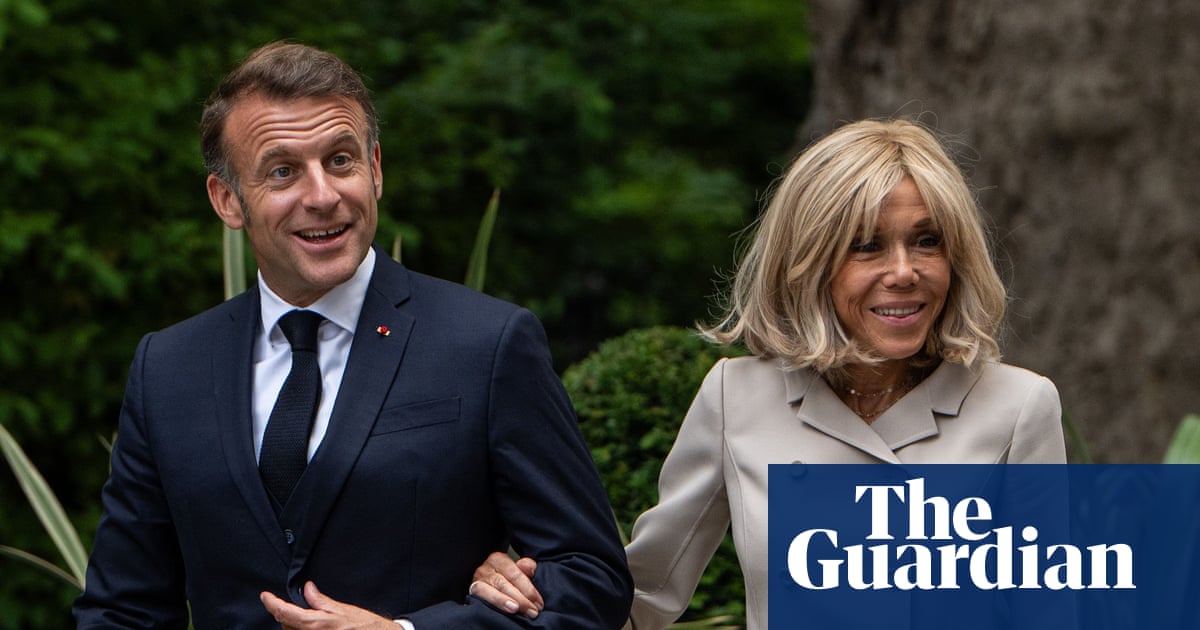

Within days of Russia launching its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Olaf Scholz announced a Zeitenwende, or historical “turning point”. The then German chancellor promised a security transformation by increasing defence spending, sending more aid to Ukraine, taking a tougher approach to authoritarian states and rapidly reducing Germany’s dependence on Russian energy.

It was a psychological turning point for a country haunted by its Nazi past but now expected to step up – as the biggest economic power in Europe – to a threat to the continent.

However, two years later, the German Council on Foreign Relations published a report saying Scholz’s transformation had yet “to deliver meaningful change”.

So with a new chancellor, can Zeitenwende be for real this time? There is no lack of action, or rhetoric. Since taking office three weeks ago, Friedrich Merz has vowed Germany will have the strongest conventional army in Europe, hosted the Ukrainian president, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, in Berlin and visited Kyiv, and attended the unveiling of German troops in Lithuania, the first permanent stationing of German troops on foreign soil since the second world war. Critically, he released the debt brake, so unleashing badly needed spending on the Bundeswehr, Germany’s military.

In his opening speech as chancellor he promised to provide all necessary financial resources for this. Germany’s allies expect this, Merz said in his government statement, “indeed, they practically demand it”. He announced his intention to transform Germany from a “dormant to a leading middle power”. He has already slipped easily into that role.

In Lithuania he said “the protection of Vilnius is the protection of Berlin. And our common freedom does not end at a geopolitical line – it ends where we stop defending it”. This from a country that as recently as 2011 saw its federal president resign under criticism for suggesting military action might be necessary in an emergency to “protect our interests”.

But not everything is going smoothly. On Monday, Merz had announced there were no longer any restrictions on the weapons supplied to Ukraine by Britain, France, Germany and the US, and that Ukraine could now do “long-range fire”. The implication was that Germany’s prized 500km-range Taurus missiles was to be finally made available, as indeed Merz had vowed while in opposition. This meant Moscow was vulnerable to these bunker-busting bombs, as were Crimea’s strategic bridges.

A response from Moscow was immediate. Sergei Lavrov, the Russian foreign minister, said: “To hear from the current German leader that Germany will regain its position as the leading military power in Europe just after we celebrated the 80th anniversary of the defeat of Hitler’s anniversary is quite symptomatic. History apparently teaches these people nothing.”

The former Russian president Dmitry Medvedev has reminded the world of the Nazi past of Merz’s father, and warned yet again of the threat of world war three.

The reality of what Merz is offering Ukraine is somewhat more complex, as is what he can do to meet Nato’s wider demands of an expanding German army.

The day after his “no limits” commitment he was forced to qualify his statement by saying this had been the case for a long time, and then prevaricating on whether he would meet his opposition pledge to supply Taurus. The strong suspicion is that the finance minister, Lars Klingbeil, of the Social Democratic party – Merz’s coalition partners – blocked Merz. The episode was reminiscent of the paralysis that disfigured the previous coalition government.

It may also be in office that Merz has been made more aware of complexities including the need for Ukrainians to have six months’ training on their use, and the implications of the German soldiers giving training inside Ukraine. The government has now retreated to a position of strategic ambiguity on what he will do, and focused on offering Ukraine a partnership to jointly build missiles.

Merz’s allies said the episode was not entirely futile. Thomas Röwekamp, of the Christian Democratic Union, who is chair of the Bundestag’s defence committee, told the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung newspaper that by rejecting range limitations, Merz had “removed one argument preventing the Taurus from being delivered”. This is not yet a “commitment” to the delivery of Taurus but the reason for the previous refusal had been “removed”.

The wider risk for Merz is that his rhetoric does not match the reality of what he can deliver, and rebuilding a German army after decades of neglect will take many years.

For instance in 2021, Germany agreed by 2030 to provide 10 brigades to Nato – units usually comprising about 5,000 troops. It currently has eight brigades and is building up the ninth in Lithuania to be ready from 2027.

Overall, it has approximately 182,000 soldiers serving in the force, plus, according to the defence minister, Boris Pistorius, 60,000 available reservists. By comparison, during the cold war up to 500,000 soldiers served in the Bundeswehr, which had access to about 800,000 reservists. By 2031, the number of active soldiers is to grow to 203,000.

Still, however long it takes, and whatever the missteps, Germany’s partners have already mentally adjusted to the return of Germany as the premier military force in Europe.

3 months ago

167

3 months ago

167