Paul Nurse is a turn up for the books. A Nobel prize-winning geneticist, former director of the Francis Crick Institute and erstwhile head of Rockefeller University in the US, his CV marks him out as one of this generation’s most eminent scientific figures.

But his presidency of the Royal Society, a position he has taken up for a second time, makes him rarer still. No other scientist in centuries has had a second term at the head of the academy.

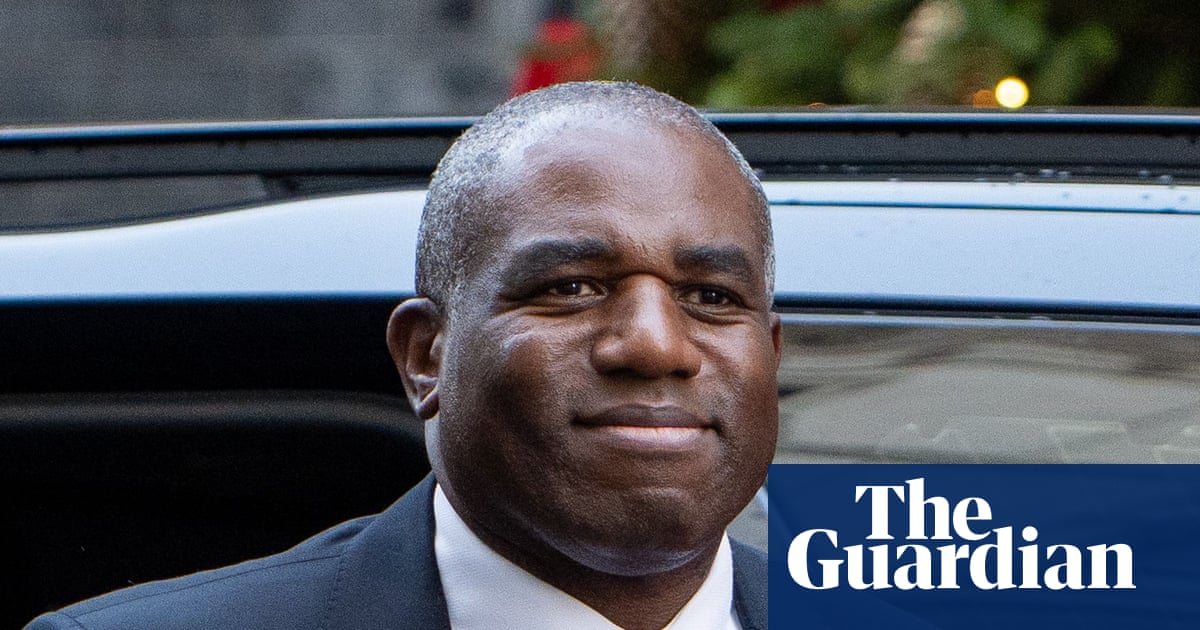

The unusual nature of the appointment is not lost on Nurse, nor is the controversy it has attracted. “I’m old, I’m white, I’m a man, so everything’s against me. And so I didn’t apply, but I was nominated anonymously by a number of people, apparently,” he says.

Sitting down with the Guardian at the national academy of sciences in central London, Nurse, 76, cuts an avuncular figure. But his appearance – a shock of white hair and a cosy knitted jumper – conceals a steely core: he has previously picked fights with influential figures who misuse scientific evidence and taken the British government to task for its handling of the Covid pandemic.

His reappointment as society president – he held the post from 2010 to 2015 – has been another battle. While some fellows supported his election, others argued it was time for a female president and that Nurse’s appointment gave the impression that the organisation, which was founded in 1660 and has always been headed by a man, was a “boys’ club”.

Nurse seems adamant he is the right person for the job, pointing out that, unlike in his previous presidency, there were multiple candidates and an interview. “The key thing for me was that you had to get two-thirds of the fellowship to vote for you,” he says. “So that persuaded me that it was sort of semi-democratic.”

He pushes back against the view of some fellows that it is a poor reflection on the society that it could not find someone else from among its 1,500 distinguished scientists. “It’s not an easy position to fill,” he says, noting that since the job is unpaid it is hard for most people to take, whereas he is retired.

“It is actually difficult. You’re always in the headlines, you’re always being challenged in different ways … And so lots of people don’t actually really want to do it, to be perfectly honest,” he says. “Some people think it’s an honorific position only … but this is actually a real job. Now, I have done a lot of things, I am not a bad scientist, and that really matters in this game because it opened all sorts of doors internationally and also in government.”

And then there are the other scientists. “The fellowship, which, as you said, [numbers] 1,500, they give you a hard time,” he says.

Whether or not such challenges would really be beyond another scientist, Nurse is in the process of moving back into the Grade I-listed building that houses the Royal Society.

Looking around his residential apartment, it is clear that the presidency has its perks: Nurse’s balcony, on which he has set up a small weather station, looks out over the London Eye and Big Ben, while enormous skylights illuminate the spacious hallway.

Yet Nurse, who has taken over from the mathematician Adrian Smith, has also inherited a headache: Elon Musk.

The tech billionaire was elected a fellow of the Royal Society for his work in the space and electric vehicle industries. Some scientists have argued he should face disciplinary action, saying incidents including calling the British MP Jess Phillips a “rape genocide apologist” and his role in the “department of government efficiency” (Doge), which made huge cuts to US research funding, violate the academy’s code of conduct. The society under Smith, however, decided Musk would not face an investigation.

Nurse says it is “an immensely complex situation” and points out that the society has expelled only two people in 370 years. He says one problem is that the code of conduct resembles those used by an employer, and it may need to be looked at again.

“We elect people for scientific achievement or delivery. And therefore my view is that we get rid of them if that turns out to be false or not correct,” he says. “The fact that [Musk] comes and talks in rightwing rallies is irrelevant. I abhor it, I hate it.” But as for the view it is a reason for ejection? “I don’t agree with that, in actual fact.”

Nurse says Musk’s attacks on science in the US through Doge did cause concern, and adds that he wrote to him as president-elect, eventually suggesting Musk consider whether he wanted to remain a fellow of the society given its role in promoting science. “He did not reply to that,” Nurse says.

He says the situation around Musk “was made worse by not trying to deal with it quicker” but maintains that his approach was forceful enough given his own view that fellows should only be expelled for fraudulent science.

“I mean, it does get complicated because, look, let’s take Patrick Vallance. Now, if he cuts the science budget as minister of science, do I attack him? My view is that we can criticise but I wouldn’t throw him out of the society for that.”

Whether the stance will convince detractors remains to be seen, not least as there are signs Musk is rekindling his relationship with Donald Trump. But Musk isn’t the only potential difficulty in the political landscape.

“I think rightwing populism is an issue because science depends on the pursuit of truth, evidence, rational thinking [and] courteous debate, actually, all of which is missing in the right populist way of thinking,” Nurse says. “And we see the same thing with Reform in this country.”

And there are other challenges Nurse wants to address, from how science in the UK is funded to the UK’s visa system, which he has said is deterring early-career researchers.

What does he make of the view raised by some that it is concerning that one scientist should have so much influence over UK science, and for so long?

“It troubles me too because, I mean, we should be all self-critical and so on,” he says. “But I’m actually more modest than that. I’m not a power nut.”

8 hours ago

7

8 hours ago

7