As a child growing up in Edinburgh, I was taught this was a city built on the genius of the Scottish Enlightenment. That story was sunk deep into our bones and passed between us as our treasured inheritance. It formed our sense of ourselves and our belief in Scotland’s good and worthy contribution to the world.

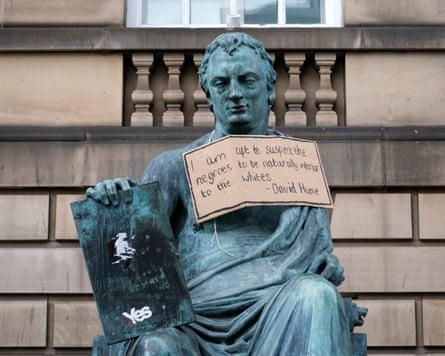

We walked past statues of David Hume and Adam Smith. We celebrated their intellect and claimed it as our own. Yet no one spoke of what lay beneath that brilliance – of whose labour built their wealth, whose bodies were stolen, dispossessed and abused as a consequence of their “thinking”. Edinburgh was framed not as a city of complicity but of genius. That silence shaped us.

Now, the University of Edinburgh’s review of its legacies of enslavement and colonialism joins a wider reckoning that has been building across Scotland. It confronts the stories we were told – that we continue to tell. That we love to tell.

Scotland has long positioned itself as a nation on the margins of empire. We speak of being oppressed, victimised – or as a benign participant in the British imperial project. But many of us, through our family histories, have always known that’s not the whole truth. It’s a lie of omission. One that has excluded us, exiled us from a national story in which we also have histories to contribute, and in which we have a claim.

Edinburgh University’s recent inquiry into its history is sobering. It focuses on the institution’s financial gains from plantation slavery, its intellectual support of racial pseudoscience and its memorialisation of colonial figures. It names how Enlightenment thinking in Scotland justified racial hierarchies. These aren’t revelations for many Black and Brown Scots, or for those involved with Scotland’s anti-racism movements – they’re confirmations of truths long lived and denied.

And still, we are met with denial, minimisation and the defensive recoil of a nation uncomfortable with the truth of itself. There’s a reflex to preserve pride at all costs within our society – even when the cost is exclusion and erasure of fellow Scots; of their histories and their story of Scotland.

The work of uncovering Scotland’s pivotal role in enslavement and colonialism has been led by individuals such as the academics Geoff Palmer and Stephen Mullen, Zandra Yeaman at the Hunterian Museum, Lisa Williams, founder of the Edinburgh Black History Walk, and the poet Shasta Hanif Ali, who explores the stories of the Indian ayahs who lived and worked in Edinburgh. Their work has helped us understand long-denied histories and given many of us a stronger sense of belonging as a result. The University of Edinburgh’s report adds further weight to their labour. But what comes next?

Race is a social construct. But we must now confront the fact that it was constructed, in part, here, by so-called “great men” – our great men – whose legacy continues to shape our country and institutions. And their legacy still causes us harm.

This harm is not abstract. In 2024 alone, Police Scotland recorded 4,794 hate crimes under the new Hate Crime and Public Order (Scotland) Act. Black and minority ethnic people are 60% more likely to live in the most deprived parts of Scotland than their white counterparts. Black and minority ethnic workers have poorer outcomes than white workers when applying for jobs in our public sector organisations.

These are reverberations of a legacy born in Enlightenment philosophies that theorised racial hierarchies – ideas presented as science, later used to justify enslavement and colonialism. These narratives of white supremacy negatively affect us all, and they continue to endanger and blight the lives of Black and Brown people.

What happens next must therefore go beyond apology and symbolism. It must be structural, sustained and fiercely imaginative. Education is key. Not just to correct the record, but to transform how we imagine and create a better nation. Within our schools, reform is under way – initiatives such as Education Scotland’s Building Racial Literacy programme and collectives such as The Anti-Racist Educator provide vital resources and training.

Such efforts must be scaled, funded and politically backed if they’re to meaningfully reshape how we understand ourselves, how we embed anti-racism within our institutions and how we teach Scotland’s history.

Edinburgh council’s Slavery and Colonialism Legacy Review, endorsed by councillors in 2022, included a public apology and the creation of an implementation group, chaired by Irene Mosota, to guide reparative action. This included initiatives such as the Disrupting the Narrative project, which has formed the main body of my work as Edinburgh makar (the city’s poet laureate). The meetings of the Scottish BPOC Writers Network’s writers group at the University of Edinburgh, and the important work of mentorship and support from We Are Here Scotland are also living examples of this reparative work. This work is not symbolic – it is foundational. It allow us to rebuild from the margins, and write ourselves back into the story of Scotland, and into the story we tell.

This is a live, unfinished conversation – one that must embrace intersectionality, mobilise solidarity and resist the far right’s weaponisation of pseudoscience and historical denial. Opposition to anti-racism is often framed as resistance to “political correctness”, and calls for decolonisation are frequently mocked or deliberately misunderstood. Silence, however, is complicity.

History is not settled. Our story is not finished. We are capable of confronting ourselves honestly and critically. We can take pride in our history of social justice movements – but this pride must also own and acknowledge the truth of what and who built this nation. That means interrogating our past and the reasons for our collective amnesia. It means listening to voices long silenced. The time has come, Scotland. The time has finally come.

-

Hannah Lavery is a Scottish poet and playwright. She will be appearing in Disrupting the Narrative – a Performance, at the Edinburgh international book festival

-

Do you have an opinion on the issues raised in this article? If you would like to submit a response of up to 300 words by email to be considered for publication in our letters section, please click here.

3 months ago

163

3 months ago

163