Inside the high-arched lobby of the Bank of England Museum, lines of women in flowing satin dresses twirl around men wearing stiff collars and black tailcoats. The room is filled with the sound of violins and conversation. The feathers and flowers on dancers’ heads sway as they laugh and chatter.

This Jane Austen-themed ball, in celebration of the author’s 250th anniversary, is one of many held by historical dance societies across the country. Enthusiasts of the Regency period, including fans of Netflix’s Bridgerton, come together to learn and perform the dances enjoyed by Austen and her contemporaries.

David Symington, 73, and Irina Porter (above left) became friends through such gatherings. “People who take part in these events get a lot of personal interaction – and that’s something we are gradually losing,” says Porter. “We often change partners, and introduce ourselves to other people. This lovely sense of community and personal interaction is very special.”

“It’s a really effective socialising space,” says Gemima Lodge, 40. “You see the same faces and start making connections.”

Costumes are an important element, with attenders commissioning specialist tailors, hand making their own dresses or sourcing Bridgerton-inspired outfits online. Mary Davidson, 26, and Lian Cooper, 37, sew together Regency-era dresses using old bedsheets, curtains and secondhand sarees. They became friends through their mutual love of historical dance and costume-making. “Everyone is so disconnected, stuck behind their phones now,” says Davidson. “We’re harking back to the old times. People have done this for hundreds of years and it’s really fun and social.”

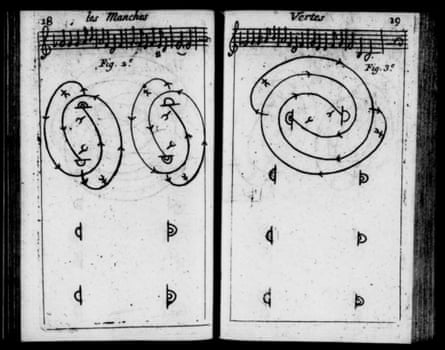

Putting on these events takes careful interpretation of 18th-century manuals, which instructed how to perform various social dances (or contredanses, due to partners standing opposite one another). Some, such as John Playford’s 1651 The Dancing Master, contain written instructions for the dances beneath sheet music. Others, such as Thomas Wilson’s, are filled with swirling diagrams known as dance notations, that represent a dancer’s movements across the floor.

The Beauchamp-Feuillet system, first published by Raoul-Auger Feuillet in his 1700 book Chorégraphie, recorded the steps of courtly dances in spiralling and geometric patterns. In his 1706 manual for contredanses, Feuillet omitted individual steps and laid out the patterns of how dancers will move across the floor – a system known as Simplified Feuillet. The book was translated into English by John Essex in 1710.

“It’s the first visual guide we get,” explains Jennifer Thorp, a dance historian and emeritus archivist for New College, Oxford. “You get the tune at the top of the page and then these floor plans telling people where to go. There were occasionally special symbols, because in some contredanses you might clap your hands or wag a finger at your partner. And people actually had the choice of what steps they were going to use.”

Dance notation is still used today, particularly in ballet. The Benesh Movement Notation uses five lines, like the stave on a sheet of music, to record the movements of the dancer’s head, shoulders, waist, knees and feet.

Paul Cooper, a member of the Hampshire Regency Dancers, transforms written instructions and diagrams into animations of Regency dances, making it easier for others to learn. “The instructions, as written, are close to being a computer programme,” says Cooper. “There’s iterative activity and a sort of algorithm to it. There are these little conditional statements: if one dancer does this, the other one does that. It’s all very mathematical in the way it’s expressed. Some of these dancing masters would probably do quite well in the modern world as computer programmers.”

Part of his work involves interpreting some of the ambiguities left behind by written instructions. “It’s often quite terse, and invariably leaves you with as many questions as answers. What does this mean? Is there something implied here that isn’t said? How do I go about interpreting that?”

Some dances also need to be adapted for modern tastes. The Triple Minor, a popular country dance in Austen’s time, involves three couples in a line that slowly alternate positions. The first couple performs most of the steps, while the third couple does little to nothing – a rare chance for young men and women to share a few words, out of earshot from their chaperones.

“But that’s not something we particularly care about in the modern world,” says Cooper. “We’re much more interested in enjoying the dance. So we’ve adapted that into a three couple set, where all of us get a turn at being the first couple, one after another. Everyone gets a pretty much equal amount of activity.”

Cooper met his partner and fellow Hampshire Regency Dancers member, Jorien van der Bor, at a historical dance event. “We were dancing, and I kept tripping on the carpet, and he kept steadying me,” she laughs. “I remember looking at him and going: ‘Oh, he is cute!’’

Van der Bor is an experienced caller – a term in country dancing for a person who teaches the dance to a group, and calls out the different moves as the music plays. “You’re orchestrating the room,” she says. “Sometimes, you give the instructions like a metronome all the way through. But I’ve also had groups where people know what they’re doing, and you call it once or twice, and then get quieter and quieter as everyone gets on with it.”

These societies offer history-lovers an opportunity to revive dances that may not have received enough appreciation at the time. The Duke of Kent’s Waltz, dated around 1802, is “quite a swishy” dance for the Hampshire Regency Dancers, according to Van der Bor. “It was probably not well-known at the time, but it’s become a favourite among the modern community.”

Another favourite is Mr Beveridge’s Maggot, the slow, stately dance performed by Mr Darcy and Elizabeth Bennet in the 1995 Pride and Prejudice TV adaptation. “From a strict, historian’s point of view, we probably shouldn’t be doing it,” she says. “It’s from well over a century earlier. But many people in our community just love that particular adaptation.”

Helen Davidge, the caller at the Bank of England Museum ball, puts her favourite as The Duchess of Devonshire’s Reel. It was choreographed by Charles Ignatius Sancho, who was sold into slavery as a child and later became a prominent composer and abolitionist. “It’s very intuitive,” Davidge says. “You’ll do a move and have your partner’s right hand, and the next bit also needs your partner’s right hand. So it’s already in place.”

Davidge founded the Georgettes of Oxford dancing society in 2023. Her interest in historical dance began as a way to build community, marry her love of history and ballet, and enjoy a bit of escapism. “The world is so busy, and sometimes quite a scary place,” she says. “To have a space to just come and focus on your body, dancing and sharing that with other people – it’s a little break from the busyness of life.”

2 hours ago

3

2 hours ago

3