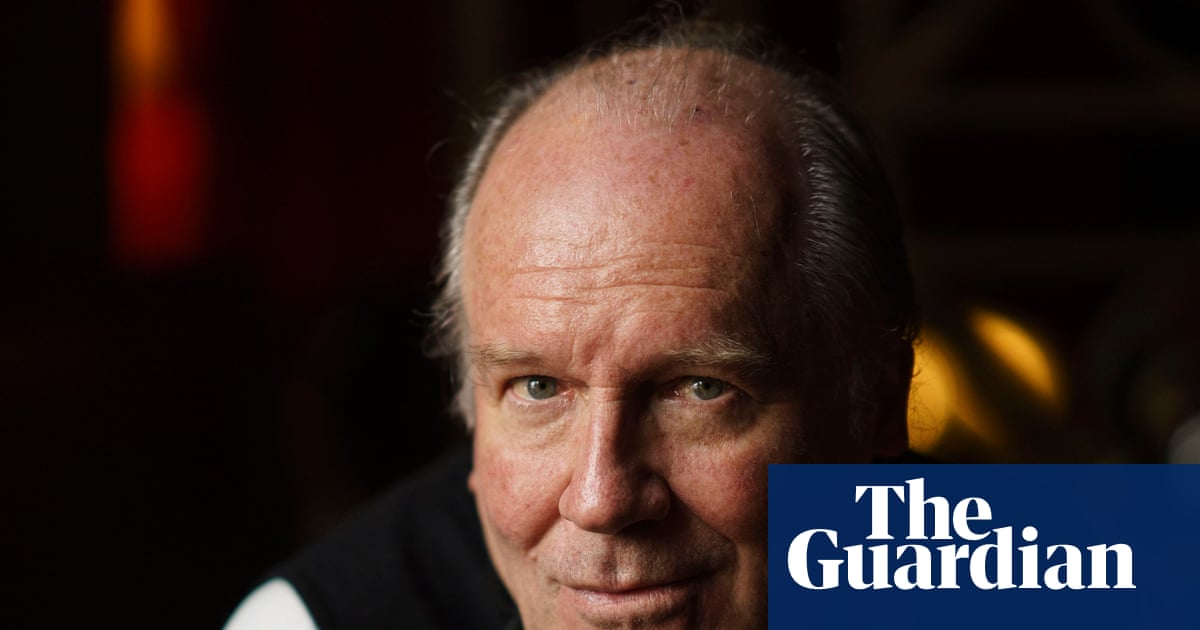

Pippa York used to be Robert Millar, a stage winner and king of the mountains in the Tour de France and Giro d’Italia. Millar was also a podium finisher, in both the Vuelta a España and the Giro, a British national champion, and Tour of Britain winner. But Millar had also wanted to be a girl since the age of five, a secret that remained buried throughout childhood in Glasgow, the subsequent racing career, and beyond, into mid-life.

In her new book, The Escape, written in collaboration with David Walsh, the 66-year-old unflinchingly documents the long and painful process towards transition and the isolation, fear and loneliness that went with it.

“There was no LGBTQ community in the Gorbals where I grew up,” she says. “If I saw David Bowie on Top of the Pops, I thought: ‘Oh, that’s interesting,’ but he wasn’t a role model. It didn’t make me think I could be whatever I wanted.”

The book – part Tour de France travelogue, part memoir – is about “escaping working in a factory, escaping the real world, and escaping being born male”. Cycling offered that escape and York went from “messing about on bikes” to serious road cycling in mid-teens. “I liked the freedom, the speed, the danger, the going fast.”

She says that she had felt “different” from the age of five and with that feeling came shame and isolation. “You realise the others are going to beat you up. Then there’s the fear of being outed and the shame of not fully fitting into the group that you’re meant to be part of. Now, they have Pride marches, but I felt very little pride.”

This was the early 1970s. She says that if she could have stalled her physical development, she would have been “that young person, with no qualms, none at all.”

“If you look at puberty blockers, that’s going to start around 12. Young girls are given the pill, so are we going to say that’s not OK? The decisions being made now over puberty blockers are purely political.”

The British government’s Commission on Human Medicines (CHM) has advised that there is currently a safety risk in the continued prescription of puberty blockers to children. It recommends indefinite restrictions while work is done to ensure the safety of children and young people.

York seems uncertain if her family were aware of her body dysphoria. “I don’t know. It was the 1970s. I can’t ask my father because he’s not here. Even now, you don’t want your kid to be different, because you know there’ll be a stigma attached.”

Sitting calmly in the anonymity of a west London business hotel, she recalls the alienation and loneliness of her time in the European peloton, from 1980 to 1995. When she turned professional, was the cycling pack, however brutal, a safe haven?

“I learned to fit in. It wasn’t always welcoming, but it wasn’t hostile all of the time. I didn’t ever feel bullied. Abused by the system, the workload and the management, yes – but not bullied. Racing takes all of your concentration. If you’re in the race, you’re not processing the outside world. You have no time to dwell on any other stuff.”

Robert was still different enough to be picked on though. “People would throw out homophobic slurs, that kind of verbal intimidation, but it just washed over me. I learned to deal with it. I gave it back. I could swear in most languages.”

She says that, as Robert the bike racer, she kept an “emotions box”. “I didn’t need emotions. They were just going to get in the way. I learned to do that quite well. The shield I put around me allowed me to function.”

But that also fuelled a deepening depression that settled on her in the mid-1990s. “It got worse when I stopped racing. I thought: ‘Who am I?’ The bike rider was gone. I had to deal with that. But I was also dealing with: ‘Am I going to transition or not?’”

It took her five years to seek out professional help. “I was in a bad place, really, really depressed. I had no idea if I would fully transition or not. But I had to find out where on the transition journey I would end up. I never felt suicidal, but I understood why people did.

“You think: ‘I might be OK with a little bit of therapy, with counselling, or hormone replacement.’ But you don’t know where you’re going to stop. I just about got through the millennium, but it wasn’t sustainable. I wasn’t functioning and I couldn’t continue as I was.”

After major surgeries followed by long recoveries, there were further challenges. “It became: ‘What kind of woman am I going to be?’ It was stuff I had to learn. I learned that as an adult, all the small social clues. I had to learn them very quickly so I didn’t appear vulnerable.”

York is now a respected voice in the cycling media and also an advocate for trans athletes. “It’s more understood now,” she says, “but I don’t think it’s more accepted.”

She states that the idea that “somebody who’s been through male puberty has this innate advantage is just ludicrous. People come in all sizes. Each of us has different levels of testosterone at which our body is healthy.”

after newsletter promotion

Asked how she would feel if, competing as a woman, she was beaten by a trans athlete, York says: “I would wonder if they did have an advantage, but I would look at their performances. ‘Are they better than me because they were born male, or are they better because they’re more talented? Or have more time to train, or better equipment?’

“People don’t understand the physiological changes. Your testosterone basically drops to zero. Testosterone doesn’t make you stronger, it’s part of the system which repairs the damage done by exercise.”

However this is not the position taken by UK Sport, Sport England and the other major sports councils in Britain. After conducting a review of the scientific literature it said that trans women retain physique, stamina and strength advantages when competing in female sport, even when they reduce their testosterone levels. As a result, it has told sports that there is no magic solution which balances the inclusion of trans women in female sport while guaranteeing competitive fairness and safety.

York was invited initially to be part of British Cycling’s advisory group on diversity and inclusion but the controversy over the trans athlete Emily Bridges soon ended her relationship with the national federation.

“There was a potential for Emily to be part of the track team but suddenly it all stopped,” says York. “She was high performing, but it wasn’t domination. She was 10 or 12 seconds off the world record, but it might have been enough to get on the squad.”

She avoids labelling British Cycling as transphobic, but believes that the federation has a “real problem with the whole LGBTQ+ spectrum. They say they don’t, but they do.” She went on to claim that: “They have had people, employees, who have signed a letter to the UCI, demanding that trans women be excluded … In any other organisation, those people would be fired.”

In response, a British Cycling spokesperson said: “We strongly believe that cycling is for everyone and are committed to welcoming as many people as possible into our sport.

“Our competition policies – in line with most other sports - intend to safeguard the fairness of competitive cycling … Anyone can compete in our ‘Open’ category, including transgender women, transgender men and non-binary individuals.

“British Cycling takes allegations of homophobic and transphobic behaviour extremely seriously and has a zero-tolerance approach. We are proactively working to ensure that cycling is as accessible and welcoming as possible.”

During the 2023 world championships in her home city, the official programme and BBC coverage deadnamed York. “I was Scotland’s best road cyclist in history, but I didn’t exist,” York said. “How can you justify not having the correct name and my identity now?”

She is hopeful, though, if not optimistic, that by the time 2027 comes around, her legacy to British cycling will be properly acknowledged. “If you are going to mention my previous existence you’re going to have to mention who I am now,” she said. “I haven’t disappeared, and I haven’t died. I am not a refugee from who I was before.”

The Escape by David Walsh & Pippa York (HarperCollins Publishers, £22). To support the Guardian, order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.

In the UK and Ireland, Samaritans can be contacted on freephone 116 123, or email [email protected] or [email protected]. In the US, you can call or text the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline on 988, chat on 988lifeline.org, or text HOME to 741741 to connect with a crisis counselor. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is 13 11 14. Other international helplines can be found at befrienders.org

3 months ago

152

3 months ago

152