Wooden stakes bearing pictures of young men were driven into the yellow sands of Copacabana beach this week, opposite Rio de Janeiro’s swanky hotels on Avenida Atlântica where 300 mayors and their entourages were staying during the C40 World Mayors Summit.

Smiling up at the mayors in their hotel suites were photographs of four officers killed in what was the deadliest police raid in Brazilian history, just a few days before the summit. A further 117 people were killed in the operation in two of Rio’s largest clusters of favelas – the Complexo do Alemão and the Complexo da Penha – in what the police said was a clampdown on organised crime.

The raid attracted timely headlines and even approval for the regional governor, Cláudio Castro, an ally of the former president, Jair Bolsonaro, a climate change denier.

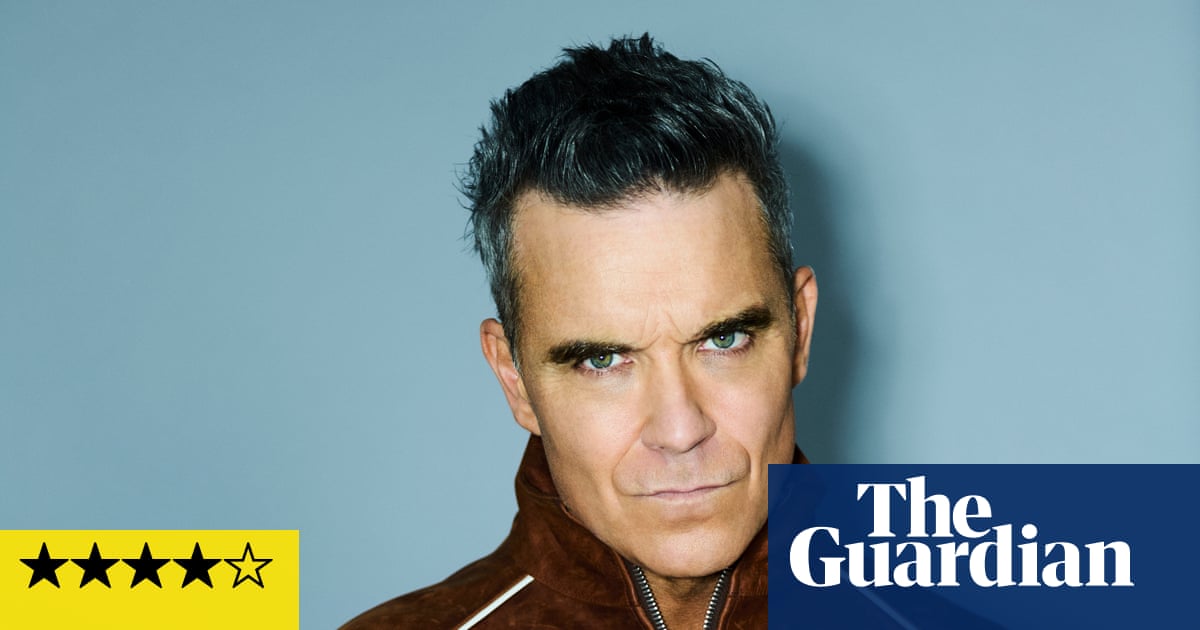

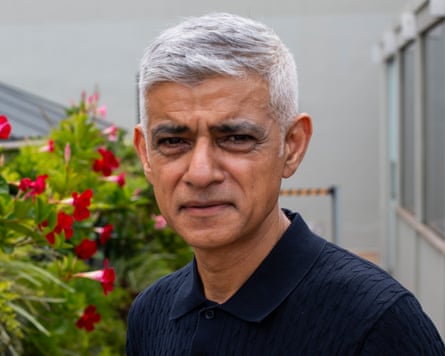

The protest was an inauspicious start to a week in which Rio was hosting not only the C40 World Mayors Summit on climate change, co-chaired by London’s Sadiq Khan and Rio’s Social Democratic mayor, Eduardo Paes, but also Prince William’s Earthshot prize event. On Monday, Cop30 climate talks will start in the port city of Belém, 2,000 miles to the north.

Last week, the UN secretary general, António Guterres, acknowledged in an interview with the Guardian that it was now “inevitable” that humanity would overshoot the target set in Paris in 2015 of limiting global heating to 1.5C (2.7F), with “devastating consequences” for the world.

Globally, despite extreme heat, floods and devastating wildfires, populist leaders, some sceptical but others in outright denial about the science, are talking up the costs of action rather than the consequences of inaction.

The purpose of the mayors’ summit, Khan says, is to push regional politicians, often backed by more progressive urban electorates, to go further in doing something about it.

Cities account for 75% of global carbon emissions, he says. It was repeatedly noted that the second-biggest delegation after the Brazilians at the summit was the US one, with about 100 mayors attending in defiance of the White House – no high-level members of the Trump administration are expected to attend the Cop30 talks.

Khan says: “Mayors across the globe, and I include London, are good examples of leaders, politicians, actually taking action.” His fellow city leaders are not just tinkering at the edges, he says, but seeking to turn the tide in the face of deniers such as Donald Trump, swirling misinformation, a doubting public and thorny, even violent, local politics.

We talk to six mayors on what they are doing about the climate crisis:

Yvonne Aki-Sawyerr

Mayor of Freetown, Sierra Leone; population 1.4 million

It had been a difficult few days for Yvonne Aki-Sawyerr. Shortly before getting on a plane from Sierre Leone in west Africa to Brazil a lorry drove into her parked car on a street in Freetown, crushing the side in which she usually sits.

She was not in the car at the time but then half an hour later it emerged that her driver’s house was on fire. What caused that? “Unknown, unknown,” she says.

“But there are a few things going on: I’m running for president, and I’ve been very vocal on narcotics,” she adds, calling it: “A series of unfortunate events.”

It is not the first time she has had to face such threats but, she says: “You can’t obsess about it or you wouldn’t get anything done.”

The impact of extreme weather, landslides and flooding has led to a burgeoning population in Aki-Sawyerr’s city, as subsistence farmers have concluded that they cannot make a living off the land.

In 2015, the city’s population was just over a million. That is expected to double by 2028. One consequence is a rising number of informal settlements replacing forests on the hillsides around the capital, and ever more logging to feed the wood-burning stoves that remain widespread, adding to the city’s carbon emissions.

Aki-Sawyerr has few powers as mayor beyond sanitation. Much of her time is spent trying to use her role to get international financing for projects such as a cable car system to reduce vehicle emissions, or the planting of 5 million trees by 2030.

But how to stop people cutting those trees down? That’s where her sanitation powers come in. “We’re actually converting faecal sludge into briquettes as an alternative cooking fuel,” she says.

“It is odourless, it’s dried, it’s carbonised – and by the end of December, we will have a machine that we’re importing that will enable us to produce the briquettes at scale.

“We’ve tested in homes, we’ve put them out to communities, and they’ve been really well received. What we haven’t been able to do is to produce them at scale.”

Giuseppe Sala

Mayor of Milan, Italy; population 1.4 million

It amazes Giuseppe Sala, a member of the Italian Green party and the mayor of Milan for nearly 10 years, how little he sees of Giorgia Meloni, the far-right prime minister of Italy. She has been to the city perhaps three times in as many years, he says.

She has, however, expressed her concerns about the “ideological” nature of the European Green Deal plan to become the first climate-neutral continent by 2050.

One of the projects Sala thinks the rest of Italy could learn from is a campaign called “I don’t waste”, which involves primary school pupils being given a reusable bag to take home any uneaten food from school lunches. City hall calculations suggest it saves approximately 10,000 sandwiches, 9,000 pieces of fruit and 1,000 desserts from being wasted every month.

He has also brought in a low-emission zone to Milan, the largest in the EU that bans non-compliant cars. Milan remains congested but the air quality is improving and after a difficult first year it has been accepted by the public, he says.

Two months ago, he banned private vehicles entirely from the roads around Via Monte Napoleone, the city’s fashion centre. “Always make step by step,” he says, though he expects the 2027 mayoral election to be dominated by the issue, with his opponents insisting: “You have the right to drive your car where you want.”

“So that will be a good moment to see if the sensitivity of the people could change,” he says.

Nick Reece

Mayor of Melbourne, Australia; metro population 5.4 million

It was when a new planning application for a £100m datacentre came across his desk that Nick Reece, lord mayor for a year in the south-eastern Australian city of Melbourne, started asking questions.

“I was asking the team: what’s the energy consumption going to be of this new data centre?” he says. The answer was that these computing facilities would account for a fifth of the city’s energy consumption by 2040.

He is now lobbying for a national and international set of rules to govern datacentres. “If we don’t get some framework in place, which means that these new datacentres are principally powered by renewable power, then we are not going to be able to achieve our carbon-reduction targets,” he says.

“We don’t want to see a race to the bottom around artificial-intelligence infrastructure.”

Reece also wants companies to consider how to best use the energy produced by the centres, such as heating swimming pools in the city, which often rely on gas-fired boilers.

“In the race to become smart cities, we don’t want to cook the planet,” he says. “That would be ironic and a tragedy.”

Kate Gallego

Mayor of Phoenix, US; population 1.6 million

Last year, the city of Phoenix, Arizona, broke its own temperature record with 113 days above 100F (38C). “We hit 110 [fahrenheit] in October, which had never happened before,” she says.

“Close to Halloween, the pumpkins that my kids had, they sort of melted. It really was very serious. The first week of school for my eight-year-old [this year], we had 118[F]; they couldn’t go outside,” she says.

“I think that has helped us with the political consensus.”

Even for Phoenix, a city in the desert, this was extreme but looking across the world it was an extraordinary year. “We talked to the UK’s fire department about how we manage heat and how we keep our firefighters safe during heatwaves,” Gallego says.

While Phoenix burns, however, Donald Trump has turned off the financial taps. “We benefited enormously from the renewable energy tax credits, so losing those has been very difficult, and makes it more complex to finance projects,” she says.

“We received a significant grant called Solar For All [for low-income and disadvantaged households], which we are losing. Our electric vehicle spending grants have been suspended.

“The change in administration has dramatically impacted the amount of federal support we received.”

The state of Arizona voted for Trump, but Gallego says the extreme temperatures meant there was significant support for policies that both reduced emissions, such as investment in a light railway, and offered some mitigation, such as coating pavements with cooling materials so they absorb less heat, lowering the temperature of the streets and ensuring fewer potholes emerge as a result of the asphalt expanding and shrinking.

Carolina Basualdo

Mayor of Despeñaderos, Argentina; population, 9,000

It is yet to be seen whether anyone from the Argentinian government will turn up in Belém for the Cop30 climate talks. Like Trump, the country’s president, Javier Milei, does not accept the scientific consensus about the human-made impact on the climate. He has called the crisis a “socialist lie”.

What this means for Carolina Basualdo, the mayor of a small city in the Córdoba region in the centre of the country, is clear. “We get nada, nothing,” she says when asked about government funding for policies designed to mitigate the impact of climate change.

The impact of the crisis on her city is clear, she says. It endures three heatwaves a year these days; hot days can be followed by storms, with hailstones the size of tennis balls. Basualdo has rolled out a programme of solar panels on roofs, standardised the temperature at 24C (75F) in municipal buildings to save on energy consumption from air conditioning, and is using pruning waste from parks as an environmentally friendly source of firewood for boilers.

Plastic polytunnels used by farms for the production of fruit are recycled into bags and wallets by women at a local gender violence refuge. The mayor, with funds from Bloomberg Philanthropies, was able to help a local basketball club to replace its granite floor with one from two tonnes of plastic bottle caps collected by the community. “We’ve been working very hard,” she says.

Evandro Leitão

Mayor of Fortaleza, Brazil, population 2.7 million

“He was isolated and just did what he wanted,” says Evandro Leitão, mayor of Fortaleza, the fourth-biggest city in Brazil, known for its stifling heat. He is talking about Jair Bolsonaro, the former president who was jailed in September for 27 years for conspiring to overturn his 2022 election loss to his left-wing rival, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who is in the same Workers’ party as Leitão.

Bolsonaro slashed environmental protections and promoted clearing and settling the Amazon rainforest. His administration oversaw a 60% increase in deforestation rates – the highest relative increase in a presidential term since satellite monitoring began. Lula has signalled that he wants Brazil to be a climate powerhouse, investing in renewable energy and forest conservation.

In the last 10 months that he has been mayor, Leitão has overseen the latest construction of micro-parks in his city, expanding the amount of green space by 40%, equivalent to 4,100 football pitches in five years.

There are, however, concerns being raised about the Brazilian government’s recent announcement that it is suspending the soy moratorium, which recognised deforestation as a threat posed by clearing land for the legume.

Brazil’s state oil company Petrobras has also been given permission to drill for oil near the mouth of the Amazon River. “You have to be a great balance between the development of the country, but also to preserve the green areas of the country,” Leitão said. That’s a challenge that I have to struggle with, too.”

Travel costs to the World Mayors Summit were covered by C40, a group of 97 cities that have signed up to climate crisis goals.

Contact us about this story

Show

The best public interest journalism relies on first-hand accounts from people in the know.

If you have something to share on this subject, you can contact us confidentially using the following methods.

Secure Messaging in the Guardian app

The Guardian app has a tool to send tips about stories. Messages are end to end encrypted and concealed within the routine activity that every Guardian mobile app performs. This prevents an observer from knowing that you are communicating with us at all, let alone what is being said.

If you don't already have the Guardian app, download it (iOS/Android) and go to the menu. Select ‘Secure Messaging’.

SecureDrop, instant messengers, email, telephone and post

If you can safely use the Tor network without being observed or monitored, you can send messages and documents to the Guardian via our SecureDrop platform.

Finally, our guide at theguardian.com/tips lists several ways to contact us securely, and discusses the pros and cons of each.

Illustration: Guardian Design / Rich Cousins

2 months ago

70

2 months ago

70