The Anthropocene is a new term used by scientists to describe our age. While scientific experts argue about the start date, many point to about 200 years ago, when the accelerated effects of human activity on the ecosphere were turbocharged by the Industrial Revolution. Our planet is said to have crossed into a new epoch: from the Holocene to the Anthropocene, the age of the human.

The strata of rock being created under our feet today will reveal the impact of human activity long after we are gone. Future geologists will find radioactive isotopes from nuclear-bomb tests, huge concentrations of plastics, the fallout from the burning of fossil fuels and vast deposits of cement used to build our cities. Meanwhile, a report by the World Wide Fund for Nature and the British Zoological Society shows an average decrease of 73% of wild animal populations on Earth over the past 50 years, as we push creatures and plants to extinction by removing their habitats.

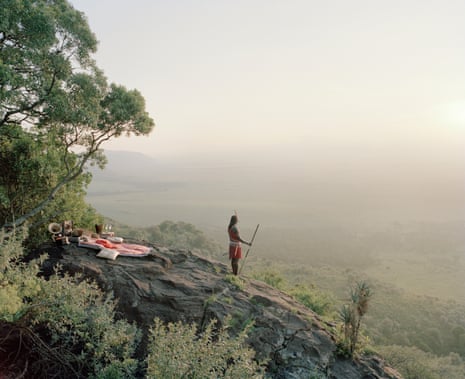

Humans have concentrated in cities. We have separated ourselves from the land we once roamed – and from other animals. But somewhere deep within, a desire for contact with nature remains. So, as we destroy the natural world around us, we have become masters of a stage-managed, artificial experience of nature, a reassuring spectacle, an illusion.

Over the past six years I have visited 14 countries across four continents, observing how we humans immerse ourselves in increasingly artificial landscapes. We holiday on synthetic beaches, attend zoos that display living animals in artistically rendered dioramas of their natural habitats, and visit amusement parks that offer a “jungle experience”. We gaze at aquatic creatures in artificially lit sea-worlds, and at polar bears in Chinese shopping malls, pacing out their existence in glazed enclosures of plastic ice and snow. We ski on artificial slopes in Dubai, while outside the desert temperature is 48C.

Tropical Islands holiday resort in Germany is a short train ride from Berlin. Housed in a vast hermetically sealed dome, the resort offers a sandy beach, a 10,000 sq metre indoor rainforest, a waterfall and a mangrove swamp with live turtles, dragonfish, flamingos and macaws. It’s so large you can ride in a hot air balloon inside the dome, hovering above the crowds on the synthetic beach below.

Walt Disney World in Florida covers more than 39 square miles (100 sq km), making it almost the same size as Paris. Completed in 1971, it is the largest and most visited theme park on the planet. In 2022, more than 47 million people visited Walt Disney World, where total revenue was $28.7bn. Nine million of those people visited Disney’s Animal Kingdom. It was here that I visited Disney’s version of Africa, where you can observe elephants, rhinos and fake villages (without leaving your electric mobility scooter with built-in cup holder). Experiences on offer include Kilimanjaro Safari and Gorilla Falls Exploration Trail, offering safe views of the world’s largest primates, set to music. At the Tusker House restaurant you encounter Donald Duck in a colonial-era safari suit and pith helmet, before setting off on the Wild Africa Trek to see the rhinos.

In the numerous theme parks and zoos I visited, I realised a strange thing: in these places, nothing happens. There are no surprises. There may be a wave machine, or a volcano that puffs smoke on the hour, or a rollercoaster offering momentary thrills. But nothing changes, good or bad. Everything repeats itself. Nothing happens unless it’s part of the show. Here, nature is made safe – no thorns, biting insects, flooding or unpredictable creatures. This is nature only as spectacle.

Even the surviving scraps of nature in the real world are becoming packaged for our consumption.

Yosemite national park in California receives more than 4 million visitors a year, almost all of whom arrive by car. I found myself in a long traffic jam of SUVs crawling through the park, engines and air-conditioning running. Occasionally, a window glides open and an arm extends out to take a photo on a smartphone.

Ski tourists are becoming more demanding, too. Everybody wants a winter wonderland, despite warming temperatures. According to the European Environment Agency, the length of snow seasons in the northern hemisphere has decreased by five days each decade since the 1970s. In Italy, 87% of ski slopes were kept operational with artificial snow in 2018, the first year I visited. Many ski resorts use artificial snow to extend their seasons, and some now rely almost entirely on artificial snow production.

I saw whole hillsides covered with snow guns working through the night. A typical resort I visited in the Italian Dolomites had a five-megawatt power station to run its 250 snow guns. The owner told me: “We make better snow than the natural stuff. In the past 20 years, the tourists have come to expect perfect-quality champagne snow.”

Hotels in Asia offer live penguin encounters in restaurants, while South African lion farms offer tourists the chance to pet lion cubs and walk with tame adult lions. Later these same animals will be sold to visiting trophy hunters who want an effortless experience of hunting in “the wild”. Even the great previously untamed places are under assault.

Just 3% of the world’s land now remains ecologically intact, with healthy populations of all its original animals and undisturbed habitat.

Charles Darwin controversially recategorised man as just another species – one twig on the grand tree of life. But modern humans are no longer just another species. We are the first to reshape the Earth’s ecosystem. We have become the masters of our planet and pivotal to the destiny of life on Earth. But it seems we are not prepared – ethically, emotionally or scientifically – for the enormous side-effects of our new and recklessly wielded power over our planet. In his 1989 book, The End of Nature, the writer Bill McKibben predicted a day when our changed environment would surpass the capacity of our environmental vocabulary. The remade Earth, he argued, would set record after record – hottest, coldest, driest – before people would be forced to seek new ways of describing and understanding events. For a long time, he suggested, confronted with evidence of a changing world, humans would simply refuse to change their minds.

Social media and the internet’s ceaseless flow of visual stimulation and information have birthed a state of unreality, where we are no longer looking for truth, but only a kind of amazement.

Our future as a species depends on urgent new evaluations of humanity’s relationship with the natural world. We have divorced ourselves from nature, yet we crave a connection with the very thing that we have turned our back on. In surrounding ourselves with simulated recreations of nature we create unwitting monuments to the very things that we have lost.

It will take a paradigm shift in our priorities and empathies to change. But it is on an industrial and political level that change needs to happen. We already have a list of great ideas: protected natural habitats, rewilding, sustainable agricultural practices, ethical treatment of animals, renewable energy, and reductions in greenhouse gas emissions and plastic pollution.

We know what can be done. We just need to find leaders and captains of industry who want to do it.

-

The Anthropocene Illusion, by Zed Nelson is published by Guest Editions

3 months ago

110

3 months ago

110