There is periodic chatter over whether alcohol should be sold on concourses at Scottish football grounds. In public, clubs want to be seen to treat customers as adults. In private, they see the commercial benefit of flogging pints with pies. Punters noisily bemoan treatment as second-class citizens – you can have a beer while watching Scottish rugby – when in reality too many of them act in a manner befitting that status. When Ross County claimed a Livingston supporter spat in the face of their assistant manager at the conclusion to Thursday night’s playoff tie, the damning indictment was this became instantly believable. Scotland’s national sport has a serious behavioural issue, one which threatened to spiral long ago as authorities turned blind eyes. Adding alcohol to the mix would be absurd.

Jack MacKenzie has been deemed fit to play in Saturday’s Scottish Cup final as his Aberdeen team look to deny Celtic a domestic treble. Concern around MacKenzie had nothing to do with a hamstring or groin injury. Instead, the young defender was hit in the face by part of a seat after Dundee United fans invaded the Tannadice pitch last Sunday. United had reached the giddy heights of fourth in the Premiership. Pitch invasions have become normalised in Scotland at all levels, further evidenced by Partick Thistle’s contingent at Ayr United during another playoff game. Celebratory in essence, perhaps, but routinely with an aggressive undertone.

What happened to MacKenzie comes amid growing, misplaced entitlement in the stands. Celtic’s goalkeeper Viljami Sinisalo said “30 to 40” objects were hurled at him during this month’s Old Firm derby at Ibrox. A wine bottle was lying in his penalty area at one stage. Shards of glass were in the same penalty area for the same fixture three years ago. Arne Engels, the Celtic midfielder, was hit in the face by a coin at Ibrox in January. People are at risk of being assaulted at their workplace.

The response to such incidents is as feeble as it is predictable; condemnation from clubs and the Scottish football authorities, adjoined to the insistence that the police deal with culprits. Supporters are emboldened by a rising culture of aggression – fuelled by drink and drugs – and the knowledge clubs will suffer no serious repercussions. When Uefa properly tackled Rangers over sectarian singing two decades ago, it had impact. At home there was and is embarrassing inaction.

Case in point arrived in March. The Scottish Professional Football League announced Celtic and Rangers would each be docked 500 tickets for the next League Cup tie both play at Hampden Park. That’ll show them. This came four months after unacceptable conduct at semi-finals and three after similar antics at the final which were ignored. If Celtic draw Motherwell and Rangers play St Johnstone in next season’s last four, the drop of 500 in “name your allocation” will be irrelevant. What this case proved, eventually, is that the SPFL has rules relating to supporter conduct, rules it has continually ignored. The clubs call the shots in Scotland. The upshot is lame, unsatisfactory governance.

If Scotland’s football grounds were public houses, licences would be revoked. It remains curious the government or local authorities have not raised questions over safety certificates. Football clubs spend enough money on substandard players and the abomination that is VAR; they should be put under pressure to hugely increase policing and security contributions.

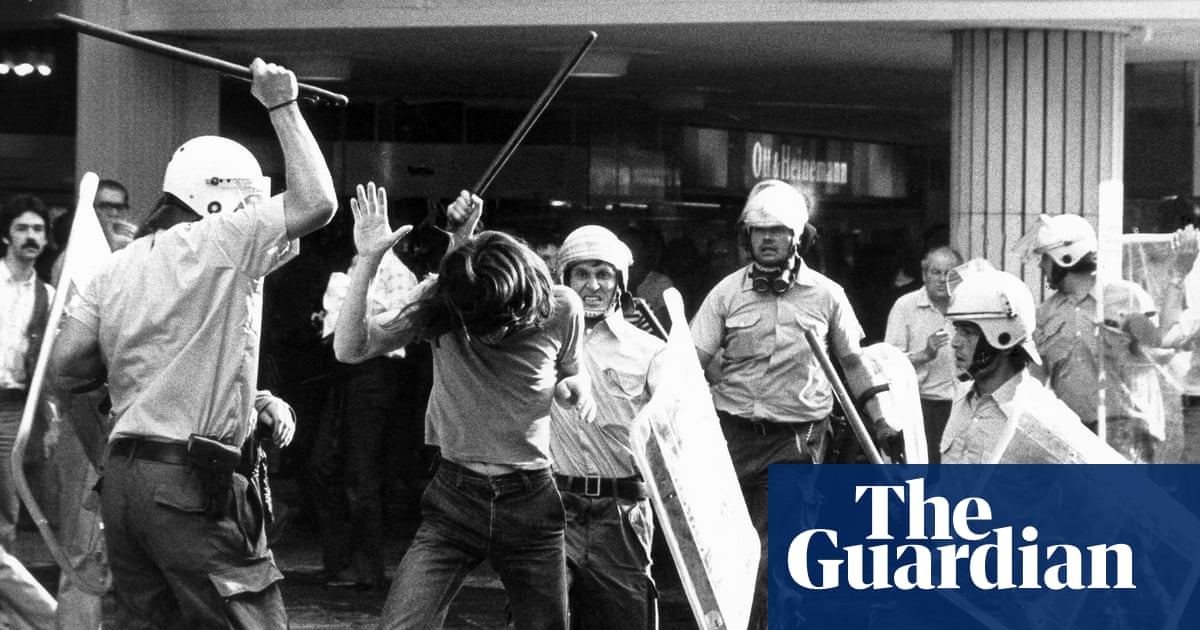

There is merit in the theory this is a wider, societal issue. Yet it is one attaching itself to football, which makes it football’s responsibility. There is no equivalent when Glasgow Warriors host Toulouse. Rory McIlroy is not hit by objects when the Open Championship visits Troon. From the 1970s, Scottish football had challenges with various groups – skinheads, mods, punks, rockers, teddy boys, casuals – and dealt with them. Now it has to try again. The status quo is unacceptable and unsafe.

after newsletter promotion

Ultras groups are not solely responsible for chaos in 2025 but they unquestionably fuel it. Celtic and Rangers give the impression they wish they had not created monsters with the respective indulgence of the Green Brigade and Union Bears, who have become a law unto themselves. Last weekend, a banner at Celtic Park essentially called for the removal of the chief executive, Michael Nicholson, whose crime is to have a social conscience and be protective of the reputation of his club. The Green Brigade’s previous tifos included the heralding of an IRA member who bombed a Belfast bar in 1975. They see nothing wrong with that in a football environment.

Fifty years on, there is not sufficient animosity to sense serious disorder between followers of Aberdeen and Celtic at Scottish football’s showpiece occasion. Still, the close season must be spent reassessing what the game wants its image to be. A noisy, angry minority are being assisted in dragging it into the gutter by the negligence of officialdom.

3 months ago

89

3 months ago

89