The death of Jack Bond in December last year brought an end to one of the most remarkable, and remarkably undervalued, chapters in British cinema. Bond is perhaps best known for the Pet Shop Boys movie It Couldn’t Happen Here, released in 1988; but that was just one pitstop in an unusually shaped career that took the form of, if not two halves, two distinct sections that in retrospect appear subtly intertwined.

Bond’s commission from the Pet Shop Boys stemmed from earlier work on The South Bank Show, particularly an episode about Roald Dahl in which the author encounters characters from his books – and in fact much of Bond’s career was occupied by what are essentially arts documentaries, albeit highly unconventional ones. He started off at the BBC in the early 1960s, with programmes about the first world war poets and George Orwell, culminating in a still-impressive film in 1965 about Salvador Dalí, called Dalí in New York, which investigated the constructed nature of Dalí’s artist personality by using, among others, “meta” shots of Bond himself discussing the filming process.

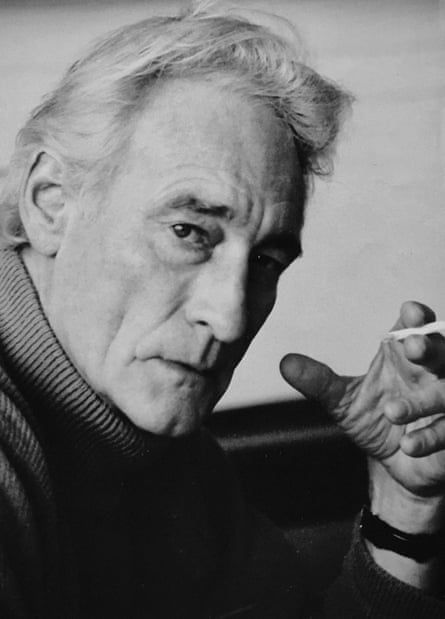

Dalí in New York was also significant because it was the first time Bond directed a well-known writer, actor and media intellectual named Jane Arden. It wasn’t the first time they had met, or worked together, but no doubt it cemented their creative relationship. Shortly afterwards, the pair would work together on what would become Bond’s feature directing debut in 1967. Separation, written by and starring Arden, is a cut-up, fractured account of a woman unhappily caught between a failing marriage and a younger lover she is uncertain about, all against the backdrop of mid-60s swinging London. The fact that Arden was herself in a failing marriage (to TV director Philip Saville) and in a relationship with a younger lover (Bond himself) is no doubt relevant.

Arden is a fascinating figure in her own right; apart from anything else, she appears to be the only woman in the whole of the 1970s to have a solo directing credit on a British feature film. That would be the next film she and Bond made together, The Other Side of the Underneath, based on Arden’s happening called A New Communion for Freaks, Prophets and Witches, which she developed with her all-female theatre company Holocaust. Having been a successful playwright and TV writer, it is clear that in the period since Separation, Arden had absorbed the most radical ideas of the time, from anti-psychiatry to encounter-group therapy. The Other Side of the Underneath, which Bond produced and appeared in, is one of the most extraordinary, if deeply unsettling, films to have been made in the UK.

Perhaps the stress of making it suggested to Arden she should share the directing of their third film, Anti-Clock, with Bond It is a bizarre, hermetic, and often baffling fable featuring one of Arden’s sons, Sebastian Saville, who plays both a therapy subject and the professor attempting to treat him. Arden’s motives, though, remain obscure; she killed herself in 1982 and Bond subsequently withdrew from circulation the films they made together. Twenty-five years later, however, they were rediscovered and reissued by the British Film Institute, an amazingly valuable act of cultural archaeology.

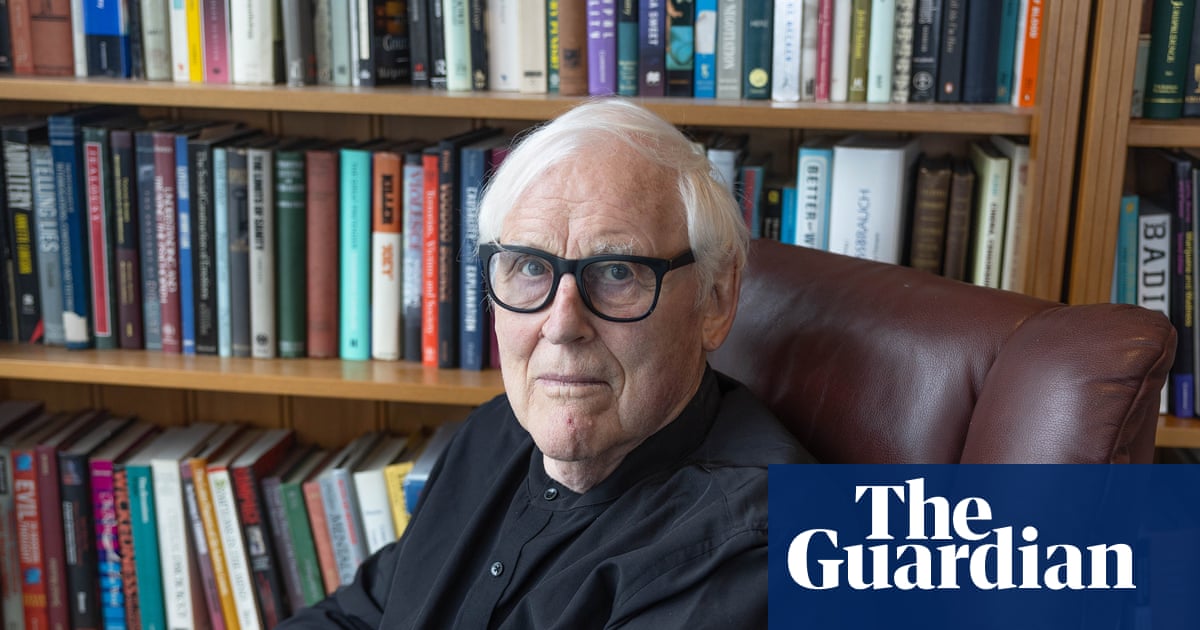

Arden’s death closed a chapter. In retrospect, Bond’s part in it looks like an extension of the improvisatory, boundary-breaking style he brought to his documentaries – which, if you squint a bit, could also include It Couldn’t Happen Here. Bond continued to make films focusing on creative personalities – notably The Blue Black Hussar in 2013 which allowed Adam Ant to ruminate on the mental health crises that derailed him some years earlier. Perhaps if Bond had made a successful awards-bait feature, or if Arden had been more inclined to create a conventional narrative, either or both of them might be more widely known, or sustain a more significant place in British film culture. Be that as it may, their films, along with Bond’s solo work, are fascinating in their own right, and unquestionably worth seeking out.

3 months ago

96

3 months ago

96