Last summer, Sonya*, aged 17 at the time, had endured more than two years of a difficult life under Russian occupation in the Kherson region of southern Ukraine. Her foster mother agreed that she needed a break.

Growing up under forced assimilation had been scary, Sonya says, and her Russian-controlled school had offered to take her to a holiday camp in Crimea, a balmy peninsula once famed for being the spa of the Soviet Union.

It was only after they had left that she discovered they were actually being taken to Volgograd, a city more than 600 miles (1,000km) away in the south-west of Russia. Far from being a holiday resort, the city is home to one of a growing number of state-run military-style training camps held for Ukrainian and Russian children.

Sonya spent a month at the Avangard camp, which has several other branches across Russia, and had sanctions imposed on it by the UK in November for its role in the forced deportation and brainwashing of Ukrainian children. She says she and other children faced a programme of activities that included being taught to dig trenches and rig them with booby traps and trip wires, load machine guns, take part in military-style formations and carry other children on their backs to simulate medical evacuations.

Similar to Soviet-era youth camps, these centres have escalated in number since the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Critics say they are used to indoctrinate children to prepare them for future service in the Russian military.

Now large numbers of children from occupied regions of Ukraine are reportedly being sent alongside the young Russians. The Kremlin portrays these facilities as physical and cultural learning opportunities for children.

“The instructors told me that with the certificate given after the training, you can join the Russian army, so I understood it wasn’t just play,” says Sonya. “I was so worried because I knew I would turn 18 soon and could be forced to sign up.”

After more than three years of war, thousands of Ukrainian children remain in Russia after being forcibly transferred or deported, while another 1.6 million are growing up under occupation, according to a report by GlobSec, a Bratislava-based thinktank.

Now, concerns are mounting that the children are being prepared for combat, with some already thought to be on the frontline.

“Forced conscription of foreign nationals is prohibited under international law, regardless of age, but Russia is naturalising these children as citizens to create a legal cover,” says Nathaniel Raymond, director of the Humanitarian Research Lab at Yale University’s school of public health, which documents civilian harm and human rights abuses across Ukraine.

The goal, says Raymond, is to “erase Ukrainian identity and make the children Russian. Russia has been running versions of this since 2014, scaling up after the full-scale invasion.”

Sonya and her family had to take Russian passports and other documents, and at school she had to study the Russian curriculum and language. Her younger brother was also sent to an Avangard camp, where she says he fell victim to the indoctrination.

“After being subjected to their propaganda, he took Russia’s side,” she says. “He says he will join the Russian army. He talks about it with his friends.”

Researchers at Yale have identified more than 100 camps, some military, others focused on indoctrination and many mixed. They are tailored to age and gender, and researchers have also tracked military vehicle training and shooting ranges using satellite imagery.

During their stay, children reportedly hear speeches from well-known propagandists and other figures involved in the invasion of Ukraine, learn to operate or assemble drones, and watch second world war re-enactments. Multimedia posted online by the camps show children in military-style clothing that feature the Russian flag and red armbands worn during combat in Ukraine.

after newsletter promotion

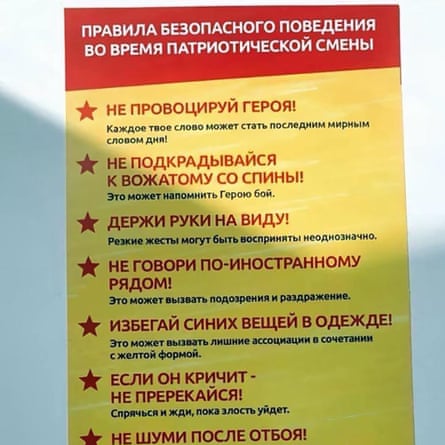

Camp rules circulating on social media suggest children are banned from speaking “foreign” languages, such as Ukrainian, and from wearing the yellow and blue colours of Ukraine’s flag. Contact with family is often limited.

Sonya says staff at her camp punished Ukrainian boys for disobedience by ordering them to strip to their underwear and perform intense physical exercise. She says they also often used a derogatory Russian term for Ukrainians.

Russia’s network of “military-patriotic” camps fits into a broader pattern of militarisation, say observers, with the state organising increasing numbers of programmes to prepare its own children for service, teaching them to wear bulletproof gear or design and test drones.

Ukrainian children in occupied territories are often given little choice about attending, says Megan Gittoes, from the GlobSec thinktank, with conditions at the camps for them frequently abusive – physically, mentally and psychologically. Gittoes says she has documented boys being forced to box each other or endure beatings.

“Children are forced into these programmes or their parents risk losing custody. It’s explicitly coercive. Ukrainian children face harsher indoctrination because their identity has to be erased. The aim is to instil fear, dependence on the state and loyalty to Russia,” she says.

Gittoes says it is hard to estimate how many children have been signed up to the Russian military. While there is a record of children who have fought for Russia and died since 2014, she says it is has been harder to track things since the full-scale invasion, as occupied areas are cut off and inaccessible.

“We know boys in Zaporizhzhia [a region partly occupied and claimed by Russia] have been told to submit passports for conscription. We have confirmed draft notices that have been sent out,” says Gittoes, who has also seen evidence of voluntary sign-ups.

“These people were Ukrainian and now they see themselves as Russian,” she says. “They are just proof Russia’s indoctrination policy works.”

Mykola Kuleba, head of the charity Save Ukraine, which helps rescue children from Russia, says they have returned an increasing number of young people who received draft notices.

In one case, they helped to return a Kherson teenager after he had served a year in the Russian army. He had been taken to Russia by his family, who were sympathetic to Moscow. He did not share their views, but when he was served a draft notice he feared he would be arrested if he did not go. He later managed to escape to an unoccupied area of Ukraine.

Kyiv insists that the return of abducted children is non-negotiable in any peace talks, but Moscow denies mass abductions and has dismissed the issue, reportedly offering to return only a token few.

After her stint in the military camp, Sonya, now 18, returned to her foster family in an occupied part of Kherson. Scared that she would be forced to return to the camp, she managed to escape earlier this year with the help of Save Ukraine to Kyiv. Her brother has stayed behind in Kherson.

* Name changed to protect her identity

2 months ago

49

2 months ago

49