”.

For Banner, the power of Exquisite Corpse, “its radical space”, lies not in the finished sentence but on that fold. “I think to not understand is a very important space,” she says. “To be free of human logic.”

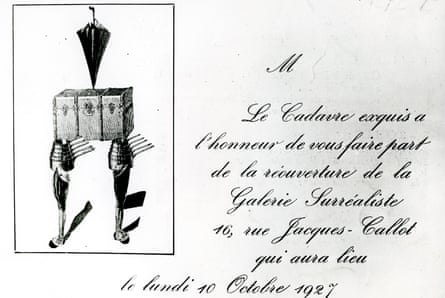

Dimitri Rataud, a French actor turned artist, whose work is now on show at HIS Paris gallery, makes what he calls “haikus marinières”: surrealist-inspired concrete poems he finds by blacking out most of the words on a ripped-out page of a random book. The name itself is a word play: the pieces look like Breton tops AKA marinières because of the stripes. And the poems (et soudain … le bonheur – “and suddenly … happiness”) are as light as a feather on the breeze.

The printed word, which he handles like a builder might a brick, is useful raw material. And each poem is but a moment. Rataud starts by tearing the cover off the book then opening it on the last page. He can never do the same thing twice. To his gallery’s dismay, he refuses to make copies.

Rataud is popular on Instagram, and you can of course see why: Breton tops, French romance, Japanese minimalism. And yet, these found poems are luminous, in the way they balance on that paper-thin edge between accident and intention. “I’ve found extremely beautiful haikus in sordid books.”

For the Paris surrealists of the 1920s – crawling out of the wreckage of the first world war – nonsense was a deadly serious matter. When the Centre Pompidou’s exhibition, Surréalisme (a touring mega-show currently at the Hamburger Kunsthalle), opened in September 2024, co-curator Marie Sarré described the centennial movement as one of the most politically engaged of the avant gardes. “Throughout its history, the political and the poetic ran in parallel,” she said. “It wasn’t an artistic movement or a formalism, but a collective adventure and a philosophy.” Contrary to other avant garde movements which embraced the notion of progress, it questioned everything. The surrealists were among the first anticolonialists, the staunchest anti-fascists, proponents of social revolution and proto-eco warriors.

“They asked the questions artists today are asking,” said Sarré.

To wit, Malaysian-born artist Heman Chong, whose work is currently on show at the Singapore Art Museum. This survey exhibition is organised into nine categories: words, whispers, ghosts, journeys, futures, findings, infrastructures, surfaces and endings. One piece, “This pavilion is strictly for community bonding activities only”, reproduces a sign Chong found in a communal space within one of Singapore’s Housing and Development Board block of flats. “The sentence itself is nuts, right?” he says. “That you would insist on community bonding activities, which means, literally, you cannot be there alone, right? Because you can’t bond with anyone alone.”

By contrast, he often makes installations with things people could secrete away – stacks of postcards; mountains of sentences from spy novels shredded on to the floor; a library of unread books. “I would love it if people just take things out of their own accord,” says Chong. “Coming from Singapore, which is an extremely paternalistic, authoritarian state, a lot of my work is not about telling people what they cannot do.”

In November 2024, South Africa-based Nhlanhla Mahlangu, who is a long-term collaborator of William Kentridge, gave a performance lecture titled Chant for Disinheriting Apartheid. It collates several spoken word compositions and improvised works, which delve into the brutal flattening of colonial oppression: language stolen, names mangled, bodies which have learned to recognise different guns by the sounds they make.

In one section, he performs, one by one, various unrelated sentences in the languages of isiZulu, Sesotho, Xitsonga, Venda, Xhosa. And then, “the language of apartheid”. He stands stock still, in total silence, for two whole minutes.

He recounts doing a workshop with children from Hillbrow, a part of inner Johannesburg beset by high crime and intense poverty. They were working on a performance of Aimé Césaire’s 1939 masterwork, Return to My Native Land – a gut punch of a poem against colonialism, which Breton called “the greatest lyrical monument of this time”. Mahlangu’s students, who were witnessing crime and death and abandonment on the way to class, said: “We experience surrealisms every day. We don’t understand why people go to universities and study it. Our lives are surreal.”

“Surrealism offers ways to look awry at things,” says Patricia Allmer, an art historian at the Edinburgh College of Art. She recently co-curated The Traumatic Surreal at the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds. “Because you can’t encounter trauma head on, you have to find ways of seeing it, either as a distortion, through a distorting lens or from the side.” For Mahlangu, it is about “bringing fluidity to what seems stable, and understanding that stability can be a weakness. It’s constantly not answering the question, but questioning the answers, asking more questions.”

In the 21st century, we may have grown wary of “isms” in art. In a climate of constant technological and economic interruption, the promise of a transformative cultural revolution can feel suspicious; the most powerful movement in modern art, contended a recent article in the Art Newspaper, may be the art market itself. But it’s worth remembering that when Breton first wrote about his ideas in 1924, he didn’t think of it as a manifesto, just a preface to a book of poems he wanted to publish. And that’s why Exquisite Corpse sums up surrealism’s most lasting legacy to modern art today: a tool that taps you into something unexplored, a game for “pure young people who refuse to knuckle down”.

2 months ago

78

2 months ago

78