British scientists are “over the moon” to be back in the EU’s flagship science research programme Horizon after a three-year Brexit lockout, with new data revealing they have been awarded about £500m in grants since re-entry.

As the EU secretly draws up strategies for the next seven-year funding cycle in 2027, the UK is hoping its success in the first 12 months since returning to Horizon will leave it in pole position with Germany and France to dominate European science, despite Brexit.

With projects ranging from the research to develop brain catheters inspired by wasps to efforts to create aviation fuel from yeast and greenhouse gases, the UK has been catapulted to the top of the league of non-EU beneficiaries by number of grants. And, at fifth position behind Germany, Spain, the Netherlands and France, it looks set to resume its overall place in the coming 12 months.

EU data shows nearly 3,000 grants were awarded to British science projects in 2024, the first year of the UK’s post-Brexit associate membership after a three-year pause caused by a Brexit row over Northern Ireland.

“I am absolutely over the moon that we are back in the programme formally,” said Ferdinando Rodriguez y Baena, a professor in medical robotics at Imperial College London.

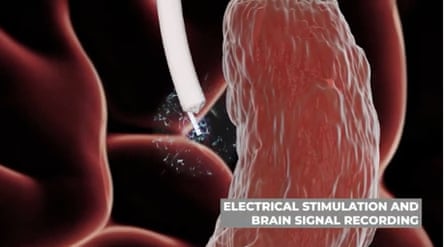

He has recently completed a 15-year Horizon-backed research project inspired by a conversation he had with the renowned zoologist Julian Vincent about the wasp’s wondrous ability to penetrate hard tree bark to lay eggs. Rodriguez decided to try to reinvent that for neurosurgery to create a minuscule cranial catheter to penetrate the skull and deliver drugs or ablations to brain tumours.

Taking stock after the first year back in the £80bn Horizon programme Prof Sir John Aston, the pro-vice-chancellor for research at the University of Cambridge, said he hoped the embargo “never happens again”.

“It is really good that we are back inside the tent,” he said, adding that it showed the world the UK’s commitment to being a “science superpower” with world-class research. “This is really competitive funding, and [it shows] that people who get this funding are doing really impressive work.”

Rodriguez was among those to meet the European trade commissioner, Maroš Šefčovič, on a visit to Imperial on Wednesday to underline the revived science collaboration with the EU.

“Everybody is delighted,” Rodriguez said. “Everyone is using that opportunity to start thinking with a European hat on about how to leverage these opportunities and reach out to colleagues in continental Europe and so on.”

His €11m (£9.4m) Eden2020 research to develop the cranial catheter was driven by an €8m grant for a consortium led by Imperial but involving a hospital and two universities in Italy along with universities in Germany and the Netherlands.

The UK’s isolation was a “double whammy” to science, Rodriguez said, because he had stopped applying for funding and also collaboration with European partners had weakened. While “academia is porous” and the exchange of ideas had continued, there was “nothing like joint funding to cement a relationship”, he said.

Prof Carsten Welsch, the head of accelerator science at the University of Liverpool, was one of many who implored the government and the EU to allow the UK back into the Horizon programme. The pause cost him his leadership role in a prestigious Marie Curie network on novel plasma accelerators.

Now, Welsch said, the UK was back in the game and a lead participant in the new €10m project to help optimise plasma accelerator-based compact research infrastructures. “We have gone from maintaining presence to driving progress,” he said.

The EU is developing its strategy for the next seven-year funding programme, FP10, which will start in 2027. “It’s all very secretive but it is in full swing and it is important that we position ourselves positively,” said Welsch.

In 2024, 2,911 grants worth €574.7m were awarded to the UK, which had the highest number of beneficiaries of any of the 19 non-EU members in the programme and the third highest by value in just 12 months.

The University of Oxford was the top beneficiary, receiving €42m, followed by Cambridge at €39.3m, and University College London and Imperial with about €28m. The Universities of Warwick and Edinburgh received more than €13m each while other organisations, such as the Royal Veterinary College, were awarded smaller grants of about €275,000. The Met Office received €1.22m.

Fresh calls for funding for space and industry open at the end of May with virtual and augmented reality calls later this year, something Rodriguez is “eagerly” waiting for.

The freeze saw UK-based scientists “bumped off” projects altogether, said Dr Rodrigo Ledesma-Amaro, a bioengineer at Imperial, who is running eight active research programmes with EU grants.

It would have been “catastrophic” if the UK had not been allowed back into the programme, according to Ledesma-Amaro. “We wouldn’t have been able to start new collaborations. It would have been bad for post-doctorate developments, for training and for the exchange of students.”

Ledesma-Amaro’s eight grants centre on sustainable food research, including one project titled the “solar spoon”: this uses energy from the sun to generate hydrogen, which can then be processed using bacteria to generate proteins that can be used for food, he explained. Another centres on delaying “yeast death” to develop biotechnological processes around fermented food, while another is aimed at creating aviation fuel from yeast.

Over at Cambridge, Aston pointed to sustainable fuels research, led by Prof Erwin Reisner, aimed at converting solar energy and renewable electricity and greenhouse gases into sustainable fuels and chemicals.

Reisner met Nick Thomas-Symonds, the UK’s EU relations minister, last month to show the spread of Horizon projects at Cambridge, which also include research into iridescent plant colours and information theory in AI.

“[Horizon] really makes a difference, not just in the academic sense, but these are the technologies that are going to solve some of the world’s big problems,” Aston said.

Cambridge is one of the UK’s best-funded universities but, Aston said, being intertwined again with European universities and private research outfits was vital. “We are incredibly fortunate to be in a university where we have amazing expertise across the university, but we certainly don’t have all expertise,” he said.

7 hours ago

8

7 hours ago

8