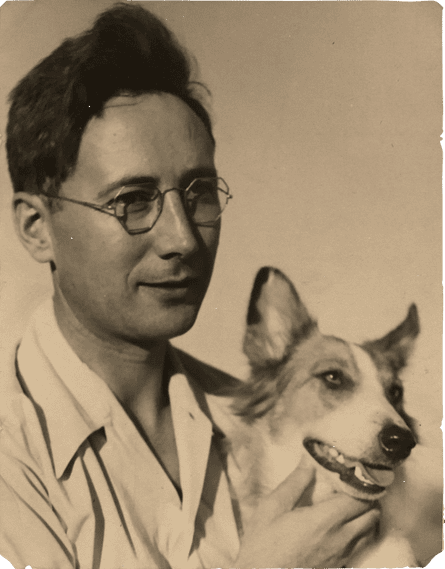

In 1913, on a remote, windswept stretch of buffalo-grass prairie in western North Dakota, Roald Peterson was born – the ninth of 11 children to hardy Norwegian homesteaders.

The child fell in love with the ecosystem he was born into. It was a landscape as awe-inspiring and expansive as the ocean, with hawks riding sage-scented winds by day and the Milky Way glowing at night.

As a young adult, he decided to study the emerging field of range science in college, which led him to Louisiana – where he was so appalled by the harsh conditions faced by sharecroppers that he volunteered with a farmers’ union. After serving stateside in the army air forces during the second world war, he took a job in Montana with the US Forest Service, monitoring cattle and sheep grazing on public lands. He took to his work with high morale.

Unfortunately for Peterson, his career took off at the height of anti-communist hysteria, at which time the second red scare, also known as the McCarthy era, was well under way.

In the midst of this culture war, Peterson’s environmental advocacy and concern for exploited workers made him a glaring target, a man with a bullseye on his back. In 1949, two anonymous informants falsely accused Peterson of having been a communist, setting off an invasive loyalty investigation.

Montanans from across the political spectrum rallied to his defense. So did the Pulitzer Prize-winning historian and conservationist Bernard DeVoto, who was so moved by the case that he penned the most controversial column of his 20-year run at Harper’s Magazine: Due Notice to the FBI.

In it, DeVoto delivered a bold defense of civil liberties in the face of growing authoritarianism – one of the earliest national articles to openly criticize both FBI director J Edgar Hoover and senator Joseph McCarthy.

As the red scare escalated, Peterson’s loyalty was investigated a second time, and then a third when another informant told the FBI he was “behaving like a homosexual”.

Peterson was fired from the Forest Service in early 1953. He lost his family’s ranch in Montana’s Bitterroot valley (not far from where the show Yellowstone is filmed). Peterson’s wife left him and was committed by her family to an asylum. A judge awarded custody of his three children to the state, placing them in foster care.

A granddaughter, whom I located and interviewed, told me the children were repeatedly sexually abused; the two youngest later died by suicide.

Peterson’s 2004 obituary, penned by his surviving daughter, states that he was “blacklisted by the infamous Joe McCarthy, Roy Cohn and J Edgar Hoover group of legal thugs”.

That the one in the middle was Donald Trump’s mentor underscores the connection between then and now.

Peterson was targeted during a low chapter in American history – one that feels eerily familiar today.

It was a time when reactionaries in Congress plotted to sell off public lands – just as they do now. When the US Forest Service was under intense pressure to clear-cut more trees – just as it is now. When public lands faced destruction in the name of energy production – just as they do now. More than 14,000 people were forced out of government jobs during the red scare – a mass purge that mirrors the targeted layoffs we’re witnessing now.

Meanwhile, the Trump administration has made no secret of its ambitions: a ramp-up of logging and drilling across public lands, and a sweeping plan to shrink up to six national monuments in the south-west.

Taken together, a larger strategy comes into focus: Republicans are laying the groundwork to sell off some of the nation’s most treasured public assets. And it begins with gutting the numbers and the morale of the very people who protect them.

Bill Wade boasts nine decades of perspective on the US’s public lands. The son of a ranger, the 84-year-old was raised inside Mesa Verde national park in Colorado and went on to have a long career in the agency, eventually serving as supervisor at Shenandoah national park in Virginia.

Now retired, Wade serves as the executive director of the Association of National Park Rangers, which makes him an excellent ear to have on the ground. He has a bracing take on conservation workers and our public lands.

Morale, he says, is probably the lowest he’s seen in his 58-year career.

That’s a reasonable take, given that the message from the Trump administration is, to paraphrase the novelty slogan: “Purging will continue until morale improves.”

February 2025 brought the “Valentine’s Day massacre”, when the misnamed “department of government efficiency” fired 1,000 National Park Service employees and 3,400 from the US Forest Service. In March, courts ruled the firings lawless. More buyouts followed. In May, the administration signaled it would slash the agency’s budget by 40% – the biggest cut in its 109-year history.

With parks having boasted record visitation in 2024, this year they are already reporting shortages in visitor center hours; campground accessibility; sanitation; interpretation, such as ranger-led hikes; and environmental stewardship, such as trail maintenance and wildfire prevention programs with youth conservation volunteers.

None of the personnel cuts make good business sense. The National Park Service oversees resources that cost $3.5bn annually to manage, yet generate more than $55bn in revenue. Protecting such a profitable national asset should be a no-brainer. Despite that, conservation workers have been in effect barred from buying new supplies costing more than $1.

Already, the National Park Service has about one employee for every 17,000 visitors, said Timothy Whitehouse, the executive director of Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility. “They’re breaking the system,” he said. “They’re traumatizing the workforce.” Many worry about the brain drain that will follow.

That younger generation’s malaise was touched on in a poignant letter by the US Forest Service chief, Randy Moore, who announced his resignation in March. “If you are feeling uncertainty, frustration or loss, you are not alone,” Moore wrote. “These are real and valid emotions that I am feeling, too. Please take care of yourselves and each other.”

Read between the lines: I understand the damage this all does to morale.

His leaving was conspicuous, coming at the start of Trump’s anti-diversity zealotry. Moore is the first Black person to lead the forest service. Was his replacement, Tom Schultz, chosen because he is the same race as every other chief in the service’s 116-year history? Or because the former timber industry executive is the first chief never to have served in the forest service? (Or both?)

Whitehouse explained that it wasn’t just that the conservation workers were fired, it was how they were fired: the dismissed employees had received a form letter which stated that they “failed to demonstrate fitness or qualifications for continued employment”.

Conservation workers deal in hard, natural truths: the forest is on fire, the river is in flood, the bear is there. The “failed to demonstrate fitness” letters are false by any degree of objective measurement.

Wade, the experienced ranger, described it with a phrase used for totalitarian propaganda.

“All of this amounted to,” he said, “a big lie.”

We have been here before.

The question goes, why are there public lands? Why protect them?

The start of the answer is put nowhere better than the Bible. Genesis, 2:10:

And a river went out of Eden to water the garden …

When Europeans reached the eastern shores of North America, they found a climate with rain amounts similar to the lands they had left. Land ownership in Europe was feudal, with kings and lords controlling vast expanses. In democratic opposition, Americans distributed small farms and plantations to a far wider array of its citizenry.

As the nation expanded westward from the original 13 colonies, Thomas Jefferson maneuvered the public domain into the control of the federal government, so states would not war with each other over land.

So far as the rainfall remained similar to Europe, this American settlement system was tenable. But when settlers crossed the Mississippi River in the 1800s, they confronted a new climate: desert.

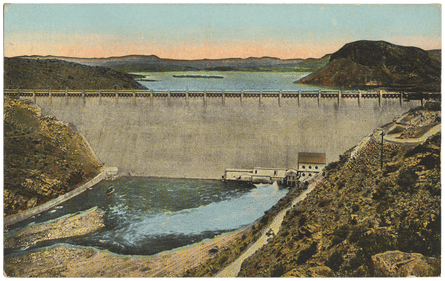

Across vast expanses of the US west, the majority of the precipitation collects as wintertime snow on the tops of high mountains. As was figured out by the ancestral Puebloans, who irrigated farmland and built towns and cities in the American south-west for centuries before Columbus sailed, the key to survival is getting the summertime meltwater from mountain snowpack safely and cleanly down into the valleys where lie the farms, ranches, towns and cities.

For this to happen – for our national garden to be watered – there must be healthy mountain forests and grasslands. These mountains and prairies, the vast majority of which were never claimed by homesteaders and never belonged to any state, would become the bedrock of public lands conservation.

It is a wonderful fact of nature that some of the most magnificent scenery is where rivers begin: at the tops of mountain ranges. This is why our awe-inspiring national parks – Yosemite, Yellowstone – became the modern world’s first protected public lands. It’s always worth remembering the words of writer Wallace Stegner: national parks are America’s best idea.

But national parks proved far too small to protect all the water the dry west needs. At the turn of the 20th century, President Theodore Roosevelt made the US the first modern nation to enshrine public lands conservation as a national priority. He created 150 national forests in the west to ensure a consistent supply of water and timber. Soon followed the first national wildlife refuges and the first national monuments.

Protecting only parks and forests proved tragically insufficient. Come the 1930s, farmers over-plowing dry prairies and deserts caused the Dust Bowl – the worst single-event environmental disaster yet in the nation’s history. To protect the soil-saving, deep-rooted native grasses, in the 1930s President Franklin Roosevelt created the Grazing Service. The protection of grasslands, prairies, deserts and canyonlands heralded a completeness of conserved landscapes.

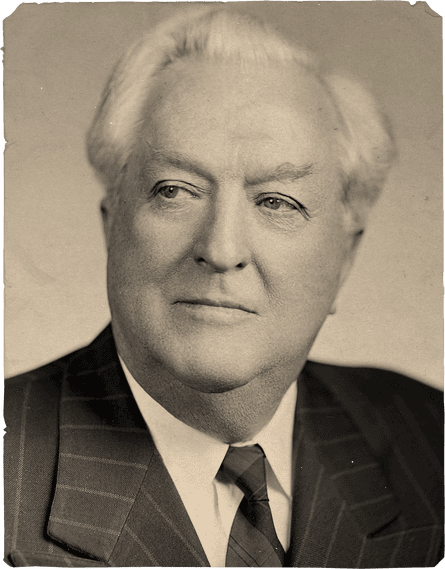

The counterattack to undo public lands conservation began at that point. By the 1940s, some western cattle kings and sheep barons, historically used to monopolizing western ranges, attacked the Grazing Service. Their tool was the Nevada senator Pat McCarran – a role model for senator McCarthy. McCarran toured the US west staging hearings about public lands in which he brazenly gave priority and preference to cattle kings and sheep barons.

A McCarran aide explained that a purpose of these hearings was to affect conservation workers “psychologically” – to hurt their morale. McCarran would order employees to attend his hearings and forbid them to speak, while encouraging his curated audiences to shout insults at them.

Mass layoffs followed – similar to the purge we saw this February. Disparaged and defunded, the service was amalgamated in 1946 into a new, enfeebled and industry-friendly agency called the Bureau of Land Management.

The political exploitation of fear, paranoia, conspiracy, false accusations, show trials, refusal of fair play and apocalypticism could be called McCarranism as accurately as McCarthyism.

McCarran’s work still fills our headlines today: it was he who legalized peacetime concentration camps in the case that the president declares an emergency – which Trump does frequently. And it was he, over President Harry Truman’s veto, who passed the 1952 law that Trump is using to jail foreign-born students without arrest warrants.

If history offers any hope, it may be worth looking at what happened after McCarthy was shamed off the national stage.

In the 1960s and early 1970s came an American renaissance in conservation, and with it the passage of historic environmental legislation. With broad, bipartisan support came laws like the Clean Air Act, the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, the Wilderness Act and the Endangered Species Act.

Federal conservation workers today may prove as resilient as those who withstood the red scare – who themselves proudly showed they had the same tenacity and psychological toughness as their forebears in other times of national duress.

We only have to look back in time to see plenty of examples. In 1910, the forest service was in its infancy when its understaffed and under-equipped employees battled a deadly Northern Rocky Mountains forest fire as big as the state of Connecticut.

In earlier decades, members of the army’s famous all-Black cavalry, the “Buffalo soldiers”, showed the mettle to protect western national parks through an era of resurgent white supremacy.

During the Great Depression, Franklin Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps put more than 3 million poor, jobless and hungry young men to work planting 3bn trees. The morale and spirit they developed in those hard times is reflected in the unofficial motto they developed: “We can take it!”

But we are also running out of time. Trees take centuries to grow, ecosystems take millennia to congeal, and this climate is the only livable one humankind has ever known. An unmerciful fact about public lands is, like some store signs say: all sales are final.

A few years after Peterson was fired, his case was re-examined; he was found never to have joined the Communist party. He was offered his old job back.

Because of the way he had been treated, he refused. They had broken his morale.

This is the point of what is going on. At stake is our Eden. The Bible also has a story about what happens if we lose that.

-

Nate Schweber is a journalist and the author of This America of Ours: Bernard and Avis DeVoto and the Forgotten Fight to Save the Wild

5 hours ago

7

5 hours ago

7