Yvonne Hughes was 19, and attending the funeral of a friend with cystic fibrosis, when she realised: “Oh shit, I’m going to die of this.” She had met him during shared hospital stays in childhood, and although Hughes had always known she had CF, she had never understood her illness as terminal until that day in 1992, when she stood at the back of the crowded chapel in Glasgow. For three days afterwards, she couldn’t stop crying. “I had a kind of meltdown. That’s probably the first time I thought that this thing I had was going to kill me.”

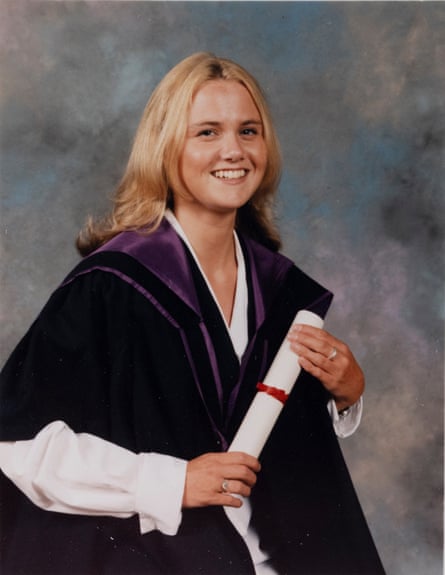

Over the next few months, Hughes, who was studying at the University of Glasgow, listened to her mum, dad and older sister chatting during family meals as if she was a ghost at the table. “I pulled back from them. I deliberately didn’t talk or include myself,” she says. “I wanted them to get used to sitting and chatting without me, so that when I died, they wouldn’t notice I wasn’t there.”

It’s a harrowing responsibility for a teenager to take, but self-erasure must have felt like a way to pre-empt death, perhaps to resist it. When she was growing up, cystic fibrosis was considered “a childhood disease” – because about half of those diagnosed did not survive their teens. A genetic condition in which the body creates thick, sticky mucus, it makes digestion difficult, damages lung function and can lead to respiratory failure. It affects about 160,000 people globally.

Now 52, and enjoying what she calls a “second chance” at life more than 30 years later, Hughes has emerged as a comedian. We are speaking on a video call before her one-hour show, Absolutely Riddled, which she is performing at the Edinburgh fringe, based on her experiences of living with the condition. “I want to be true to myself and my story,” she says. Why does she think she survived when so many didn’t?

For most of her childhood, Hughes, who works as a community development worker in Renfrewshire, didn’t regard herself as struggling for survival. Her parents didn’t sit her down in childhood to explain her illness; she had been diagnosed at six weeks old. But there were hospital visits and tablets and eating often made her vomit. Gradually, she says, she “put together those two words, cystic and fibrosis, with something that I had”.

At school, she kept her illness hidden, taking her medication at home. She was popular; joined the Brownies, then Guides. “I’m a very level-headed person, but I keep a lot in my mind. I remember when I was younger thinking: ‘There’s no point telling people about this because everyone is dealing with something. I’m nothing special.’ I just got on with it.”

Roughly one in every 2,500 people are born with cystic fibrosis in the UK, Australia and the US. Hughes’s older sister does not have the illness and the family had no idea what it meant for their lives, or for Hughes herself.

Only as she grew older did Hughes build a sense of the precariousness of her life. “My mum said to me: ‘We thought you were going to die, every day. We just didn’t know.’ It became their new normal to keep me alive.”

If she got a chest infection, pleurisy or pneumonia, she would go into hospital, and over the years made friends on the CF ward, a fragile community. When the curtains were closed around a bed for a long time, Hughes and the other children knew not to go past. She reasoned with herself, to allay her fears: “People were dying around me but I put it down to: ‘Maybe they had a really bad infection, maybe they were worse than me.’” In childhood, she developed “a lot of level-headed thought processes around why those people died”.

She found solace in the Cystic Fibrosis Trust magazine, and dreamed of attending one of the advertised camps. “Luckily, I didn’t,” she says, because in the early 1990s, scientists discovered that the camps were a hotbed for the spread of bacteria, present in the lungs and phlegm of children with CF. Many cross-infected each other, some with fatal consequences.

Did Hughes struggle to accept that sense of herself, as both vulnerable and a threat? “Absolutely,” she says. Hospitals implemented a policy of segregation, according to bacteria carried. Hughes has the pseudomonas bacteria, and after her friend’s funeral in 1992, she stopped seeing people with cystic fibrosis in case they had different bacteria or bugs that might lead to cross-infection.

She has stayed in touch by phone with one old friend. “We shared growing up in the hospital ward and I do love speaking to him.” But after that funeral, “I became reckless,” she says. “I thought: ‘Well, life’s for living. I’m just going to do what I want.’ I didn’t care very much for myself. I thought: ‘What’s the point?’ I spiralled.”

Her 20s and 30s passed in a blur of “festivals, partying, travelling when I could, flying by the seat of my pants … ” She had hoped to meet someone, and to have children. “I thought it would happen. And it never did.” In her 30s, her lung function got so low – 45%, then 36% – that she wouldn’t have been able to sustain a pregnancy anyway. “That was something I tried to grieve. But over the course of a year, I thought: ‘I’d rather be alive.’ My mantra became: ‘I’d rather have a full and short life than a long and unhappy one.’ These kinds of philosophical things got me through.”

Hughes doesn’t have a mantra now – “other than trying to be funny”. The frequency of her performances range from three times a week to every few weeks, depending on her health needs. But even in her reckless phase, she embodied a stoicism, too. She worked throughout – at a call centre, a radio station, the CF Trust. “I just had to keep going, pay my bills and mortgage.”

Did she ever wonder: “Why me?” She has had years of spitting out and swallowing mucus – “constant, constant” – hankies everywhere, non-stop sterilising of stuff, endless medication and pain, unable to take the next breath for granted. As a child, when she went into hospital, there was a faint sense of privilege at being given Lucozade and new slippers, things her sister didn’t get. But no one else in her family has the illness. Didn’t she feel aggrieved?

“It’s a difficult question,” she says. “I’ve thought about ‘Why me?’ in a positive sense – that it was me because I could handle it. Or, I’m glad … because this has made me the way I am.” She has also thought, “Why at all? Why did cystic fibrosis come into being? Why have this weird disease that just kind of ruins lives?”

While Hughes survived childhood by reminding herself that she wasn’t special, the differences between her life and others’ sharpened as she entered her 40s. She became an aunt, and bore close witness to her peers’ life transitions while she kept on being “just Yvonne – the one that never reached any potential”.

“I couldn’t have a career because I would always get ill. I never moved social class. I always remained working class.” Her dad was a welder, her mother a GP receptionist. “Everything I did, I did myself. But it was day by day, week by week. There was never a plan. I always felt I could never get ahead of myself.”

In 2018, aged 45, with deteriorating health, Hughes took redundancy from her job as public affairs officer at the CF Trust. Eating was difficult. Her weight hovered around 7 stone. She braced herself for the possibility of a lung transplant, but as her lung capacity dropped to 30%, she was deemed too ill for the waiting list. “I was like: ‘OK, that door’s closed. At this point, there isn’t anything else on the horizon to keep me alive.’” She completed an end-of-life form, and met the palliative care team. She thought: “I’ll see my days out with my parents, make memories and know I did well to get to 48.”

Then, in 2020, the UK government granted access to a new drug, Kaftrio. Hughes had read about its worldwide trials. When the delivery driver knocked on the door, she told him: “You’re going to save my life.” At that point, her lung function was down to 26%.

Within an hour or two of the first tablet, she started coughing. “They call it the purge,” she says. There was so much mucus – dark, watery and horribly fascinating – she captured it in a cup, put a lid on it, and stowed it in a drawer in her bedroom. “I kept that cup for a long time,” she says. Maybe she already knew it was a relic.

The Kaftrio turned Hughes’s life “a whole 180, literally overnight”. There are side-effects – insomnia, weight gain, which have brought other challenges – but before long, she says, “I could breathe again without coughing. I went back to work within the year. I could run, I could dance, I could speak, I could stand up straight and cook. I used to always be bent over, catching my breath. And then all of a sudden that was gone. It was a miracle.”

Energised, she decided to enrol in an evening course. Acrylic painting, maybe, or playing the keyboard? But at the University of Strathclyde’s Centre for Lifelong Learning, it was the flyer for comedy that caught her eye. “I had always loved going to gigs. Something clicked and I enrolled.”

She performed a five-minute set for the course finale – and immediately wanted to do it again. “I started applying for clubs, Monkey Barrel and the Stand Comedy Club [both in Edinburgh]. I got Red Raw [the Stand’s beginners’ slot] and went from there. I want to change my life,” she says, “and I am doing comedy to see if I can change my life.”

Nearly four years ago, Hughes met her partner, Alan, online. Having spent a lifetime feeling unable “to rely on a future”, she has had to learn to picture one – and to override her old instinct to absent herself to mitigate later losses. Sometimes, this means catching herself in the act of “pulling back” from Alan, and letting the pleasure she takes in his company teach her to quiet her mind.

Life now is so different, it requires a conscious effort to remember how hard it was from one moment to the next. “I used to breathe so shallowly that I had to take a – haa! – sharp intake of breath – to feel I was breathing,” she says. The sound punctuated even the simplest actions – after getting into a car, for instance, after reaching for her seatbelt, after pulling it across her, after fastening it.

“Now I can get in the car, pull the seatbelt over and go. I can walk and talk. I can laugh without wetting myself or going into a convulsion of coughing, pulling a muscle or breaking a rib,” she says. “It is a horrible, horrible disease. It suffocates you. It takes every inch of your breath away. And now it is something I can live with and not die from. I’ll probably live to get my pension.”

Comedy has brought “fun, joy and laughter” back into Hughes’s life. But it has also given her something that nothing else has. “I had never found anything for me in my life. I’d never married. I had no children. So I had no community. Nothing,” she says. “There were people getting their careers and their lives sorted. Comedy was the one thing that was for me. And it still is. Just for me.”

3 months ago

129

3 months ago

129