It’s the only American radio show that’s been on the air for 100 years, an institution that launched the country music industry as we know it and a stage production that made country fans flock to Nashville in the first place – and keeps them coming for a singular experience today. “I somehow understood the weight of what I was stepping into,” says Marty Stuart of the Grand Ole Opry, specifically the first night he played in 1972 as a mandolin-playing prodigy sitting in with bluegrass star Lester Flatt’s band.

Stuart went on to become a country star, and Opry member, himself, and has now embraced the role of elder on the show: on 26 September, he along with Luke Combs, Darius Rucker, Ashley McBryde and Carly Pearce will take part in the Opry’s first-ever overseas broadcast at the Royal Albert Hall, as part of a year-long 100th birthday celebration. “A hundred years of anything, especially in show business, it’s just unheard of,” he marvels.

It has been a centrepiece in Stuart’s life for most of his 66 years: as a kid in small town Mississippi in the 1960s, he listened to Opry radio broadcasts from Nashville. By the early 90s, he was scoring hits as “a rhinestone-wearin’ country rock’n’roller”, and the Opry’s longtime legends – particularly fiddling balladeer Roy Acuff and comic personality Minnie Pearl – were nearing the end of their lives. Stuart sought their approval: “They had spent their lives building that institution, and I wanted to know that I was on the good side of the line with both of those folks.” Both did give him their blessing, but Pearl made him sweat first. She looked right past the armful of white roses he brought her, critiqued his attire – “Look at those tight pants!” – and admonished him to maintain the Opry’s good image.

He kept the pants, but took her wishes to heart, and the basics of a night at the Opry’s downhome variety show have remained much the same. “It is not, on paper, the makings of a successful show,” laughs Dan Rogers, the Opry’s executive producer.

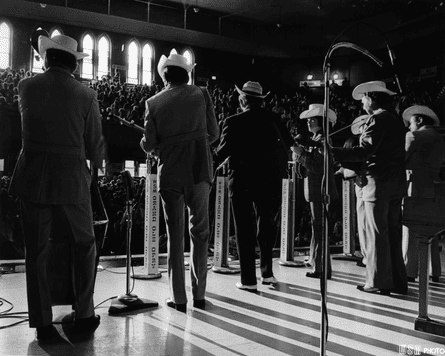

Recorded and broadcast live in front of an audience, announcers project a mixture of folksy intimacy and professionalism as they welcome everyone, read sponsor ad messages and introduce world-class performers who do a few songs each, prioritising old chestnuts that they know fans want to hear. Any given night, the lineup may include mainstream country stars of the present and the distant past, bluegrass bands, gospel vocal groups, singer-songwriters, hotshot instrumentalists, down-home comedians, square dancers and more. Lineups often span several generations and are often described as one big family: back in March, the Opry’s most veteran member, 87-year-old Bill Anderson, appeared the same night that Stuart and his band the Fabulous Superlatives backed his bassist’s rockabilly obsessed, 10-year-old son.

The Opry has absorbed a century’s worth of technological, musical and cultural evolution at a very measured pace. Its leadership has apologised for employing blackface duos in its early days; its traditional barn backdrop is now comprised of video walls and its stage has welcomed artists bringing hip-hop, gen-Z folk and TikTok virality to the genre. “You have to evolve,” says Rogers. “It’s a must for survival and for creating really interesting shows – but you do it in a way that’s really respectful of this institution.” Today, membership of the Opry, awarded to a small cadre of musicians – just 76 living artists – has become one of the industry’s greatest honours.

The Opry was originally almost incidental programming on a radio station, WSM, launched in 1925 by National Life and Accident, a Nashville insurance company looking to promote its business. Station managers filled the airwaves with a hodgepodge of locally available acts, professional or not, and people soon began showing up to watch the broadcast. “It was a matter of: let’s see who we can get to come in here,” says historian Brenda Colladay, a longtime curator of the Opry’s collections who has helped to research a thorough 100th anniversary book.

There was no such genre as country music when the show launched, just regionally specific versions of old-time music, dance tunes and folk songs. Over time, the sheer variety of performers featured in Opry lineups helped forge a cohesive identity out of those disparate styles, fundamentally shaping how we understand country.

Alongside light classical fare were acts such as Uncle Dave Macon, a banjo-playing vaudevillian, and DeFord Bailey, a young Black harmonica wizard whose family string band had long played area dances. The Opry was essentially a barn dance on the radio, an already popular concept – they poached their master of ceremonies George D Hay from a rival show in Chicago.

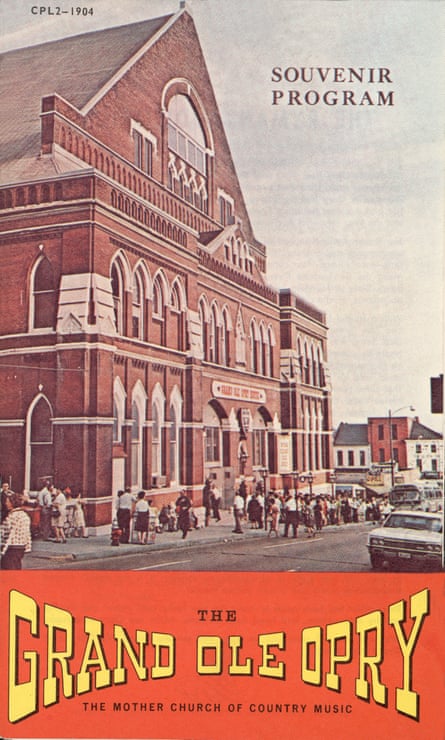

But the Opry initially faced local opposition from upper-class residents who fancied Nashville “the Athens of the South”, complete with a replica of the Parthenon, then under construction. “It made some people ashamed that [Nashville was] associated with hillbilly music,” Colladay says, including Tennessee governor Prentice Cooper who declined an invitation to attend an Opry celebration: “He felt like it was really hurting Nashville’s reputation.” Cooper was vastly outnumbered by the listeners who heard themselves in the show. As it went nationwide, it developed a massive, devoted following among rural and small-town listeners, as well as southerners who had migrated to industrialised cities. It got so popular that National Life and Accident executives got annoyed with rowdy fans clamouring to watch the live broadcasts at the company offices, and the Opry eventually moved to Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium in 1943.

By then, it was no longer free to get in, and WSM had established an in-house booking agency that sent performers on the road. Staff and stars saw opportunities to capitalise on the show’s dominance in other ways, starting a recording studio, music publishing houses and enough other businesses to entice New York-based record labels to set up local operations. The presence of the Opry ensured that Nashville became home to the emerging, professionalised country music industry.

It was where the thrillingly hard-driving new style of bluegrass was fleshed out, and where honky-tonk singers and folk-friendly troubadours alike found a home, but the show was sometimes too cautious to embrace trends. Take Elvis Presley: when he wasn’t invited back after his first Opry appearance, he moved on to a rival show in Louisiana. Stuart says the Opry might occasionally overcorrect, and points to its early-80s focus on the slick “urban cowboy” movement: “From time to time, I would tune in to the Opry, and when they introduced somebody, I kind of knew what song they were about to sing and what joke they were going to tell. It was a little weary.”

Splashy additions like the Opryland theme park and regularly televised broadcasts on the Nashville Network brought in new listeners, as did the 2010s TV drama Nashville, set in the city’s country songwriting scene. But because the Opry was home to many generations of performers at once, there were times when some of the dedicated members felt they were denied opportunities to appear – Stonewall Jackson brought an age discrimination lawsuit, which was settled with undisclosed terms. And of more than 230 acts granted membership over the years only two Black country stars, the late Charley Pride and Darius Rucker, have been inducted since Bailey – and Bailey was fired during a copyright-related dispute in 1941, an injustice the Opry recently apologised for.

But Rogers reports that for the last few years a double digit percentage of Opry’s performers have been artists of colour, making it much more diverse than contemporary country radio; according to leading researcher Dr Jada Watson, radio devoted less than 3% of its spins to artists of colour in 2024, despite Beyoncé’s Cowboy Carter coming out that year. Rogers’ team began tracking performer demographics internally a few years back, “because it is right for this community and right for this show”.

Equal Access, a DEI programme that helps businesspeople and music-makers of underrepresented identities navigate the country music industry, has forged a friendly relationship with the Opry. Programme manager Chantrel Reynolds says she and her colleagues made sure it was a safe space for discussing the Opry’s complex history with race before they began arranging visits with Opry leadership, and she finds that acknowledgment refreshingly “different from a lot of spaces” in country music. The Opry, she says, is “actively trying to programme these things, not just in Black History Month, but all year round”.

With the help of Equal Access, contemporary country artist Angie K got her first chance to play the Opry last year. “I was the first person from El Salvador to play that stage,” she says. “I needed to be not just good – I have to be great, so great that they think, ‘We need to do this again with another Latin artist.’” She had scoured Opry history for predecessors who are queer and Hispanic like she is. “I’m very aware that there’s not many. What I love about the Opry is there’s still room to grow – they’re making a very intentional effort to change.”

On the show, she sang originals addressing women as romantic interests, and she was “very grateful that a lot of people came up and said, ‘I’m so happy that you said those pronouns.’” For his part, Stuart marvels at how the Opry always finds its way back to varied vitality after weathering all manner of growing pains: “The thing that the history books tell me is that every institution goes through that from time to time”.

The Opry expects decorum: there’s no alcohol backstage, just tea and lemonade, and in keeping with Federal Communications Commission rules, no cursing on stage. But Rogers sometimes dispenses reassurance to first-time performers who assume they should be at their most traditionalist. “That crowd out there is really full of all kinds of people, all walks of life,” he tells them. “Bring what you do to this stage. We wouldn’t have invited you to be on this stage if we weren’t up for what you bring.”

3 months ago

134

3 months ago

134