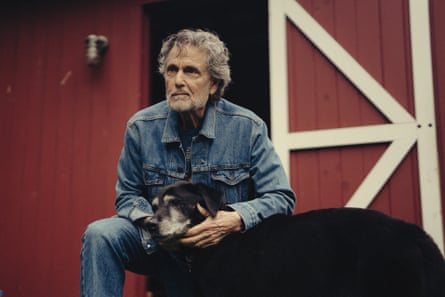

Chris Sarandon is doing great, thanks. The veteran actor looks extremely well for his 83 years, over Zoom from his home office in Connecticut, exuding warmth and geniality. More than once in our conversation – filled with digressions, anecdotes and impersonations – he talks about how he doesn’t take anything for granted.

“I occasionally do autograph conventions at Comic Cons,” he says. “And I was standing and talking to [fellow actor] Giancarlo Esposito. He said, ‘Well, how you doing?’ I said, ‘Giancarlo, look around you. There are thousands of people here just to see us and tell us they love us.’ If I said anything other than ‘I’m great’, just grab the nearest inanimate object and smack me with it.”

Sarandon is long retired from acting, he says, but “I have a beautiful home, and I live in … not splendour, but I have a huge garden. That’s my profession now: podcaster and gardener.”

More on the podcast later; Sarandon’s renown as an actor is built on a handful of classic movies, plus, as he’ll readily admit, a slew of middling to mediocre ones – not to mention a famous ex-wife who shares his surname. He had a golden run in the mid-80s and early 90s: teen horror Fright Night in 1985; fairytale classic The Princess Bride in 1987; and killer doll horror Child’s Play in 1989; and in 1993, providing the speaking voice for Jack Skellington in Tim Burton’s animated favourite The Nightmare Before Christmas.

These are the roles that bring him, and his fans, to the autograph conventions. The shelves behind him are filled with memorabilia, some official, much of it fan-made. “A gentleman last weekend, in Houston, Texas, walked up to me with his teenage daughter and his wife, and they handed me a little diorama that they had been up most of the night making with all their favourite characters of mine,” he says. “There were tiny little posters of all the movies around the background. I’m thrilled. I’ll put it up right behind me.”

Sarandon’s breakthrough was in a very different kind of classic movie, though: Sydney Lumet’s heist thriller Dog Day Afternoon, released 50 years ago in 1975 and based on a real-life incident just three years earlier – a Vietnam vet named John Wojtowicz (who becomes Sonny Wortzik in the movie, played by Al Pacino) held up a Brooklyn bank in what turned into a 14-hour hostage siege, which attracted a circus of police, media and onlookers – not all of them unsympathetic. Wojtowicz was married with two children but was reportedly raiding the bank to get money to pay for his lover’s gender reassignment.

Sarandon played the fictionalised lover, Leon Shermer, who is brought by police to the siege scene from a psychiatric hospital (after a suicide attempt) to try to talk Pacino down. Shermer makes a memorable impression: clutching the hospital robe, hair all a mess, vulnerable yet needy, having an almost mundane lovers’ tiff with Pacino over the phone from across the street. The performance earned Sarandon a best supporting actor Oscar nomination.

Dog Day Afternoon was one of the first Hollywood portrayals of gay and transgender characters, and to its credit, it treats their sexualities and gender identities as almost incidental. “That was the magic,” says Sarandon. “We saw these people as human beings, rather than: it’s about a gay couple, or a trans somebody. That certainly was what made it sensational for the public, but as far as we were concerned, what was important was where these two guys came from in their relationship.”

Sarandon did his homework. For research, he cooked dinner one night in his apartment for four “drag queens – people who dress in drag and live their lives as women” who a gay actor friend had introduced him to. “We sat around on the floor with our spaghetti, talking. Essentially, I was interested in their backstories.” One of them told him (he adopts a southern accent): “I went to see King Kong, and I looked up at Fay Wray and said, ‘I want to be her,’” he recalls. Another, he realised, he wasn’t seeing as a male in drag but as “a very attractive young woman, to the point where I was flirting with her. That was a real lesson in the dynamic of both the physiological and the emotional dimension of what happens to somebody when, like my character Leon says in the movie, ‘I felt like I was a woman trapped in a man’s body.’”

Ironically, for years after Dog Day Afternoon, Sarandon would get hit on by gay men at parties, he says. “But in a very aggressive way, because I was perceived as being ‘femme’. It didn’t disturb me in any way other than, ‘Oh my God, men can be pigs, regardless.’”

He would never be cast in such a role today, he acknowledges, “and rightfully so. It should be somebody who’s more authentically aligned with the character, but I’m very proud of it.” He deplores the way trans rights have become a political football in the US. “I proudly wear my Pride bracelet,” he says, holding up his wrist to the camera, “because this, to me is … it’s such a travesty.”

Becoming an actor seems to have been almost straightforward for Sarandon. He was born and grew up in a coal mining town in West Virginia, the son of Greek immigrants. His father came to the US in his 20s with nothing; his mother came from a Greek community in Florida. They ran a restaurant serving American cuisine, but spoke Greek at home. Later in life, he adds, his father left his mother and returned to Greece. She then moved to Los Angeles and became a nanny for Natalie Wood and Robert Wagner, then a companion to Rita Hayworth.

A college teacher persuaded him to try acting, and despite his initial reluctance, it became his ticket out of West Virginia – first, to the Catholic University of America, in Washington DC, where he did a master’s in theatre studies, and met his first wife, Susan. Then, via regional theatre, to New York, after a director suggested he audition for an agency. “I needed a scene partner, and so Susan read scenes with me, and we sang a couple of songs, I played the guitar, and they signed us both on the spot. Susan was still in college at this point.”

They married in 1967. He was 24 and she was 20. By the time Dog Day Afternoon came out, though, they had already separated. “We were both really young,” he explains. “I think we had, as everyone does, unreasonable expectations about what life could be like, and nor did we have any idea of what would happen to both of us in terms of our careers and our personal lives.” The separation was not acrimonious, he says. “In fact, we used the same lawyer for our divorce, but her life and my life just diverged.”

After they divorced in 1979, Susan had relationships with Louis Malle, David Bowie and Tim Robbins, among others. Chris married model Lisa Ann Cooper in 1980, and they had two daughters and a son before divorcing in 1989. He now lives with his third wife, actor Joanna Gleason, whom he married in 1994.

After Dog Day Afternoon, Sarandon had options: he was young, good-looking and Oscar-nominated – prime romantic lead material, you might have thought. But he didn’t go down that route. “Those are always the most boring roles, always,” he says. He much prefers the bad guys. “They do nasty things, and the audience can go, ‘Ooh, I wish I could do that.’” He may have taken it too far with his next role: in the 1976 movie Lipstick, he played Mariel Hemingway’s music teacher, who one day rapes her older sister, played by Hemingway’s real-life model sister Margaux. Lipstick was not a success (it killed Margaux’s acting career but launched Mariel’s). Its protracted rape scene, in particular, was criticised for being exploitative and voyeuristic. “But it was meant to be uncomfortable,” Sarandon says.

His next film fared little better: sub-Exorcist horror The Sentinel, directed by Michael Winner. “Michael Winner,” he groans. “Don’t get me started. I almost quit the business after that movie.” Sarandon found the British director to be unpleasant, even “malevolent” on set, he says. And again, the product was a flop. “That was one of those decisions when one thinks, ‘Oh, my name’s above the title and I’m being offered a ridiculous amount of money. And why not play a leading man?’ So what if, halfway through the movie, my face cracks and I’ve become a demon? Or whatever the plot was – I’ve repressed it at this point.”

The horror genre became his friend in the 80s, though: he found the right balance between bad guy and nice guy. In Fright Night, he is the vampire next door and every teenage boy’s nightmare: a sophisticated older man who seduces his girlfriend. But the movie is at heart a witty homage to classic horror cinema (writer director Tom Holland went on to cast him in Child’s Play). It was a similar story with The Princess Bride, a smart, affectionate spin on the classic fairytale fantasy, with Sarandon as the almost likable evil Prince Humperdinck.

He has particularly fond memories of Bride: improvising puns with Christopher Guest; introducing his young daughters to the legendary André the Giant (they ran away in terror. André said to him: “Either they run towards me or they run away from me”); director Rob Reiner and the cast singing doo-wop tunes on the set. Shooting in Sheffield, “the food was not great, so we did a lot of barbecuing. We would go into Rob’s room and sit around and play games, eat burgers and have a great time.”

The Princess Bride was not an instant hit but it went viral in a pre-internet kind of way. “A woman once walked up to me, held up a battered VHS and said, ‘I used to carry this around in my purse, so that whenever I’d go to visit a friend, I’d pull it out and say, have you seen this?’ She was an evangelist for the Princess Bride.” He also remembers the attorney general of Utah telling him that “every home in Utah owns a copy of The Princess Bride”.

What’s the appeal? “It’s not offensive in any way. There’s no sex in it, there’s very little violence, and its moral lesson is acceptable to just about everybody. But at the same time, it allows you to be both cynical and romantic.” It contains what’s billed as “the most passionate, most pure” kiss in history, he says, but also includes the line: “Life is pain … anyone who says differently is selling something.”

Life certainly became more painful for Sarandon from the mid-90s onwards. After The Nightmare Before Christmas, his career seemed to drop off, with guest roles in TV series (he’s played a lot of doctors), stage roles, minor movie roles, smaller independent films. “I call them mortgage movies,” he says. “I did a bunch of them, some of which I believed in, some I didn’t. Gotta work, gotta pay the rent.”

Sarandon went through “a major financial reversal” in the late 80s. “I invested money with a guy who defrauded me. I bought into a number of brownstone buildings in Manhattan when I was doing well, and the guy ended up being a fraud, and because I had signed all of the mortgages with this guy, I became as liable as he was, not criminally, but financially. So I lost everything. I’d been saving money all through my career for my old age, and I had to liquidate it.”

It was the worst time of his life, he says. He was broke, his marriage to Cooper was falling apart. Soon after, he landed a role in a Broadway musical that turned out to be a disaster: Nick & Nora, based on Dashiell Hammett’s The Thin Man, which was “just killed by the critics”. It closed after nine performances. One good thing came out of it, though: he met Gleason, who was also in the cast. Soon after, both penniless, they moved to Los Angeles, started working again and got married. “That was the beginning of my third life,” he says. “And now here I am.”

During the Covid lockdown he decided to start a food podcast, Cooking By Heart, in which he interviews guests about their lives and culinary memories. The roster has included chefs, writers and actors, including Cary Elwes, Stockard Channing, Rosanna Arquette and Brad Dourif. One day, he got a message on his Instagram from Susan. “She said, ‘Hi, your podcast looks great. Let’s do one.’” So she came to Connecticut and recorded an episode on stage with him. It was the first time they had seen each other in “maybe 15, 20 years” he says. “It really wasn’t so much an interview as it was, ‘Let’s talk about what’s been going on in our lives.’”

In the podcast, Susan is very kind about him: “When I met Chris, I thought, and correctly so, that he knew everything, because he took me to black-and-white movies and introduced me to literature and basically saved my life, actually, with his kindness.” Reconnecting with her was heartening, he says. “We’re in the last quarter of our lives, and we’ve gotten back together in terms of our friendship. Now we’re close friends again.”

The acting has pretty much dried up – “I get offered stuff occasionally, most of which I turn down because it’s not very interesting” – but he’s fine with that, he says. “Honestly, I don’t have the fire in my belly any more. There was a time early in my career where I was on fire, and I was thrilled to be doing what I was doing. I set out to have a career, I didn’t set out to be famous, and so my goals were fulfilled, really, sort of midway through.”

After that he was happy to be a “multidisciplinary” kind of actor. “I did it for a long time, and I was able to support myself – except for that disastrous three or four years when things were bleak. But I came out of it, and I did fine. I’m a lucky guy.”

3 months ago

94

3 months ago

94