Half a century later, Richard Dreyfuss still won’t go in the water. “I have never done it, not since the film,” the Oscar-winning actor says, “because you’re totally aware of what you’re not aware of and you’re not aware of anything underneath.”

The film is Jaws, whose release 50 years ago on 20 June marked a turning point in both the history of cinema and public perception of sharks. It was the movie that in effect invented the summer blockbuster, paving the way for Star Wars, Jurassic Park and the Marvel Cinematic Universe. It cast sharks in the role of monsters to be feared and killed – but also stimulated interest in marine conservation.

Based on a novel by Peter Benchley and directed by Steven Spielberg, Jaws tells the story of a great white shark terrorising the beach town of Amity Island, prompting police chief Martin Brody, marine biologist Matt Hooper and grizzled fisherman Quint to hunt it down. It earned rave reviews from critics and became the first movie to take more than $100m in theatrical rentals.

The three men on a boat were Dreyfuss (Hooper), Roy Scheider (Brody) and Robert Shaw (Quint) and the dynamic between them is central to the film’s appeal. Today only Dreyfuss is left. Now, 77, sitting in a library at his home in San Diego, California, his memories remain lucid. “First of all, you have to remember this is not 50 years later,” he says via Zoom. “This is yesterday.”

At first Dreyfuss turned the part down. “At this lunch meeting he [Spielberg] illustrated the story very well, very vividly, and he said, did you like it? I said, oh, yes. He said, do you want to do it? I said, no, and he said, why? I said, because it’s going to be a bitch to shoot. I at that moment was not looking for difficulties. I turned him down in that meeting and then I turned him down again.”

But then Dreyfuss saw a rough cut of a film he had just made and thought his performance looked so bad that it might end his career. So he called Spielberg and begged him for the role. Once shooting got under way, it did not go as Dreyfuss had prophesied at that lunch meeting.

“One of the many things that I learned was that it was not a bitch to shoot at all. I would say that there was one word that characterised the shoot and that was waiting. More waiting than anything.”

Despite the difficulty and cost, Spielberg insisted on shooting in the open ocean off Martha’s Vineyard for the sake of authenticity. The budget ballooned from $4m to $9m. Production went 100 days over schedule and was plagued by the malfunctions of the mechanical shark (nicknamed “Bruce” after Spielberg’s lawyer).

At the mention of this, Dreyfuss puts his hands to his mouth to mimic a loudspeaker: “‘The shark is not working. The shark is not working. Repeat. The shark is not working.’ And then one day you hear this. ‘The shark is working! The shark is working!’”

He recalls: “There were three different sharks and three different crews that worked the shark and it was all a disaster. There’s a line in the film where Robert says he had these eyes, these doll’s eyes, and he did because they were doll’s eyes!

“Steven had to conceive of a film which implied the shark rather than show it directly. That was the story of the shoot: the director, Steven, had to rework his conception of the entire movie because he knew he could not show it as brazenly or blatantly as he had assumed. That ultimately made the film a masterpiece.”

Spielberg, who was in his mid-20s at the time, has credited director Alfred Hitchcock with influencing his less-is-more approach to building suspense. He also received a mighty lift from composer John Williams, whose two-note theme music initially seemed so simple that Spielberg thought it a joke until he realised its visceral menace.

Dreyfuss comments: “John is an extraordinary composer and it took him no time at all to create a sound picture that could carry the film. You don’t see the shark first: you hear it. Under the credits you hear bar-dum, bar-dum, bar-dum, bar-dum and you’re seeing that shark moving through the underbrush and I’m telling you, it put the fear of God in the audience and me and everybody.”

The British film critic Mark Kermode has argued that Jaws is not about a shark. A case in point is a scene below deck in which Quint recalls how sharks ravaged survivors after the wartime sinking of the USS Indianapolis, providing Quint with a powerful motivation for his hatred of the animals. Enhanced by improvisation captured on tape recorders, it has been described by Spielberg as “the scene that I’m proudest of in Jaws”.

Shaw – who struggled with alcoholism for most of his life – made himself drunk for the scene but it backfired on the first take, Dreyfuss recalls. “He lost control of himself and he was terribly embarrassed and that only made him drink more and so that day was a terrible humiliation for him. Because I was sitting next to him and in the shot, it was painful.

“That night he called Steven at two or three in the morning and said, how badly did I humiliate myself? Steven said, not fatally. He came in the next morning and he did the scene in one take and he was brilliant.”

For decades there have been stories that the palpable tension between Hooper and Quint was not based on acting alone but mirrored personal animosity between Dreyfuss and Shaw. The alleged feud was explored in the recent play The Shark is Broken co-written by and starring Shaw’s son Ian. Dreyfuss, however, is adamant this is a myth and one that pains him to this day.

“If you are aware of the stories in and around the filming, you know the ‘discovery’ of the feud between Robert and myself didn’t exist for 25 years,” he says firmly. “It was not the truth. It was not the fact of our relationship at all. Twenty-five years after the film was over, I found that there was this ‘feud’ between us.

“What there had been was one day where I was angry at him for stuff. It was one day. To a great extent what happened was that in order to jack up the stories about the film, they re-emphasized the story of this feud, which wasn’t real and the people who did it knew it. I resented that for a long time but Robert was already dead by 15 years and there was nothing I could do.

“I cherished his memory and what I was learning from him and I’m not kidding about that. Robert was an extraordinary actor and an extraordinary writer and I could tell you a great number of stories about all of that. But I won’t allow anyone to walk away from an interview with Richard Dreyfuss and think that there was reality to the feud.”

He and Shaw had even made plans for a future collaboration, Dreyfuss adds. “We were in the hold of the boat and we were both napping and all of a sudden Robert said, ‘I know. I’ll play the Ghost to your Hamlet if you play the Fool to my Lear.’ I said, ‘You’ve got it. But not for 10 years.’ He said, ‘Why?’ I said, ‘Because you’ll eat me alive,’ and he laughed and said, ‘OK.’

“So we had an agreement to make those two pieces and unfortunately he died very quickly. That was a catastrophic feeling, a loss that I knew had changed my future. I could have taken willing advantage of that friendship and I was unable to.”

When Dreyfuss first saw the finished cut of Jaws, it made a huge impression. He recalls: “I was as terrified as if I had never experienced the making of this film. I was completely swept up in the story. It was so much an achievement of film-making and my friend Steven, who’s sitting there – I knew that I was watching the crowning of the uncrowned prince of Hollywood.”

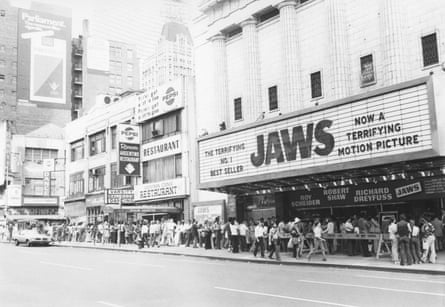

The movie drew long queues at cinemas and quickly became a cultural phenomenon. “There was, for the first time, an awareness of how a film could affect all of society. There was not one group, one country, one people who were immune to this. He happened upon something that was so ubiquitous and shared by all people. Wow! Although Steven did that a number of times afterwards in other films, it’s easy to spot because of Jaws.”

Dreyfuss has never again sat down to watch the whole of Jaws from start to finish, although if he chances on a TV showing that is already under way, he usually sticks with it to the end. And what of the three widely panned sequels? “They should never have been made and I have absolutely no interest in seeing them. Never have and never will.”

Dreyfuss, Shaw and Spielberg were not involved in Jaws 2, released in 1978, but it did star Scheider and Lorraine Gary, playing his wife Ellen Brody as she had in the first film. Gary is now 88 and living in Los Angeles. Speaking by phone, her memories of working with Scheider on Jaws are less than rosy.

“He was very much an isolated human at that point. He smoked; I hate cigarettes. He also spent a tremendous amount of time with one of those tin foil reflector pans, getting his tan. There was very little in common. Years later I was in New York and we ran into each other on Madison Avenue. We talked like real people at that point instead of actors on the set and it was fun – it was very professional.”

Typically summer months were quiet for cinemas but Jaws was deliberately timed for when people were at beach resorts and accompanied by the tagline: “See it before you go swimming!” The film opened on 464 screens in North America and was boosted by a major TV advertising campaign, still unusual at the time and marketing stunts such as themed ice-creams. Gottlieb once observed: “That notion of selling a picture as an event, as a phenomenon, as a destination, was born with that release.”

Did Gary have any sense that Jaws would be such a gamechanger? “Absolutely not. No clue. It stunned me when it did, what it did and it stuns me now. Every day I get fan mail. I’m an 88-year-old woman. Come on, leave me alone! It’s all very strange to me but luckily, it’s fun.”

Unlike Dreyfuss, the experience did not put her off swimming. Gary has gone scuba diving and come within five feet of a shark. “I’m not scared of sharks,” she says. “The only time I was scared by sharks was when I saw my sons and my grandchildren in the ocean and I thought, sooner or later there’ll be payback, but there wasn’t. I truly do not have a very strong feeling about hurting the reputation of sharks. They deserve to be known for who they are and what they do.”

The film’s impact on these ancient predators, which date back 450m years – longer than the dinosaurs – is complex and frequently debated. Its official trailer speaks of a “mindless eating machine” that will “attack and devour anything”, adding: “It is as if God created the devil and gave him jaws.”

Small wonder Jaws instilled widespread fear of sharks, whose population has fallen dramatically since the early 1970s. Spielberg told BBC Radio 4’s Desert Island Discs in 2022: “I truly and to this day regret the decimation of the shark population because of the book and the film. I really, truly regret that.”

But the film also sparked engagement in marine science and conservation, a legacy actively pursued by the author Benchley, who died in 2006, and his wife Wendy, who is executive producer of a Nat Geo documentary, Jaws@50: The Definitive Inside Story.

In a phone interview, Wendy, 84, comments: “Jaws tapped into an innate fear of being eaten by a monster. It was a scary book and a scary movie but 90% of the people who read the book or saw the movie got over their fear; 10% never went back in the water.”

Benchley had worked as a speechwriter for President Lyndon Johnson over the last two years of his presidency then wanted to get back to freelance writing. The couple were living in Pennington, New Jersey, with two young children and financial pressures but Benchley decided to try writing a book.

He had two ideas, Wendy says. “One was about current day pirates; one about a great white shark that hangs around a town and causes some mischief. I said, oh, honey, I don’t think either of these ideas are going to be that great. Thank heavens he didn’t listen to me.”

Benchley had spent childhood summers sailing, fishing or swimming at Nantucket Island, off the coast of Massachusetts, where the black dorsal fins of sharks could be seen above the surface. “Now, he knew after he wrote the book, and after people started to do more and more research on sharks, that sharks do not hang around. They don’t like human flesh: we’re too bony, we don’t have enough fat on us. Peter always said, ‘I would never write Jaws again because I now know how important this animal is and how magnificent it is.’”

Benchley was unsure what to call the book. Wendy says: “Some suggested titles were pretentious, like Leviathan Rising, and others were very scary, like White Death. Peter’s father, who was a wonderful guy and a novelist also, said with his good sense of humour: ‘How about What’s That Noshing on My Leg?’

“It was down to the wire and Peter said, let’s settle on the word Jaws because nobody knows what it means and nobody reads a first book anyway. There was absolutely no expectation that this would be rocketing up the New York Times bestseller list.”

Nor did the Benchleys expect it to become a movie. Spielberg had chanced upon galley proofs of the book and been enthralled. The rights were secured by producers Richard Zanuck and David Brown for $150,000, plus $25,000 for a first draft of the script, before the novel had been published (it would sell 5.5m copies before the film opened).

Wendy says: “I do remember when Peter got the phone call in our little house in Pennington. I cried. I thought, our life is ruined because I had known people who suddenly got some wealth and I thought, oh no, but we were a little bit older and we had good, strong families and we had wonderful friends and so our life stayed very solid.”

Benchley co-wrote the screenplay, and had a bit part on screen as a reporter, but was relieved when Carl Gottlieb took over the day-to-day writing, including a leavening of humour. The film version removed plot lines from the novel such as a mafia connection and an affair between Hooper and Brody’s wife. Spielberg also decided: you’re gonna need a bigger shark.

Dismayed by the demonisation of sharks, Benchley wrote, narrated and appeared in dozens of TV documentaries about marine life and became

a full-time marine conservationist. He and his wife worked for the Environmental Defense Fund. The Peter Benchley Ocean Awards are held each year to celebrate individual excellence in ocean conservation.

Wendy says: “We were horrified that people took this novel and this fictional movie as some kind of a licence to go out and kill sharks and to schedule more shark tournaments. We took this very seriously and began to work on conservation issues.”

As awareness has grown, she adds, applications to study marine science have risen at universities around the country. “That is an outcome of Jaws that people now understand. In fact the ocean community embraces Jaws as a positive for ocean science, ocean research and conservation.

“The other thing that surprised us and relieved us greatly was that Peter began to get thousands of letters from people all over the world who said it was a great book, scary movie, but it intrigued them and they want to know more about sharks. There were so many letters from people wanting to be Hooper, not in a white lab coat sitting doing research but out on the ocean and experiencing not only sharks but other ocean creatures. That was a wonderful feeling.”

3 months ago

109

3 months ago

109