If painting is a fast car, drawing is more like taking the bus. At least that’s how it felt to me, puttering along on the 27 to Paddington that is the National Portrait Gallery’s trawl through Lucian Freud’s sketches, engravings and even childhood crayonings, daydreaming until my stop, with the occasional flash of colour and flare when one of the exhibition’s “carefully selected group of important paintings” rolled past.

This is a sad review to write. Freud seemed an unquestionable genius in his lifetime and I still stand in awe of the great modern paintings with which he won that crown. One of his 1990s portraits of “Benefits Supervisor” Sue Tilley towers here, in every sense, her face slumped into her hand as she sleeps vertical in an armchair, while Freud eagerly inspects every pore and blemish on her big naked body and translates her into an ecstasy of oily greys, whites, purples, ridged, pockmarked, magnificent.

But such peak moments are surrounded with so much dross it makes you doubt he was anything special. I wish I could lambast the curators for failing to do him justice, but when an artist leaves this many mediocre works for them to make a meal of, you have to face facts. Freud did churn out a lot of nonsense as well as his nuggets of greatness.

I’ve always tried to avoid looking at his etchings but they are shoved in your face here as if they were highlights of his late years. They teeter between ordinary and awful. There just isn’t the niftiness and daring of the paintings: faces and bodies are defined with matted, heavily shaded edges that seem precious as well as laborious. At best they are posters. Two prints of Tilley seem like adverts for his art rather than manifestations of it.

I laughed – and not kindly – at Man Posing, a 1985 etching of a nude model on a couch with his cock and balls up front between splayed legs. It’s not the genitals that are disappointing but his sad, stupid face, too big for the body. The result is weird without being witty or moving. Yet a small painting beside it of the same man in the same pose is dazzling, magic. The balls are deep pinkish red, flaming from his white flesh like a cockerel’s comb.

Freud is an albatross of an artist, glorious when he flies on canvas, clumsy when he stumbles about in earthbound black and white. It is hard to see why he even bothered with etching when he was hitting his peak as a painter – was it for an extra few bob, or the old-masterly connotations of this medium in which Rembrandt and Picasso excelled, or just the need for a graphic outlet? For the NPG does make its point that Freud started out as a draughtsman first – a precise, patient observer of thistles, dead monkeys and the human face – and a painter very much second.

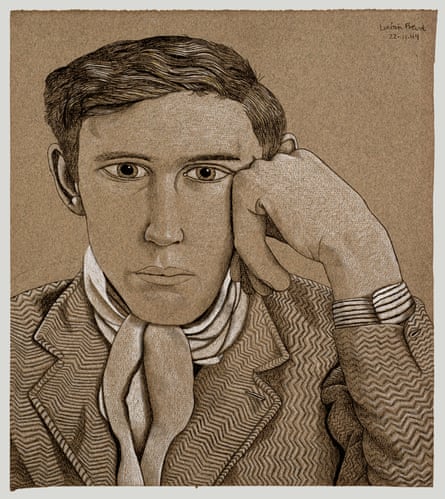

Yet his meticulous drawing style palls unexpectedly as one early work after another is stacked up – and as for his childhood pictures from Berlin, a kid could have done them. This is where the show starts to seem indulgent, confused, soppy. You thought Freud was tough and cruel? His drawings of Kitty Garman and other beauties, as well as himself and male friends from the 1940s and 50s, look sentimental. He loves a pretty face, and in his 1946 chalk and crayon drawing A Girl, desire softens his eye.

This Freud is a nicer man but a lesser artist. Perhaps what has gone wrong here is that curators and art historians who don’t remember Freud as a living artist, and don’t feel him as contemporary, are starting to reevaluate him as a historical figure who is “interesting” rather than urgent. They dismally succeed in redefining him as a minor British artist, doing careful, stylish drawings that he translated, in the 1950s, into modest paintings. But this Freud died. There’s a rift in the middle of the show when it announces that, in the 1960s, he abandoned his fascination with drawing to plunge into pure paint. His terrifyingly brilliant 1963 Self-Portrait, a painted hand grenade of squinting eyes and bruised-looking flesh, announces the years without drawing.

It’s at the moment he put down his sketchbook he became an artist who holds us. He chose paint – and painting from life, with models in front of him as he added another stroke of purple or black to their oily double. It may be that he was less intellectual than his mysterious personality suggested. He worked from instinct, not thought, and when he hit the vein he was great, but sometimes he missed. The NPG concentrates on the misses.

Why put on such a perversely stupid exhibition? I’ve heard it said that Freud’s great paintings are hard to borrow because so many are in private hands. But if Freud’s collectors really are so uncooperative, they are risking their own investments. A few more shows like this and his prices will fall off a cliff.

-

Lucian Freud: Drawing Into Painting is at the National Portrait Gallery, London, 12 February to 4 May

2 hours ago

4

2 hours ago

4