It was the moment comedy broke with sexism – yet it happened in a strip club. It was a fervour of free creative expression – yet it retained a commercial, careerist edge. It was one of the longest-running and most successful brands in UK comedy history – which few people could now recognise.

At the Edinburgh fringe this summer, The Comic Strip Presents … will be memorialised in a series of film screenings and Q&As with its creator and prime mover Peter Richardson. Richardson was the impresario behind the legendary comedy club The Comic Strip, which opened in 1980. When he and his star performers – Rik Mayall, Alexei Sayle, French and Saunders among them – created Channel 4’s The Comic Strip Presents … a couple of years later, he could legitimately claim to be the man who brought alternative comedy to television.

This being a celebration of an iconic moment in UK comedy history, one might assume Edinburgh’s Usher Hall or the 750-seat Pleasance Grand has been set aside to host. But one might assume wrong. “When I started [showing these films] about a year ago,” Richardson tells me, “we didn’t have the money to advertise them. So we’d arrive at theatres that had about 30 people who had somehow read our minds that we were going to be there. And 30 people in a 300-seat cinema can be hard work.”

The Comic Strip Presents … ran for three series on Channel 4 from 1982-1988, then it moved to the BBC in the early 90s before making a return to Channel 4 for one-off specials, the most recent in 2016. But it’s not a big name in comedy – far less so than, for example, The Young Ones, the BBC sitcom starring some of the same talents and broadcast at the same time.

“It wasn’t good television,” admits Richardson, “because it wasn’t repetitive, and television is about repeating a formula and people getting to know it well.” And was it even comedy? One of the show’s stars, Mayall, argued that it shouldn’t have been called The Comic Strip, and that “Interesting Films” might have been a better fit. In fact, the series was – like Inside No 9 more recently – a tonally varying anthology show, a suite of standalone films united only by sensibility, and by the performers bringing them to the screen.

“I told Channel 4,” says Richardson, “‘These performers are so good they don’t need to be stuck playing one-dimensional characters. They can play all sorts. One week they can be a heavy metal band, the next week they can be The Famous Five.’ You could call it bad television, because you’re not seeing more of the same. But as it’s gone on, it’s become a collection of very memorable one-off moments and that’s what people now remember.”

The performers also included Adrian Edmondson, Nigel Planer and Richardson himself, with a rotating supporting cast that included Keith Allen, Robbie Coltrane and more. At the time, they were setting the UK comedy scene ablaze. That all started at the Comedy Store, a strip club and the anarchic HQ of what had recently been called “alternative comedy”. Richardson’s coup was to cherrypick the most exciting voices of that generation, and cart them off to another strip club, a little less anarchic, a few blocks up the road: the Raymond Revuebar. Here, with the financial support of the Rocky Horror Picture Show producer Michael White, he opened The Comic Strip club – a name that seems obvious, although “the New Depression Club” was, according to Edmondson, a very near miss.

For a year from 1980-1981, the Comic Strip was the hippest and hottest comedy night in town. “The bouncers at Raymond Revuebar had a simple rule of thumb for who was directed where,” Sayle later wrote. “If they reeked of aftershave they were sent to the strip show; if they smelled of beer they came to us.” Celebs piled in: Bianca Jagger, Dustin Hoffman. Robin Williams came and demanded to perform, to impress his guest, David Bowie. Sayle offered him 15 minutes. Williams said: “I told [Bowie] I’d do an hour”. Sayle: “You can’t.” Williams: “I’ll buy the club!” Sayle: “We don’t own it. It belongs to a bouffant-haired pornographer.” The buzz even reached the pages of the London Review of Books, whose critic noted, “within seconds, [Sayle] has the audience agape. Most of them, it seemed, had never been called cunts before.”

Then Channel 4 came calling, looking for cutting-edge talent to help launch the new broadcaster on to the country’s airwaves. Richardson was given carte blanche. “They said, ‘What do you want to do?’ and I said, ‘I want to make six films, all different.’” The first, Five Go Mad in Dorset, was transmitted on the station’s opening night, and the controversy around its satire of Enid Blyton attitudes gave that event a front-page news fillip. But Five Go Mad will not be celebrated at the fringe this summer, says Richardson. “Taking the piss out of racism and sexism [in that way] is long gone,” he says. “It’s not a funny issue like it was when we did it in the 80s.”

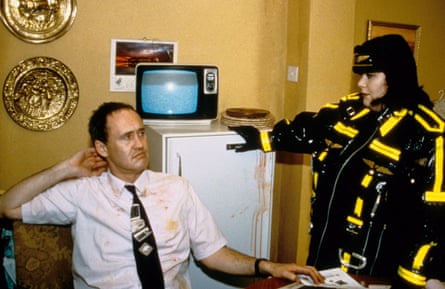

One option might have been to re-edit the episode – a course of action in which Richardson, now 73, has freely indulged as the Edinburgh shows have come together. Not for him a bask in the glory of his youthful success. “What we’ve done,” he says, “is revisited the films and said, ‘30 years later they need some adjustment.’ Because things go faster now.” Western spoof Fistful of Travellers Cheques has been “cut back a bit”. So too has late-period favourite Four Men in a Car. And a scene has been trimmed from The Strike, the show’s faux Hollywood movie making mincemeat of the miners’ strike. That one bagged a Golden Rose of Montreux comedy award, and starred Richardson (the only performer to appear in every episode) as Al Pacino playing, er, Arthur Scargill. “I could do Pacino much better now,” he laughs, “because I worked with John Sessions on Stella Street.” So now, he says, slipping into a convincing Italian-American accent, “I can do Al.”

Stella Street was another of Richardson’s TV hits, undertaken when The Comic Strip Presents, by any measure his life’s work, was in abeyance. Even when he was a jobbing comedian, in double act The Outer Limits with Nigel Planer, Richardson was a child of amateur film-makers and a wannabe film-maker himself. With The Comic Strip, he made movies for cinematic release: The Supergrass in 1985, and Eat the Rich two years later. Further TV specials included Red Nose of Courage, telling the tale of John Major’s flight from the circus to parliament, and 2011’s The Hunt for Tony Blair, imagining the ex-PM on the run having been accused of a series of murders.

Both will be screened at the fringe, MC’d by comedian Robin Ince and with special guests including Sayle and Allen. Richardson is modest about the achievement of having brought these 30 years’ worth of films to the screen. “I always thought we were the new Ealing comedies. And [Ealing Studios at its peak] made about 150 films over 20 years, of which about 15 are remembered. So our strike rate isn’t too bad. We made some flops, but at least one or two out of each series are really good.”

Some, indeed, are carved on this writer’s heart – notably Bad News Tour and More Bad News, the show’s two-part heavy metal spoof, which predated This Is Spinal Tap and ended up with Edmondson, Mayall and co performing live on stage, under a hail of beer glasses, at the 1986 Monsters of Rock festival at Castle Donington.

Richardson is at peace with the under-appreciation of The Comic Strip Presents, acknowledging that, as a bloody-minded sitcom refusenik way back when, he is the auteur of his own misfortune. He is delighted to be bringing the remastered films to Edinburgh, a city in which, back in the day, he and Planer once toured as a support act to Dexy’s Midnight Runners. “FrontmanKevin Rowland complained,” he says, “that we didn’t do new material at every performance.”

Expect no new material at these screenings – but a new experience, perhaps. “It’s a great thing,” says Richardson, “to show them in the cinema. You don’t often get to share comedy television with an audience, and it changes the whole experience: people laughing around you. We’ve discovered that there is an audience around the country who want to see these films on the big screen and talk about them. It’s fantastic that something we created 30 or 40 years ago is still creating laughter. I love it.”

3 months ago

91

3 months ago

91