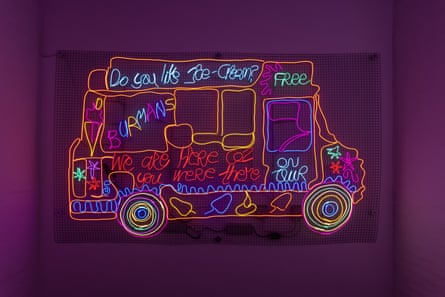

It is November 1985 and in a corridor of London’s ICA, a pivotal moment in British art history is about to take place. Curated by Lubaina Himid, The Thin Black Line displays work by 11 Black and Asian women artists, hung on the walls of the museum’s narrow walkway – to signify just how they’ve been marginalised. Their work – which explores social, cultural, political, feminist and aesthetic issues – comes as a shock to the stuffy art establishment.

Critics dismiss it, or deride the works as “angry”. And yet this show, placing Black women artists firmly at the centre of contemporary British art history, will come to be seen as a turning point, paving the way for future winners of the Turner prize (Himid and Veronica Ryan) and Venice Golden Lion (Sonia Boyce).

Forty years on, the ICA is revisiting the show with Connecting Thin Black Lines 1985–2025, building on its legacy with new and old works from the original artists, and new contributors. Here, some of them reflect on the original exhibition, the reaction it received, and how the art world has changed.

Sutapa Biswas: The 1980s were a charged time politically, socially and economically. I arrived at art college in 1981 with a great degree of understanding about the histories of the empire and how it impacted my parents. They were born in what was called British India. They experienced partition and genocide and were displaced. It was a complex time in the UK, too. In my community in west London, the Southall Youth Movement, an antiracist group, had burned down the Hambrough Tavern where skinhead bands played.

Marlene Smith: I was a student, studying for my BA at Bradford School of Art. By the time I joined the BLK Art Group, an association of young Black artists, I was already thinking about my identity in relation to feminism. I was not the only Black person studying, but I was one of few. I was certainly the only person trying to make work with political overtones.

Jennifer Comrie: I was living through a really interesting time: the Troubles, the miners’ strike, Thatcherism, apartheid in South Africa. My work reflected this. Art for me has always been a wayto garner a better understanding of myself and the world around me.

Ingrid Pollard: I was doing various jobs, and signing on for benefits. I was a cleaner. I was a gardener for the council. There weren’t any rosy aspirations to be an artist. I had been doing screen-printing in an evening class and then a job came up in this feminist print shop in London, which I got, much to my surprise. There was a dark room there, so I started doing photography.

Sutapa: One day on my university course, I was confronted by a painting by Turner titled The Slave Ship. My tutor was talking about the expressionistic nature of the brushmarks. I was sitting there thinking: “What about what’s in the water?” That moment, coupled with what I heard in another lecture, made me think: “We’re talking about class and gender – but we’re not talking about race.”

Marlene: My painting tutor didn’t like what I was doing. He was not at all convinced that art could, or should, be political. So when Lubaina showed up and stood in front of my work and had a conversation with me, it was totally transformative.

Jennifer: When Lubaina came in to my studio by chance and looked at my work, she was intrigued and asked if I would be interested in showing it. Initially I was unsure. I did not realise how pivotal this chance meeting would be.

Sutapa: I found out Lubaina was doing a talk and went along. I introduced myself and said: “I’m a student at the University of Leeds. I’d love to interview you.” When I submitted my dissertation, I invited Lubaina to do a talk at the university. There, she saw my painting Housewives with Steak-Knives and the video work Kali. “I’m organising this exhibition,” she said. “I would love to include your work.”

Marlene: The show was coming up, but I had no idea what to make. Then Cherry Groce was shot [during a police raid on her Brixton home]. So I made Good Housekeeping – a larger than life painting of a woman leaning against a doorway. Behind her outstretched arm is a framed photograph of my sister’s birthday party. Above that image, painted on the wall, are the words: “My mother opens the door at 7am. She is not bulletproof.” I was thinking about Cherry Groce as a middle-aged single mum.

Sutapa: The rhetoric was so racist in Britain. So I began to think about performance as strategic intervention. That’s what emerged in Kali. But it also has a presence in Housewives with Steak-Knives. It’s not a static piece, settled against the wall. It sits forward and looks as if it’s going to fall on top of you.

Jennifer: Coming to Terms Through Conflict, a work I put in the show, questions identity: northern, Jamaican, British, Black, Christian, etc. Untitled continued this journey. Its broken stitching is intentional, representing a refusal to be contained or defined by social constraints – church, family, anyone. It’s a visual declaration of freedom.

Marlene: Jenny had this beautiful singing voice. I remember her singing as we were installing. Even when I think of it now, it chokes me up. I remember Sutapa climbing up and writing the words for my work in black paint.

Ingrid: It was fun installing it all. We thought we were being slightly naughty, because it was a well-known gallery. It was only later that I understood the ramifications, the politics of what Lubaina was trying to organise.

Helen Cammock [involved in new show]: I was 15 when that exhibition was at the ICA. I wasn’t interested in art then. It wasn’t on my radar until 2005, when I did a photography BA. I had bought some books that contained Ingrid’s work. Postcards Home [her photography book about England and the Caribbean] was on my desk while I wrote my dissertation. The images moved me. I was sad. I was angry. I found beauty.

Marlene: The response to The Thin Black Line, in terms of art criticism, was pretty appalling. The critics came to it very defensively, rather than looking at what the work had to say. Sutapa and I wrote a piece for Spare Rib magazine, talking about the lack of useful critique around Black artists.

Sutapa: The reviews were reduced to questions of identity and that became a platform for white guilt. But the real issue was avoiding the language of our practice, in the way that you might talk about the language of David Hockney’s work or Helen Chadwick’s. We weren’t being afforded the same level criteria. They weren’t dealing with the aesthetics of our practice.

Helen: It’s not a new thing. It happens now. This notion that you’re angry. That you’re didactic. It’s a marginal experience and people aren’t interested in it. The whole framing of the show undermined the quality of its ideas, of its potential to shake people’s ways of thinking and seeing.

after newsletter promotion

Marlene: You would expect a show like The Thin Black Line to create opportunities, but the opposite happened. If you examine the YBAs, there was a synergy with what had happened earlier with the Black Arts Movement; it’s striking that they seemed to be using our methods of DIY. However, they were not including the Black artists in their projects.

Ingrid: There was never a time, after, when I wasn’t making art. I wasn’t ill. I didn’t have children. I was teaching as a way of keeping a regular income. I didn’t have to deal with the aspirations of a gallery representing me. Those things were very alien.

Marlene: In 2011, Tate did a show looking back at The Thin Black Line. And then Graves Gallery stumbled across work by the BLK Art Group and did a show. So that felt like something was happening. Over the last 10 years, it feels like there’s been a resurgence of interest in the Black Arts Movement because, despite its significance, it has not made it into discussions of art history.

Amber Akaunu [involved in new show]: I studied art and art history at Liverpool Hope University from 2015 to 2018. I didn’t really learn about Black art history. I feel a bit of pain when I find out about things I didn’t know. I started a magazine with another artist in the course called Rooted. We just felt there was a big gap in knowledge.

Sutapa: After the show, I continued to work. I showed with Vito Acconci, Tania Bruguera, Doris Salcedo and Louise Bourgeois at Iniva in London. In 2004 I had a show there that was not nominated for the Turner. Where is my retrospective at the Tate? Where is Claudette Johnson’s? I have not received accolades for my recent exhibitions at the Baltic and Kettle’s Yard.

Ingrid: Getting recognition came after a long period of work, 20 to 30 years. I was surprised to be nominated for the Turner. It raises your public profile. The media had ignored me and a lot of artists for 40 years.

Marlene: I had a solo show called Ah, Sugar in2024. At the opening, Lubaina introduced me to the curators from the ICA and said that this new exhibition, Connecting Thin Black Lines, would be coming up. It was a surprise, exciting.

Helen: I was looking at the complete lineup. Their voices weren’t heard before – and now they are being heard more loudly than ever.

Amber: Lubaina hosted a lunch for some of the artists who were going to be in this new show. I just sat there and soaked everything in. It was shocking – but touching – to hear their stories. A lot of these artists have gained so much success, but you can still hear the hurt. I related so much. Some 30 to 40 years on, I’m having similar experiences. I remember curating an exhibition over four days, and showing some work for Black History Month, and we weren’t paid for it.

Ingrid: A lot of the young students I speak to are still complaining: lack of recognition, opportunities. Things change, but they remain the same. My advice is you need a gang. You can’t do it on your own. It takes a village to make an artist.

Helen: It happened to be a really monumental experience for me being in a show called Carte de Visite with Claudette Johnson and Ingrid Pollard in 2015. I think it encapsulated what’s happening now, the interconnectedness across generations.

Marlene: It was a real privilege for me to exhibit with them in the first place. And it’s a real privilege to be reunited. It’s always nerve-wracking when you make new work. There’s a bit of an echo between the piece I’ve made this time and the 1985 piece. This piece is probably more gentle. Amber: The film I’m showing is about motherhood and friendship. It’s a documentary style that that explores my childhood being raised by a single mum in Toxteth, Liverpool.

Jennifer: It’s incredible to see the works being recognised again after 40 years. It genuinely feels like a few moments ago we were setting up the works in the ICA’s corridor.

Ingrid: I’m hoping the exhibition annoys a lot of people in the art world. When they had an opportunity to engage with these artists, they didn’t take it. So it’s like: “See what you missed out on, mate.”

2 months ago

93

2 months ago

93