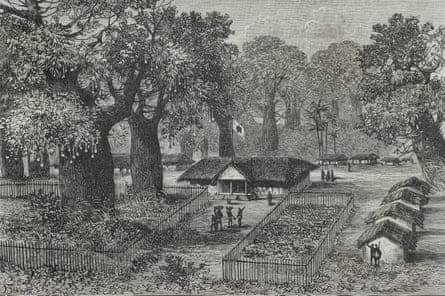

The older inhabitants of Kinshasa can remember when trees shaded its main avenues and thick-trunked baobabs stood in front of government offices.

Jean Mangalibi, 60, from his plant nursery tucked among grey tower blocks, says the capital of the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s frenzied expansion has all but erased its greenery. “We’re destroying the city,” he says, over the sound of drilling from a nearby building site.

The number of trees lost in and around this vast city, the third largest in Africa, has made it all the more urgent for environmentalists to campaign to protect one of its last – and most notable. A single century-old baobab tree remains standing in the historic centre of Kinshasa – in the commune of Gombe – but it too is now under threat. Mangalibi and like-minded activists are rallying to save the symbol of the city’s past from developers.

“It’s part of the soul of Kinshasa,” he says. “We have a responsibility to protect it.”

Kinshasa, with an estimated population of 17.8 million people, half of them aged under 22, was mostly built in the first half of the 20th century, during the murderous reign of the Belgian colonialists, as a planned modernist capital, strategically sited on the Congo River.

But breakneck growth and nonexistent urban planning have created one of the world’s fastest-growing – and notoriously polluted – megacities. Flooding regularly claims dozens of lives and sends waves of plastic waste through poor neighbourhoods.

The baobab stands on a plot of land next to the main ferry port, owned by the DRC’s state-owned transport company, Onatra. Until last year, a popular fabric market was centred on the old tree.

But the site is now closed off and the first signs of building work are visible. Activists and local government officials accuse Onatra of selling the land to a private developer. It is not clear who is involved, and Onatra did not respond to the Guardian’s questions.

In August, diggers arrived at the site, prompting Mangalibi and other activists to turn up and block the construction work, saving the tree just in time, says Sifa Kitenge, a fabric trader who worked under the baobab. “They were ready to cut it down,” adds the 70-year-old, calling the baobab “an important symbol”.

The tree remains standing for now, but the construction work has not been abandoned, raising fears for its future.

Kinshasa’s last baobab carries rich symbolic meaning, as do baobabs across Africa. The majestic trees have great value as a source of food in their fruit and leaves – and as symbolic places for meetings and speeches. With their stature and great age, they represent a link to the past too.

Local tradition holds that British-American explorer Sir Henry Morton Stanley negotiated land from traditional chiefs under a baobab in the 1870s, marking the beginning of the colonial settlement in Kinshasa.

“It’s a continuation of history,” says Mangalibi, who adds this baobab is more than a century old, and was planted to commemorate the building of the ferry port.

Such commemoration trees were once common, but disappeared along with other greenery as the city grew.

In 2010, the city authorities chopped down hundreds of leafy terminalia trees that lined Kinshasa’s main artery, the eight-lane Boulevard du 30 Juin. Officials promised to replant them, but the boulevard remains bare to this day.

Francis Lelo Nzusi, a geographer at the University of Kinshasa, blames a lack of planning, but also on the constant need for fuel. Only 41% of people in Kinshasa have electricity, meaning millions rely on charcoal for cooking – trees chopped down for charcoal are rarely replanted.

“Everything has been cut down,” says Nzusi. Planned green spaces also quickly become fly-tips, he adds, since there is no proper waste-management system.

Demographic pressure in Kinshasa is intense – the population grows by about 730,000 people a year. Much of the endless city sprawl consists of cramped concrete houses clustered along unpaved, flood-prone alleys. Larger roads are clogged with traffic and impromptu markets.

Against this background, Jean Mangalibi has started a pressure group with other activists, called Autour du Baobab, or Around the Baobab. The group is focused on saving the last baobab through lobbying and public events, but the activists also plan to tackle other environmental issues.

“It’s work that carries a lot of risk,” says Mangalibi, whose nursery has been ransacked several times due to his activism.

This time, however, he has some government officials on his side. Malicka Mukubu, the head of the DRC’s National Tourism Office, said the baobab must be saved because it represents the strength of Congolese culture. “From an ancestral point of view, you don’t cut down baobabs,” says Mukubu. But the challenge is steep, she admits, not least because most public officials are indifferent.

1 day ago

12

1 day ago

12