Like all love triangles, Celine Song’s new film Materialists places you at a fateful fork in the road, peering at two points in the distance and evaluating the different futures that lie in wait. In Materialists, the first destination looks like this: a glossy Manhattan penthouse; regular dinner dates at five-star restaurants; few if no apparent friends; a lot of money, and being the object of envy of New York’s society women. What you lack in warmth you make up for in status. The second, meanwhile, is much less glamorous: a dingy shared apartment in south Brooklyn with two slob flatmates; arguments about money; takeaway meals from food trucks. But perhaps you’d have a lot more fun.

It’s the question driving many of our romantic stories, the choice animating everything from Jane Austen’s novels to the climax of reality television show The Bachelor: love or money? Song’s films seem to be more interested in love. Her first feature, the double Oscar nominated Past Lives, was a wistful story about star-crossed love that brought audiences to tears. There is a lot less wist in this follow-up, a satire-tinged drama about the indignities of modern dating in our renewed gilded age. Dakota Johnson plays Lucy, an unapologetic materialist and high-end matchmaker who is instantly charmed by Harry (Pedro Pascal), a banker who is what those in her business call a “unicorn”: rich, tall, handsome, smart. At the same time, she reconnects with ex-boyfriend John (Chris Evans), who still looks at her with a puppy-eyed devotion and nurses his inability to provide her the life she wants like a sore wound.

Except for John, the film’s characters tend to talk to each other with the performative coldness of businesspeople. Potential partners are evaluated for their ability to make one feel “valuable”. Harry declares an interest in Lucy’s “immaterial assets”. Lucy’s clients demand their dates have a minimum salary (the women) or a maximum age (the men). Everybody speaks as if they are angling themselves as contestants on The Apprentice, without any of the messily fun theatrics of reality TV.

The marketing of Materialists has placed the film firmly in the elevated world of Harry’s penthouse over John’s grungy flat. There is the cast, drawn from the most in-demand stars in Hollywood; there is its cult US distributor, A24; there is Song’s “syllabus” for the film, replete with the works of Mike Leigh and Merchant Ivory and Martin Scorsese; the understated, quiet luxury wardrobe; the soundtrack featuring the Velvet Underground and Cat Power. Though when I watched it, I thought not so much of Leigh, but rather the less cool big-budget 2000s romcoms that also set out the same fundamental premise of Materialists: an ambitious young woman tries to make it in the big city, makes mistakes in love and in work, and learns hard lessons about life in the process.

Two decades have passed since these films – How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days, Bridget Jones’s Diary, Maid in Manhattan – commanded the box office, and a lot has changed since, not least the collapse of the blockbuster romcom film and the genre’s move to low-budget fare on the streamers. It’s interesting, still, to see how Materialists has reengaged with the genre’s tropes. It struck me, for example, that John – an avatar of unconditional devotion, unfailingly loyal if a void of any edge – is a Duckie from Pretty in Pink kind of figure, the prospective love interest the protagonist considers before choosing someone more alpha and more interesting (in effect, a Harry). Perhaps after the post-#MeToo reckoning and the ongoing crisis in masculinity, our view of the ideal man has softened – though it helps, I imagine, if the man in question looks like Chris Evans.

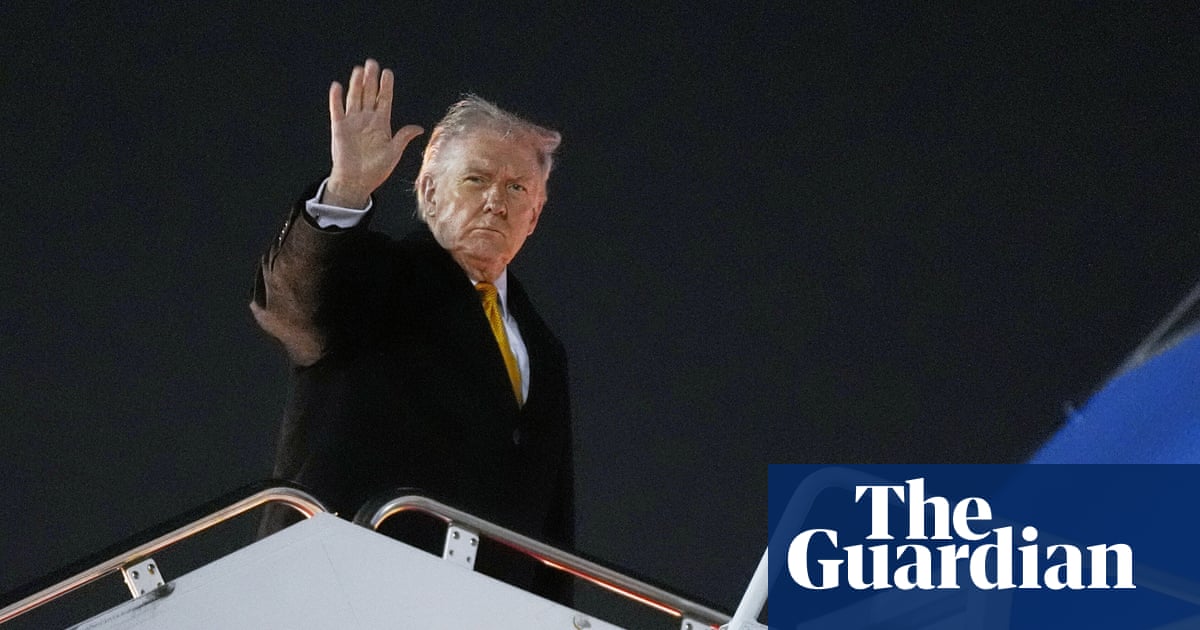

Meanwhile, the film’s affect of extremely mannered and self-aware cynicism seems firmly out of our current age rather than the cheery turn-of-the-millennium sugariness of, say, Love Actually. The world has hardened since, our lives are angrier and more isolated. The internet has sharpened individualist hustle culture, and the most powerful man in the world is a status-obsessed dealmaker incapable of seeing anything beyond the lens of his own ego. And so the characters of Materialists scramble to ascend the marketplace, keeping an eye on where they stand in the pecking order. In today’s US, the bottom can be a terrifying place.

Watching these largely rich, largely lonely people talk about love through the language of the market, I thought: what a sad way to see other people, and what a sad way to be. The film thinks this, too, judging from (spoiler warning!) its sudden about-turn ending, in which love wins over money and the heart triumphs over cold, calculating reason. It is a conventional fairytale romcom ending, but perhaps with everything that’s passed since, this retro callback is the point: a bid for a new sincerity after decades of status-conscious cynical individualism. Duckie has finally won over the rich alpha male; the biggest prize today is someone who will love you unconditionally.

I didn’t find this final triumph in Materialists particularly convincing: its characters were too cold, too unspecific and lacking in vitality to really make me root for their final reconciliation. (I did appreciate, though, the film’s contemporary twist on the romcom fantasy: Lucy’s realisation that her dream job is ethically murky and of indeterminate value to the world.) But it did make me want to see more romcoms on the big screen, ones with intellectual curiosity and seriousness that command the space that Materialists – against prevailing movie industry trends – has been given. The beauty of love, after all, is that it can break through our solipsism and radically reshape ourselves. It is a hopeful, radical practice that finds in other people not cause for anger, defence, or hatred, but possibility for mutual wisdom and growth.

“The whole movie is about fighting the way that capitalism is trying to colonise our hearts and colonise love,” Song said recently. Maybe finding space for life outside capitalism’s relentless onward march is increasingly a fantasy – but what a beautiful, frothy fantasy that can be.

2 months ago

89

2 months ago

89