‘Punjabi Disco is the holy grail of British Asian music,” DJ and label boss Raghav Mani says. “It’s a miracle this record exists. For decades it has been lost to the world, but now we can hear it in all its glory – the album that birthed the British Asian dancefloor.”

Recorded in London in 1982, the nine-track album combines producer Kuljit Bhamra’s searing synthesiser melodies and hammering drum machine rhythms with the Punjabi-language folk singing of his classically trained mother, Mohinder Kaur Bhamra. Part early acid house experiment, part north Indian tradition and part disco-funk, the record was a futuristic outlier: the south Asian fusion sounds of bhangra were only just beginning; the mainstream crossover music of the Asian underground was more than a decade away; and the British Asian diaspora were largely relegated to meeting at weddings and community events, rather than at the disco.

Limited to only 500 copies, Punjabi Disco disappeared from circulation almost as quickly as it was released, leaving Mohinder to go back to singing at Sikh weddings and Kuljit to producing bhangra records by groups such as Heera. In the decades since, rare copies have materialised online for thousands of dollars but it has otherwise vanished into obscurity. That was until Mani stumbled on a new lead.

“When you’re a record collector you can develop this jaded feeling that you’ve seen and heard everything,” he says. “Except, in 2022 my friend Massimo called me and was so excited about this new discovery that he had to play it to me over the phone. Even down the line, I could tell it was something singular and indefinable in its sound. He said it was called Punjabi Disco and he had just bought the last copy in existence, directly from Kuljit.”

Mani and his business partner Filip Nikolic immediately decided to see if Kuljit was willing to release a reissue on their archival label Naya Beat. “It was a three-year process, from first hearing the record to Kuljit finding the original master tapes in his house and digitising them before they completely degraded,” Mani says. “During that time, we discovered that not only is it an incredible-sounding album that more people need to hear but it also has a crazy story behind its making.”

Allow Bandcamp content?

This article includes content provided by Bandcamp. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. To view this content, click 'Allow and continue'.

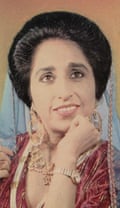

Moving to London in the early 1960s, after a childhood spent in India, Uganda and Kenya, Mohinder built a reputation as a spiritual singer. She was the first woman in her community to sing at local Sikh gurdwara events and progressed to performing at wedding receptions. Her family provided instrumental backing, including Kuljit who accompanied on tabla from the age of six.

As the 1970s approached, though, Mohinder began to be uncomfortable about the gender segregation she witnessed in the crowd. “South Asians weren’t living in England in large numbers and they faced a lot of racism, so there weren’t many places for them to gather,” she says. “One of the few spaces they could enjoy themselves were wedding receptions, but every time we would get up to sing, the women would typically be in another room and only the men were allowed to dance. I felt it wasn’t fair and so I started to invite them in.”

after newsletter promotion

By the new decade, Mohinder and the Bhamra family band had become notorious for enabling the first mixed British Asian dancefloors and the songs in their repertoire began to change to suit their crowd. “There was one guy who dressed like an Indian Elvis who used to crash the weddings to watch us play. If we could get him moving, I knew we were on to something,” Kuljit laughs. “By the time Saturday Night Fever came out in 1978, disco mania was happening and I could see people in the crowd even more eager to dance. I decided we should write our own music to reflect that.”

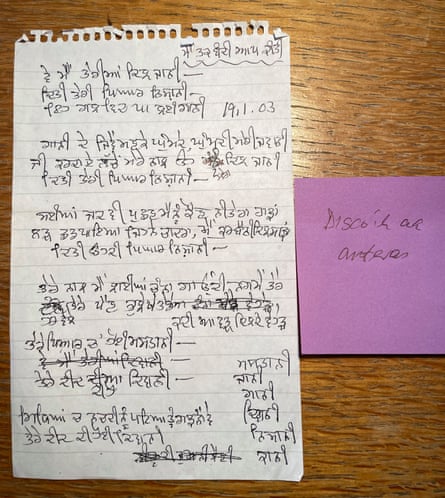

Armed with Roland’s first synthesiser, the SH-1000, 22-year-old Kuljit began recording demos on reel-to-reel tape that he would share with his mother at the kitchen table every evening. She wrote her own lyrics to the beats, finding an aptitude for penning yearning romance narratives. Soon Kuljit had enough material for the record. He booked a local studio, which happened to be run by Roxy Music’s bass player Rik Kenton and, along with his mother, 11-year-old brother Ambi on the drum machine and bass-playing friend Trevor Michael Georges, they laid down the tracks. “It was a joy to record as everything just clicked,” Kuljit says. “I always treated my mother’s voice as an instrument, like a flute or keyboard, so the sound of the record was really cohesive while also feeling totally new. We thought people would love it.”

Yet, months after being told by executives at EMI India that the record would be released, the family stumbled upon a cassette with the title Punjabi Disco being sold in a Southall record shop, featuring a different singer and new songs. Kuljit saw it as a direct theft of their idea. “We were devastated,” he says. “We managed to argue our case and got a distribution deal but they only pressed 500 copies that we barely saw. I actually ended up biking copies of the few records they gave us to local cornershops to see if they might shift some there!”

It wasn’t until Kuljit was approached by Mani that he went looking for the master tapes again and even discovered a new unreleased track, the rollicking disco-funk number Dohai Ni Dohai, which wouldn’t fit on to the original 12-inch pressing. “It was all made to get people dancing and the tragedy is that we never got to play it live after it was recorded,” Kuljit says. “Since it’s now been remastered and remixed, a new generation can finally enjoy it for its original purpose, while my mum can get her dues for being such a radical.”

“It’s incredibly brave for first- and second-generation migrants to make an album like this that breaks all conventions, especially in the context of the era’s racism and sexism,” Mani adds. “Mohinder is very traditional in many ways and an expert Punjabi folk singer but she’s also an advocate for women’s rights – she doesn’t fit into an easy category and neither does her music.”

Now 89, Mohinder is no longer performing but she is happy to hear herself once more. “I was young and my voice sounds good,” she laughs. “I’m proud of what my boys achieved and I hope people can enjoy and move to this music again.”

Punjabi Disco is out on 31 October on Naya Beat Records.

3 months ago

90

3 months ago

90