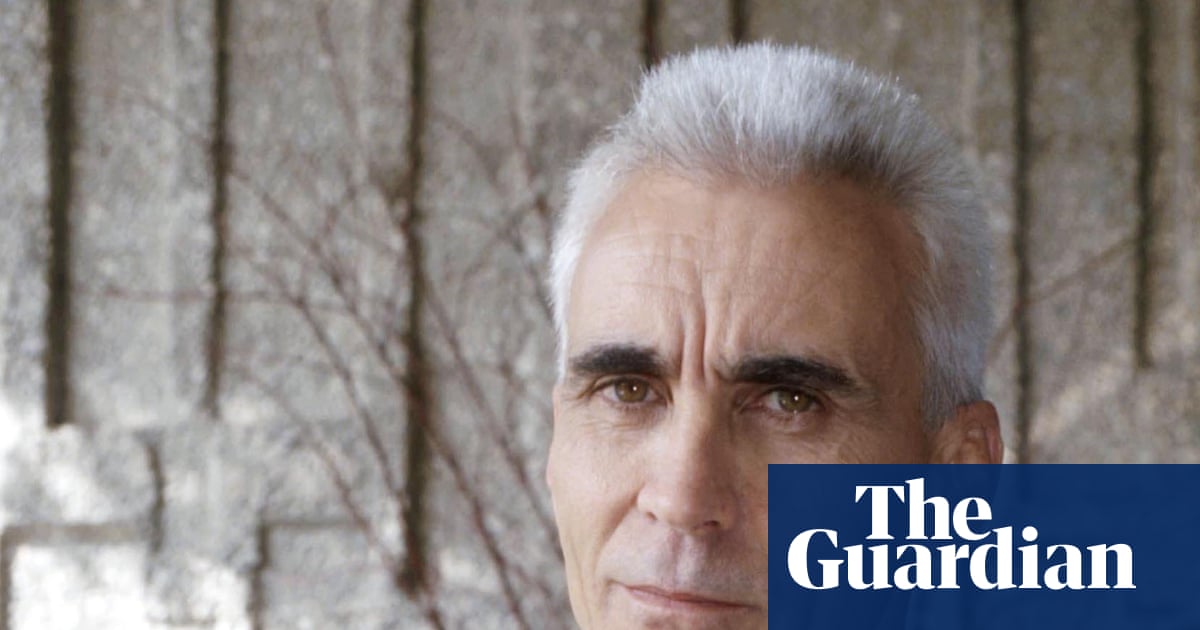

The late broadcaster and campaigner Darcus Howe and Tottenham MP Bernie Grant once fell out over a hot-seat discussion on the former’s current affairs programme, The Devil’s Advocate, broadcast on Channel 4. Grant had provoked backlash from the Black press for discussing state-funded “voluntary repatriation” (a return of migrant and migrant descendant groups to their country of heritage) at a fringe event at the Labour party conference in 1993. Provided an opportunity by Howe to walk back on these comments, he doubled down, suggesting that Black people had “no future in Europe”.

Howe viewed Grant’s position as retrograde, and questioned how a British MP could advocate for a future outside Britain. Grant would complain to Channel 4 about the programme, fearing that it had ruined his political career. But it did not. Despite being abandoned by his Black parliamentary colleagues and only finding mixed support against major rebuke, he remained a respected political figure, and Labour MP, until his death in 2000.

The episode is an important reminder of something that used to exist in mainstream British discourse: important Black figures engaging in serious debate on a controversial – even, offensive – subject. Here was a mainstream platform where, gladiator-style, a discussion pertaining to race in Britain could be contested in all its messiness, ferocity and rigour. Where can we find such a space in the mainstream today?

Perhaps if we were still committed to engaging in complex discussions of race, racialisation and Blackness today, with a public audience acting as a democratic mechanism of accountability, Diane Abbott’s comments would have provoked curiosity and real engagement rather than panic and overreaction.

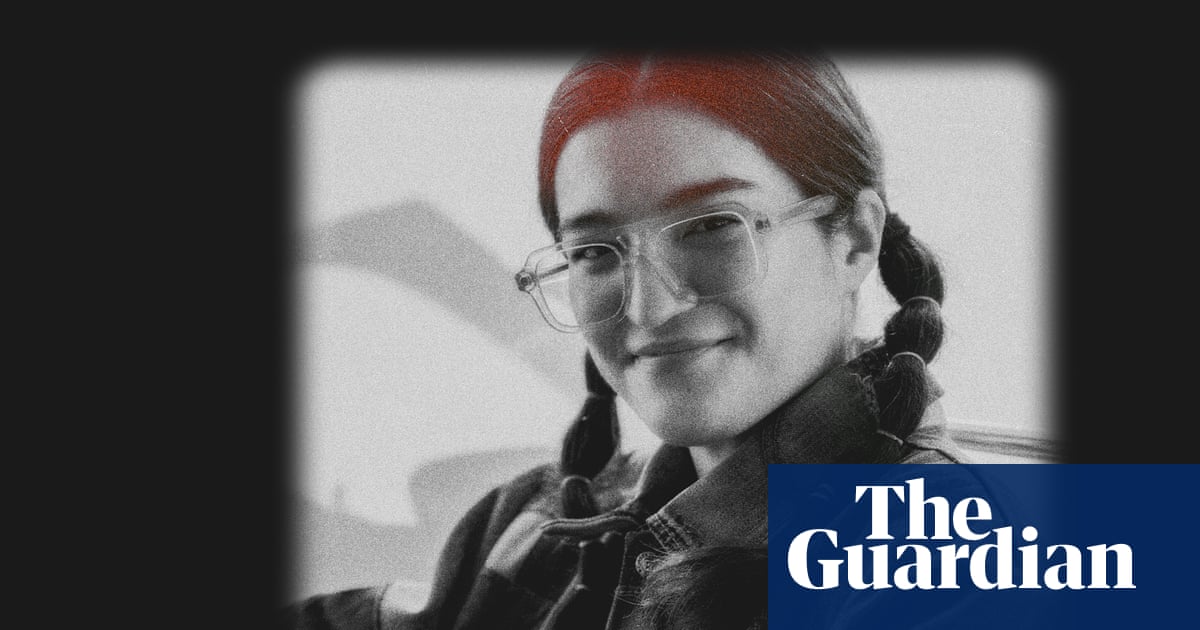

The Labour MP for Hackney North and Stoke Newington, first elected to her seat 38 years ago, was again suspended from the party on Thursday for comments in a BBC Radio 4 interview defending her previously revoked statements around the different experiences of racialisation between certain demographic groups. Where Abbott’s wording in her original letter to the Observer had been clumsy, this time she took the opportunity to clarify what she meant, saying: “Clearly, there must be a difference between racism which is about colour and other types of racism, because you can see a Traveller or a Jewish person walking down the street, you don’t know … but if you see a Black person walking down the street, you see straight away that they’re Black.”

These comments strike me as true. In the same way that while my Blackness is immediately and unambiguously read, my sexuality (I am a gay man) could only be inferred by context, stereotypes or by my own confirmation. Similarly, you may not know that a white person is Irish until you infer it from their name, accent or simply ask them. That does not undermine the reality of anti-Irish (or antisemitic or anti-Traveller) discrimination, and yet it is plainly not the same as what can be visibly deduced before any kind of identifying context is introduced. But even if you disagree with these comments, as you may, why are they so unsayable to the point that Abbott has had the whip suspended? Why, instead, can there not be public discussion on the differing experiences of racialisation, even if they are provocative?

In part, this is down to the decline of serious engagement with Black intellectual thought. Howe’s programme had its cheap moments. And yet in the mid-1990s you could turn on your television and witness thought-provoking debates around race without participants expecting to be served their P45. Equally, you might have been more used to the presence of Black intellectuals on television and radio – the likes of Stuart Hall and CLR James, who had their own interview broadcast on Channel 4 in the 1980s where they discussed, among other things, the Gold Coast revolution and James’s Trotskyism. It is not that such intellectuals or their works no longer exist, but that they are undervalued or treated more tokenistically.

Now, where Black academics and thinkers are called to discuss matters of race, they are largely reduced to shouting matches with the likes of Piers Morgan, with the preferred topics being culture-war fodder around the permissibility of praising Winston Churchill, or the latest development on Meghan Markle. No wonder when faced with a real, considered and provocative attempt to parse race and racialisation, the channels simply shut down. The warning signs for this decline were there: when Howe was interviewed by the BBC to discuss the 2011 riots, the anchor erroneously suggested that he had a history of rioting, to which he responded “Have some respect for an old West Indian Negro.”

The clearest problem, to me, is that there is a lack of interest in the diversity of what Black people think, and how to respond when that may present a challenge. The Labour party has a persistent problem with it – and that includes when the MP Rupa Huq described the former Conservative chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng as “superficially” Black. Patronising and opportunistic as ever, Keir Starmer, after failed attempts to deselect Abbott, praised her as a “trailblazer” upon becoming mother of the House following her re-election. Yet it is a safe conclusion that he has absolutely no interest in what she thinks or says. The same is true of Baroness Lawrence, whom he was all too happy to wheel out in the interests of campaigning, only to face accusations that he was not listening to her when she attempted to engage in dialogue about anti-Black racism.

Our public discussions on race are utterly impoverished, and this is largely because our haughty institutions have developed a preference to either run scared or dismiss real discourse rather than challenge, engage and understand. If the answer to Britain’s first Black female MP parsing the lived experience of racism is to suspend her and confect another political controversy, then the message is that you may not ever say anything difficult at all.

-

Jason Okundaye is an assistant newsletter editor and writer at the Guardian. He edits The Long Wave newsletter and is the author of Revolutionary Acts: Love & Brotherhood in Black Gay Britain

-

Do you have an opinion on the issues raised in this article? If you would like to submit a response of up to 300 words by email to be considered for publication in our letters section, please click here.

3 months ago

96

3 months ago

96