Paper tablecloths, blazing sun, spitting grill, plastic chairs, dishes of tzatziki, an expectant cat sidling up to diners: we could be in Greece. “It’s like a holiday,” marvels guitarist Joff Oddie, sipping an enormous iced coffee. But Wolf Alice are not on a Mediterranean jaunt – they’re at a restaurant on an industrial estate in Seven Sisters, north London, a few doors down from the studios where they wrote their upcoming fourth album The Clearing and its chart-topping predecessor, Blue Weekend. “We used to call this street Anchovy Mile,” reminisces front woman Ellie Rowsell. “Because it smelled like fish.” That might be the tip round the corner or, thinks bassist Theo Ellis, a nearby brewery (“something to do with filtering through fish scales”). Either way, such an odour would only cement the seafront ambience of “Costa del Tottenham”, as Ellis names it.

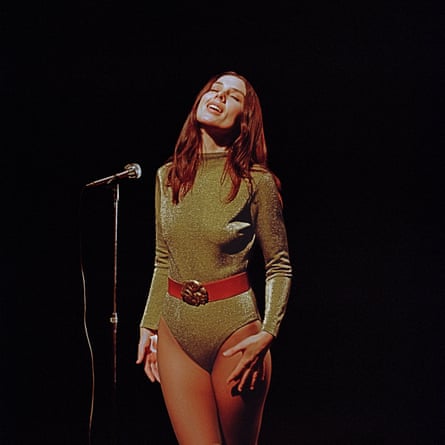

The only thing that could disrupt the serenity of this scorching Wednesday lunchtime is a spin of Wolf Alice’s new single. Bloom Baby Bloom is a genre-bending rock bonanza: squealing guitars, bone-shaking bass, ostentatious drum fills, but also honky tonk piano and a dreamy pop chorus. Throughout Rowsell veers between breathy folk croon and a hair metal wail. To underline the retro vibe – and the vocal gymnastics – the video has Rowsell writhing in a sparkly, glam cut-out leotard amid a Fame-style dance troupe; in the promo images she is clad in cherry-red hot pants and matching knee-high boots.

The band aren’t just going hell for leather aesthetically. After 2021’s Blue Weekend, the foursome left indie label Dirty Hit and signed with Columbia Records, part of Sony. The move to a major means more money for spangly Lycra – but is it also a sign of prospective world domination?

“English bands are so hesitant to ever admit ambition, but I am ambitious with this record,” says drummer Joel Amey. Sony has the ability to spread the word globally, says Oddie: “I’d like every person to be able to have the opportunity to say whether they like or don’t like Wolf Alice.” Ellis looks bemused: “That’s a dangerous thing to wish!”

By many measures, Wolf Alice are already colossally successful. They are Brit and Mercury award-winners, and Grammy-nominated. Blue Weekend reached No 1, while their first two albums only narrowly missed the top spot. In 2016, they were the subject of a Michael Winterbottom film; the director called them “the best band in the world”. They’re high up on next month’s Glastonbury bill. “In many ways, bucket lists have been filled like five years ago,” admits Amey.

They have transcended the folk-punk shoegaze of their formative years to become omnivorous guitar music masters, incorporating hardcore, chamber pop, country, industrial, funk and psychedelia. On The Clearing they nod to krautrock, glam and trip-hop; one song sounds like a bossa nova Carpenters, another recalls Steely Dan’s Reelin’ in the Years. Yet what made the band an instant success story remains the same – Rowsell’s precise, poetic millennial vignettes, and an ability to make every song stylish and memorable. As a genre, rock is experiencing a decades-long decline; there are no journeymen any more. “Our peers have come and gone,” says Amey. “We’re still here.” The only way to be a rich and famous – or even solvent and vaguely recognisable – rock band in this day and age is to be exceptionally good at it.

And yet, you might also consider Wolf Alice underrated. They’ve never had a hit single. Gratifyingly, their most popular song on Spotify is also their best – 131m streams for 2017’s Don’t Delete the Kisses, which preserves the turbulent ecstasy of fledgling love in hypnotic indie electronica – but that’s mostly due to a “really big” TV sync. Which was …? They puzzle over the answer. Heartbreaker? suggests Rowsell. Heartstopper! says Ellis, suddenly remembering the name of Netflix’s queer teen drama phenomenon. While Oddie seems the most business-minded (he tells me the band “wouldn’t work if it wasn’t making money”), Ellis and Rowsell clearly can’t fake an Ed Sheeran-style stats fixation.

It’s a decade since Wolf Alice’s debut album My Love Is Cool. Oddie’s face lights up when reminiscing about the low-stakes euphoria of nascent rock stardom. “Everything was a win. People coming up to you and saying that they liked your music; being buzzed about 20 people turning up to a gig in Leicester!” At that point they had been a proper band for less than three years – originally Wolf Alice was an acoustic duo comprising Oddie and Rowsell, who met via an internet forum. But nostalgia makes Rowsell shudder: she can’t believe her youthful chutzpah, performing songs she didn’t know on instruments she couldn’t play. “I didn’t even know …”

“Where A was?” says Ellis.

“I still don’t know where A is …” she mutters mordantly.

I first met the band in the run-up to that album’s release, and they remain meticulously self-deprecating. Ellis and Rowsell both grew up in north London and still live here, as does Oddie (Amey has moved to Hastings). On The Clearing’s sweetly harmonic closer, The Sofa, Rowsell reflects on youthful fantasies of escape to California, but sounds almost relieved at the prospect of being “stuck in Seven Sisters” for ever.

But Wolf Alice are not immune to the march of time. They are all now in their 30s, and The Clearing is a meditation on the first stage of the ageing process, a time when the “frantic” struggle to navigate adult life begins to ease, says Rowsell.

On Play It Out, a kind of self-soothing lullaby, Rowsell contemplates the rest of her life: a future without children and, eventually, parents. She wonders whether she’ll still be valued and adored “when my body can no longer make a mother out of me” – an anxiety partly prompted by acquaintances on social media posting about “their mums or their partners being mums. It was the nicest things I’d ever heard coming from men about women. I was like: oh my God, I hope that you can not be a mother and people can think you’re that amazing.” The proverb “the hand that rocks the cradle rules the world” was also stuck in her head: on Play It Out, Rowsell attempts to make peace with the inescapable spectre of motherhood, even if it only exists in the form of “an empty pram in my mind”.

Rowsell has an extraordinary ability to whittle her internal monologue into lyrics, but on The Clearing she begins to doubt her instincts. Opening song Thorns reflects wryly on Blue Weekend’s account of a devastating breakup – that she must be a “narcissist” to literally make a “song and dance” about the split. At the time, she claimed Blue Weekend was her least autobiographical album. “Yeah, I was lying!” she laughs.

In reality, the album combined real details with fictionalised elements, which often felt like the worst of both worlds. “I was like, maybe it’s not truthful, or it makes it sound worse.” Did she regret writing it? “I wasn’t sitting there being like: nooo,” she says, miming anxious despair. “Well, actually I was …” Rowsell still doesn’t know how much of her real life to put into her music. “What is the stuff that’s supposed to be kept for your DMC [deep meaningful conversation] with your mate? If I’m such a private person then why am I doing this?!” Does she find writing about her problems cathartic? “I must do because look how much stress it’s caused me!”

On the new album, Amey – too unwell to come to lunch, so we speak the following day – offers Rowsell a brief respite by taking the mic and pouring his own heart out. The sonic touchstones for the song White Horses were The Sunshine Underground by the Chemical Brothers, and Can; the lyrical inspiration was the lifelong mystery surrounding his heritage.

Previously, the 34-year-old had no handle on it. Taxi drivers routinely asked “if I was from where they’re from because of my dark colouring”, but he couldn’t say either way, because his mum and aunt were adopted. Then Amey’s family found out his grandmother was from Saint Helena – a discovery that chimed with the “strange in-perspective bullshit that starts happening in your 30s”. The resulting track alludes to his grandmother’s “very tough” journey to England and doubles as a love letter to his chosen family: his friends and bandmates.

Everyone agrees that they’re in Wolf Alice for the long haul. But while getting old in a band is par for the course for men, there’s an added self-consciousness for women. Rowsell ends Play It Out with an optimistic manifesto: she wants to “age with excitement – go grey and feel delighted”. She is “less worried” about her future as a frontwoman than she used to be, she says, partly thanks to a selection of inspirational peers, including Charli xcx, Caroline Polachek and Self Esteem.

All three of those women are knowingly camp and committed to mining cool from unlikely places – all of which Wolf Alice are doing in their flamboyant new era. When Rowsell, 32, was growing up in the 00s, zeitgeisty rock was “quite cold and aggressive, black and white, not warm” – think angular post-punk revivalists such as Interpol. The Clearing skews instead towards “softer and more colourful” 1970s guitar music; Fleetwood Mac, Pentangle and Steely Dan were all references. Liking soft rock was “embarrassing for so long”, she continues. “I don’t care any more.” The bold new look is an extension of this. When Rowsell was younger she agonised over wearing the right thing. “Now I’m so tired of caring that I just want to do something fun.” Not funny, though. “I don’t want people to think it’s a joke,” she says. “It’s self-aware, but not self-deprecating.”

The Clearing was recorded in LA, with Adele’s producer Greg Kurstin, but its gestation period ran from spring 2023 to the end of 2024. Rowsell says that witnessing everyone “noodling” and “pottering” in Get Back, Peter Jackson’s epic Beatles documentary trilogy, inspired a leisurely, tech-free, in-person writing process. Yet the band assure me it is merely a coincidence that the beginning of the album sounds so Beatlesque: Thorns’ pared-back piano intro and swelling strings land somewhere between Let It Be and I Am the Walrus. “Every song sounds a bit like the Beatles,” says Oddie. “They invented everything.”

They are well aware that having such space and time is a luxury for a band, especially in the current economic climate. Costs of touring have almost doubled since they started, Oddie explains, but ticket prices have only increased by a small amount. Plus, it was hard enough back then – the foursome were only able to make tours viable by cramming themselves into a single small hotel room or sleeping on friends’ floors. The tacit agreement was that the stay would turn into a party, say Oddie. “You’d be having big nights out for weeks on end, it was exhausting.” But even that didn’t last. “If your friends start leaving uni and you’re doing a regional tour, you’re like: I don’t actually know that many people in Sheffield now I’m 23,” says Ellis.

Last week, Oddie told MPs in a parliamentary meeting that he didn’t know how his band would survive if they were starting out today. He was giving evidence as part of an effort to safeguard the future of live music in the UK amid rocketing costs and shuttering venues, suggesting a £1 levy on tickets for larger gigs, with the proceeds going to support up-and-coming acts on tour (the band are donating £1 from each UK ticket sale to help grassroots venues).

His appearance recalls the late 2010s, when Wolf Alice were never far from the cut and thrust of Whitehall. The band heavily endorsed Jeremy Corbyn in the 2017 election, played anti-Tory marches and kicked off their 2018 Brixton Academy show with Danny Dyer’s expletive-riddled viral rant about Brexit, in which he called David Cameron a “twat”.

Back then, they were driven by a genuine optimism about Corbyn’s message and the excitement of being part of a genre-uniting “youthquake”; 2017 was the year Stormzy paid tribute to the Grenfell victims and participated in pro-Corbyn chants at Glastonbury. It all seems like a very long time ago. Can they see themselves speaking out about politics again? “It depends if we’re represented by someone,” says Ellis. “Personally, I don’t feel particularly represented right now by many things.” Oddie thinks they should use their platform “sparingly – if you talk all the time about something, people switch off.”

The band’s focus is now on some secret-ish Irish dates (they never officially announced them; they sold out anyway) to warm up for that Glastonbury performance and Radio 1’s Big Weekend, although Ellis is concerned he might have forgotten “how to stand”. For their end-of-year arena tour, they’re hoping to transform their usually straightforward live show into a spectacle: the current West End production of Cabaret, which Rowsell recently took Ellis to see, may be an influence; there might be a wind machine. With an exceptional – if characteristically unconventional – new album and major label money behind them, perhaps Wolf Alice will also take things to the next level commercially this time. But global superstardom isn’t the be-all and end-all; to be honest, they seem more than happy on Anchovy Mile.

3 months ago

276

3 months ago

276