All stories of addiction are grim and harrowing, but Patrick Dougher’s memoir reads like a picaresque comedy at times – albeit one laced with trauma and tragedy. There are hilarious tales of eccentric characters, like the great-aunt with enormous buttocks who killed his kitten by sitting on it: “That booty made all the decisions, and Aunt Cat, she just followed obediently.” And there are almost unbelievable episodes from Dougher’s life: his near-death experience in a crashing elevator, playing drums in Sade’s band, being stalked by a serial killer, finding a kilo of cocaine hidden inside a stolen table football machine. It almost sounds fun. And yet Dougher’s life is also a story of emotional damage, homelessness, self-destruction, loss and regret.

“The life of an addict, or at least my life, it is the full spectrum, it’s the polarities,” he says. “You can have incredible moments of exhilaration and joy and excitement, and it puts you in situations where you’re surrounded by unique characters, and then obviously the downside, which is pain and suffering and all of that stuff.” And yet, somehow, Dougher made it out the other side. “I would say I had a charmed life,” he says.

At one point he spent a month sleeping on a park bench; today he is a successful artist, speaking from a rented chateau outside Paris, where he lives with his partner and four-month-old daughter. He looks extremely well for someone who spent 20 years drinking, smoking and taking cocaine and whatever else he could get his hands on – he spent a whole year tripping on hallucinogens. His tattooed body looks remarkably well toned for a 61-year-old, and his mind is perfectly sharp. As with everything else about Dougher, the explanation for his condition is contradictory. “I would put anything you gave me into my system if you told me it would get me high,” he says. “If you said, ‘I got this white powder here, check this out,’ I would do it and not think twice about it. I would drink leftover drinks with cigarette butts in them. But I wouldn’t eat pork, or I went long periods where I was vegetarian, very mindful of diet. Even when I lived on the park bench, I would do push-ups.”

Dougher became an addict through “a combination of nature and nurture,” he says. It was in his genes, he suggests, that he “didn’t have an off switch”. His father was Irish, hence the name; his mother is African American, “which I always say is the perfect ethnic cocktail for an alcoholic addict.”

Dougher’s father was an alcoholic and so was his grandfather – but the root causes of their troubles were as much to do with socioeconomic circumstances and inherited trauma as genetics. When Dougher was a boy, his father told him one drunken evening how he had witnessed his father, Dougher’s grandfather, shoot himself. When Dougher was 13, his father decided to get sober, and became a kind, loving dad. A year later he died of a heart attack. On the way to the funeral, one of his father’s old friends took Dougher aside and told him that his grandfather, who was violent and abusive, had not really shot himself; his father had killed him, and had then married his mother “to punish himself.” His father was 22 when he met his mother; she was 19, and already a mother of two. After the funeral, Dougher poured himself a drink. “I got drunk,” he says. “That drunk lasted 20 years.”

New York, and especially Brooklyn, was a very different place in the 1970s and 80s. Today it is an expensive middle-class enclave; back then it was a run-down, working-class neighbourhood. Today it is economically segregated; back then it was ethnically segregated. “You could literally walk one block in the wrong direction and be in a neighbourhood where you weren’t welcome,” Dougher recalls. “The Italians, the Irish, the Jewish, they had their own internal racisms and pecking orders, but they were very united against anyone that was Black or Puerto Rican.”

As a mixed-race child, Dougher would be picked on and called “White Boy” by the Black kids, but he would also be attacked by the white Irish American kids. During one beating, he recalls, “I said, ‘Hey, I’m half-Irish,’ hoping that they would see me as something other than a Black kid that they hated so badly. And when I said that, the beating escalated – they really got angry. It was a clear reminder to me that the world is only going to see me as a Black person.”

Soon after his father died, Dougher dropped out of high school, moved into his mother’s basement and started effectively fending for himself – dumpster diving to find food, doing small-time jobs for money, which evolved into burgling neighbours’ houses, drinking, listening to music, smoking weed, selling weed. “They say weed is a gateway drug; I think it’s a gateway only for those who were heading through the gate anyway,” he says.

By his early 20s, as well as drinking heavily, he got into cocaine. It reached the stage where he was basically always on something – all of which required more money, more crimes, and a gradual disintegration of his life. “I worked, stole, borrowed and begged just to stay high,” he says.

When he was 21 he got into psychedelics, in particular a synthetic form of mescaline known as “microdots”. “It was like LSD mixed with amphetamine,” he says. “You can just kind of keep moving, so you’ve got the buzz, the energy of someone on meth, and then the trippiness of somebody who’s doing acid.” He took it every day for the best part of a year – one long acid trip, punctuated by moments of lucidity. “I marvel over the fact that I have any brain cells left,” he says. Does he remember anything about it? “Well, I ended up with a son at the end of that year.”

And yet, Dougher was also surprisingly active during this time. He took care of his son, Omari, on weekends. He had relationships – even at his least together, Dougher was always a fashionable dresser and a bit of a charmer, it seems. And he was always into music, not just the emerging local hip-hop scene (he was a terrible MC, he admits), but also reggae, and British rock like the Beatles and the Rolling Stones – “white boy music” – which led him to punk and new wave. He dressed like a punk, he says, in ripped skinny jeans and T-shirts held together with safety pins. He would go into Manhattan to classic venues like the Mudd Club and CBGBs to see bands like Bad Brains and Minor Threat. And to sell weed to white kids.

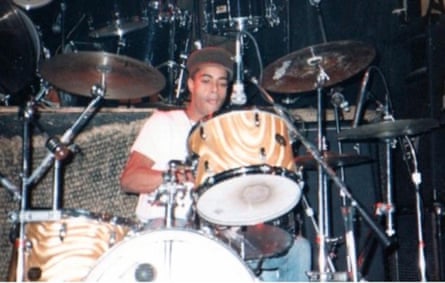

On his 17th birthday a girlfriend gave him a drum kit, and he took to it, forming a reggae band, then playing in bands for decades. In 2003, for example, he played drums on the cult stoner album Dub Side of the Moon (exactly as it suggests, it’s a dub cover version of Pink Floyd’s entire Dark Side of the Moon album). “I got paid $600 and I got two CDs. That was it.”

One time in 1992, a British guy approached him in New York and asked him if he would fill in for Sade’s drummer, who was stuck in England because of visa problems. They played one song, in a studio, for a Top of the Pops broadcast. He was utterly smitten with Sade, he says. “I really wish I had dated her.” She liked him too, evidently. She invited Dougher to play with them for the rest of their US tour. Call them the next day, she said. It was a dream come true. He got high to celebrate. Then he wondered if he would be able to keep on getting high if he was on the road. He never called back.

He somehow avoided the crack epidemic that ravaged so many Black and brown communities in the 80s. He says his older brother overdosed, and that his cousin, also an addict, “got thrown out of a moving car”. The fact that he is still alive is as much down to luck as anything else, he admits. “There’s so many moments where I could have died or ended up in jail or just been disabled, and so many folks that have had the same opportunities as me and just haven’t made it.”

And all along the way, there were many times when he tried to get sober, but just couldn’t. “Every addict and alcoholic, at some point, realises that this thing is killing them or ruining their lives, but they negotiate with it. They make deals like, ‘I’m going to figure it out. I’ll cut back. I’ll try a different drug. I’ll try a different alcohol.’ It took 20-odd years of daily use for me to surrender to the fact that none of that negotiation ever works, at least not for long.” Penniless, unemployable and alcohol dependent, he became homeless. After that month on the park bench, a friend let him sleep on the floor of his recording studio. He realised he had nothing.

When he finally quit, it was almost a non-event, it seems. “Nothing particularly tragic happened that day. But you get sick and tired of being sick and tired,” he says. He describes it as a moment of “grace”: “I came to this moment where I realised it was black and white: I could continue living the way I was, with active addiction and alcoholism, and die miserably, and die lonely, and die as a burden to those around me. Or I could face this demon and gather the courage to try to imagine a life free of alcohol and drugs.”

One of the most pernicious aspects of addiction, he says, is “this idea like, ‘I’m alone. Nobody understands me, nobody’s going to help me.’” It is not true, he says. “I wasn’t able to break out of it until I was willing to ask for help.” Like his father did at the same age, he started going to Alcoholics Anonymous meetings and began to change his ways and rebuild his life. It wasn’t easy, he says. “At 38 years old, I really had the emotional intelligence and coping skills of a 15-year-old.” He had never had a bank account or a driving licence. He had also never dealt with what he now sees as his angst, his anger, his lack of self-worth, his grief – all of which began with his father’s death. One of his first sober jobs was as a counsellor to troubled teenagers. “They’re incredibly sensitive and insecure and I identified with them, because I recognised that.”

He began to mend fences and rebuild relationships, including with his son, Omari, whom Dougher now describes as “my best friend”.

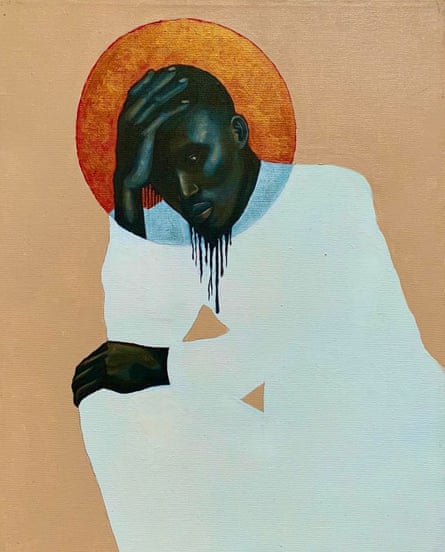

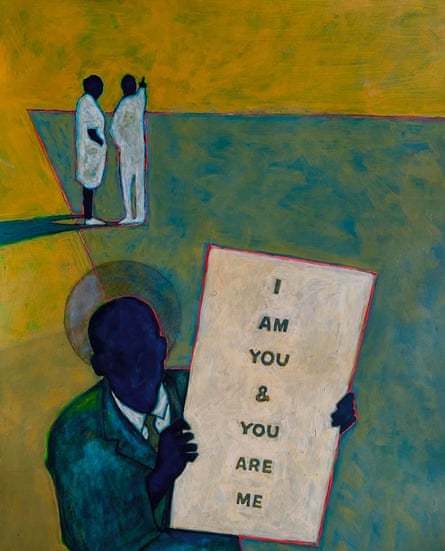

He became an art teacher and an art therapist, working with HIV positive children and community groups. And steadily he became an artist himself. “I was making art the whole time, but I never considered myself an artist,” he says. “It took me a few years of being sober to clean up my mind enough to get some direction and make the leap to realise, like, maybe all along I’ve been a creative and an artist.” His paintings often incorporate African American history and spirituality: often depicting Black figures with golden haloes, almost like religious iconography.

Dougher was always a spiritual seeker. Throughout his memoir he hangs out with numerous religious groups: Jehovah’s Witnesses; Black, Muslim Five Percenters; Rastafarians, even Hare Krishnas (admittedly the free food and the music were the main appeal there). That hunger is part of what drew him to drugs in the first place, he realises now. “It was a shortcut to God, in a sense, or what I thought was God.” He still sees his life and his work in a spiritual context, “this idea that there’s something bigger than me, and yet I’m still part of that big thing.”

As such, he is philosophical about how his life has panned out. “It makes you realise everything had to happen as it did. Obviously my life would have been completely different had I continued to play with Sade,” he laughs. “And there were so many times where I made the wrong turn, or in the moment that decision caused me more grief and suffering, but I kind of had to go through it to get where I ended up.”

He spends a few months in France every year with his new partner, 31-year-old Sélène Saint Aimé, a French-Caribbean bassist. The rest of the time he’s working in his Brooklyn studio. He’s happier than he’s ever been, he says. “I’ve been given a second chance at life. It’s the best way I could put it.”

7 hours ago

6

7 hours ago

6