Wig, robes and moves like Jagger. Rosamund Pike’s star turn as a crown court judge, at the National Theatre in London, has proved that there’s just one prop you need to turn even the most serious of subjects into a punk performance – a microphone. And Inter Alia is only the latest in a number of major openings to star the humble handheld: from Greek tragedy to Chekhov, the device seems to be increasingly common in West End productions.

Microphones were integral to Thomas Ostermeier’s meta-theatrical production of The Seagull at the Barbican, and Jamie Lloyd – having used handhelds to transform James McAvoy into a rapping Cyrano de Bergerac three years ago – has deployed them in both Shakespeare (Much Ado) and Lloyd Webber (Evita). And no production used them more controversially than Daniel Fish’s Elektra, whose lead, Brie Larson, spoke her entire part into an on-stage amp, distorting her own voice with a range of effects pedals.

Microphones have been a source of contention in the theatre ever since Trevor Nunn introduced radio mics to the National in 1999. But a handheld isn’t something a director is trying to hide, unlike the miniature, hands-free microphones that audiences are now used to seeing actors wear. “Personally I think those things that sit on the top of people’s foreheads, like a bug, look silly,” says Fish. “But here the microphone becomes an instrument, right? It’s something that the actor can play with so it becomes a very dynamic thing.”

While it might not have been in use in Sophocles’ time, Fish found it a fascinating proposition in the rehearsal room. “Elektra is about a woman who refuses to be quiet, so the idea of amplifying and centring her voice felt important,” he says. “This is a person for whom the only power that she has, the only chance of justice, is through the noise she makes.”

One of the memorable elements of Larson’s sonic performance was the way she sang, rather than spoke, the word “no” – highlighting just how many times it appears in the play, although the punk sensibility did divide the critics. Or, as Fish puts it, “the show pissed a lot of people off”.

Ostermeier enjoys the “attitude” that handheld mics can bring to a performance (put one in a rehearsal room, and every actor wants to be the one holding it). “Of course, it’s about who has the power to talk and who is excluded, about status and power,” says the German director, “but it’s also about pop culture.” Ostermeier enjoys placing theatre within the context of the entertainment industry it belongs to: his Seagull kicked off with an actor performing some Billy Bragg, then asking the audience if they were ready for “a little bit of Chekhov”.

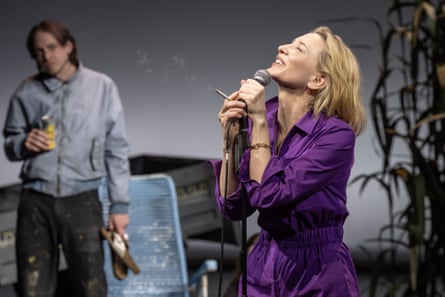

In that deliberately meta production, on-stage microphones were employed throughout to help indicate when characters were speaking to each other or “performing” for a wider audience. Cate Blanchett found it transformative for the part of Irina Arkadina, a famous actor and hopeless showoff: “They helped the story we wanted to tell,” says Ostermeier, “which is that Arkadina is completely lost in it. She doesn’t have a real relationship with other human beings any more without some form of media in between.”

There is nothing new about handheld mics on stage, as all these directors are keen to point out: pioneers from the Wooster Group to Pina Bausch to Marina Abramović were using them in the 1970s. “It’s a technique that’s been around for a long time,” says Katie Mitchell, whose wordless, sonically driven work Cow | Deer arrives at the Royal Court in September. “I’ve always been interested in how you can amplify the spoken voice without having to distort your body or your voice to make it sound louder,” says Mitchell, who has been working with microphones for decades now (in her own version of The Seagull in 2006, Hattie Morahan’s Nina whispered her lines into one).

It’s a paradox of the microphone that while it presents as performative and even political, it can also bring us closer to the character’s subjective experience. “We’re being invited into a more intimate relationship – we can hear their saliva, their breathing,” says Mitchell. That requires technicians as sensitive and responsive as the performers themselves, such as Laura Hammond, the sound engineer who live-mixed the scenes in Elektra. “A lot of times everything just goes into the computer, everything is set,” says Fish, “and that makes me want to pull my hair out.”

For some theatre lovers, the current vogue for on-stage amplification is less welcome. One veteran actor in Ostermeier’s own company, who like so many stage actors has trained his voice to fill large spaces, refuses to use microphones. “He’s annoyed because it’s a theatrical fashion,” says the director, “and he doesn’t want to be part of this fashion any more.”

Mitchell acknowledges the challenge microphones represent to the proud tradition of voice work in theatre: “There’s a sense if you’re not allowing actors to use all their skill for vocal projection and you’re just mediating it with technology, this undermines that tradition. But I’m always of the position that a healthy society should have a wide spectrum of performance modes.”

As ever, there’s a danger that a popular technique becomes a fad, used without a sense or purpose. “It moves from innovation to convention to cliche awfully quickly,” admits Fish. But right now, Mitchell believes the age of the microphone is something to be enjoyed. “All these practitioners have got good political or intellectual underpinnings – let’s celebrate it, and not police each other. Let’s just chill.”

3 months ago

116

3 months ago

116