“A pitiful land, flooded twice a day,” was the verdict of the Roman savant, Pliny the Elder, of a region where “wretched peoples living in huts” must battle perpetually to resolve the question of “whether this region belongs to the land or the sea”.

The Greek geographer Pytheas reckoned “more people die here in the struggle against water” than against men. Yet by the late 17th century, the Netherlands was arguably Europe’s wealthiest nation. Even today the Dutch are, per head, in the global top 10.

-

The artist and singer Floyd Brollo, left, with two friends on the houseboat they live on in the centre of Amsterdam, along Keizersgracht.

-

An artist’s floating home-studio along the Buiksloterkanaal, north of the city.

-

Leentje Schade, 45, a dentist, with one of her chickens. She raises them in the henhouse on the roof of her houseboat in the city centre along the Keizersgracht. Hagen Harvey, 26, relaxes with a book at his home along the Keizersgracht.

One element flows through this country’s history, shaping its physical geography, permeating its inhabitants’ lives and forging their character: over millennia, the Netherlands, and the Dutch, have been fashioned by their relationship with water.

-

Pride 2025 celebrations along a canal in Amsterdam.

Nearly a third of the country lies below sea level. Almost 20% is reclaimed (a process that began in the 14th century). Half could flood; a fifth is water. Canals, rivers, lakes, sluices, windmills, polders, dikes, dams, storm barriers: these are the Netherlands.

No Dutch person is ignorant of the threat of water. In January 1953, a combination of severe gales and a spring tide meant the North Sea breached the dikes and more than 1,800 people died in the worst flood in the Netherlands’ history, the Watersnoodramp.

-

Visitors watch a video at the Watersnoodmuseum (Flood Museum) in Ouwerkerk in the south-west of the country, about the January 1953 flood when the North Sea broke through the dikes in several places.

-

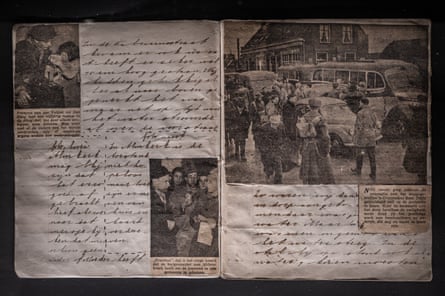

The diary of Piet de Peuter, a 12-year-old boy from Almkerk, who kept a journal of events and newspaper clippings during the January 1953 flood.

-

Visitors at Amsterdam’s Houseboat Museum along Prinsengracht, which tells the story of life onboard a houseboat. The museum is in a former cargo ship where the captain lived with his family. It was subsequently used as a floating house from 1967 to 1997.

That paved the way for the colossal Delta Works, the world’s largest flood protection system and a Dutch water management marvel to equal the monumental 32km Afsluitdijk that, in the 1930s, helped dam the Zuiderzee and turn it into the IJsselmeer.

Near-disaster struck as recently as 1995, when dikes along the rivers Waal, Maas and Rhine threatened to give way, leading to the country’s biggest evacuation since the second world war: 250,000 people, and nearly a million head of livestock.

That led in 2006 to the Dutch government’s “Room for the River” programme, which aims to allow certain areas to flood during periods of particularly heavy rain – a profound cultural shift towards adapting to, rather than resisting, rising water levels.

-

Agricultural fields along the River Zaan look almost like narrow islands floating on the water.

The climate crisis – and the prospect of inexorably rising sea levels, extreme rainfall and inevitable flooding – has fundamentally changed Dutch perceptions of their 2,000-year-old battle. The focus now is not on fighting the water, but living with it.

“There is a growing awareness that not all climate impacts can be prevented, nor all risks calculated,” said the researcher Carolien Kraan, a co-author of a significant report published this year on the concept known in Dutch as meebewegen.

Even in the Netherlands, Kraan added, there are limits to “the control that can be exerted over the environment. The question now is not whether we are going to use living with water strategies to adapt to climate change, but how and when.”

-

The spectacular Sluishuis residential complex in Amsterdam designed by the architect Bjarke Ingels to be carbon-neutral, surrounded by water and built on an artificial island in Lake IJmeer.

Henk Ovink, until 2023 the government’s water affairs envoy, put it this way: “Water is the enabler – if we understand its complexity, value it comprehensively and manage it inclusively. Then, water becomes the leverage for sustainable development.”

Enter the Netherlands’ expanding fleet of modern, sustainable floating houses. These are a far cry from traditional Dutch houseboats, typically former barges whose cargo space has been converted into accommodation or purpose-built “arks”.

-

Houses built on the water in the Zeeburgerbaai area of Lake IJmeer.

There are more than 10,000 such old-style houseboats around the country, almost a third of them in Amsterdam: once a desperate solution to the postwar housing crisis, many have since become as des-res as bricks and mortar (and almost as expensive).

Latest-generation meebewegen floating houses, however, are very different: architect-designed, usually part of entire new waterborne neighbourhoods, complete with solar panels, heat pumps, rooftop gardens and advanced sewage and recycling systems.

Some already exist, such as Schoonschip and IJburg on Amsterdam’s northern outskirts. Experts suggest such floating neighbourhoods could alleviate housing shortages – and even allow coastal communities to withstand the climate crisis.

-

The IJburg floating house district. Across more than 10,000 sq m there are 158 floating homes complete with bridges, roads and boat moorings, making it the largest floating district in Europe.

In the Netherlands, a dire housing shortage – the country lacks 400,000 homes, with an estimated 1m needed by the middle of the next decade – is expected to spur demand for floating homes, including in “Room for the River” areas likely to flood in future.

Farther afield, floating homes could even mean that as sea levels rise, the anticipated migration of hundreds of millions of people worldwide from coastal areas to higher ground could be slowed or partly avoided by allowing at least some to stay put.

Schoonschip, or Clean Ship, completed in 2020, consists of 30 sustainable floating homes equipped with 516 solar panels and 30 heat pumps. The IJburg floating house district holds 158 floating homes, making it Europe’s largest floating district.

-

The floating neighbourhood of Schoonschip in the Johan van Hasseltkanaal, located in Buiksloterham, in the north of Amsterdam.

-

Architects working at the Space&Matter firm, responsible for the urban planning of the floating neighbourhood of Schoonschip.

-

Philip van der Wees, a physical therapist and a professor of allied health sciences at Radboudumc, in Nimegen, looks out of his window at the canal in the floating neighbourhood of Schoonschip, where he lives with his family. A man on a boat paints the exterior of his floating house in Schoonschip.

Unlike houseboats, floating houses are generally fixed to steel columns plugged into sewer and grid systems. Prefabricated from timber, steel and glass, with concrete hulls, they ride up the columns when the waters rise, and descend when they recede.

Homes are not the only buildings that can float. Rotterdam – the Netherlands’ second-biggest city, more than 90% of it below sea level – now houses the world’s largest floating office block, an entire floating farm and a floating meeting and event space.

-

Sunset over the water from the artificial beach in Monster, where the Zandmotor project was carried out in 2011.

The meebewegen (literally meaning “move with”) strategy extends to the Netherlands’ coastal defences: the Zandmotor (sand motor) shifted about 21.5m cubic metres of sand to build a whole artificial peninsula near The Hague.

A driver for innovative coastal maintenance, the “motor” works with the water rather than against it: wind, sea currents and waves gradually spread the sand along the coast and into the dunes, strengthening the coastline for the future.

2 months ago

60

2 months ago

60