In 28 Years Later, zombies maraud over a Britain broken by more than Brexit. Its director discusses cultural baggage, catastrophising – and why his kids’ generation is an ‘upgrade’

The UK is a wasteland in Danny Boyle’s new film. Towns lie in ruins, trains rot on the rails and the EU has severed all ties with the place. Some residents are stuck in the past and congregate under the tattered flag of St George. The others flail shirtless through the open countryside, raging about nothing, occasionally stopping to eat worms. You wouldn’t want to live in the land that Boyle and the writer Alex Garland show us. Teasingly, on some level, the film suggests that we do.

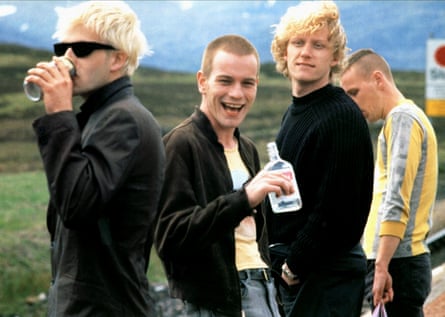

Boyle and Garland first prowled zombie Britain with their 2002 hit 28 Days Later. It was an electrifying piece of speculative fiction, a guerilla-style thriller about an unimaginable world. Since then we’ve had Brexit and Covid, and the looming threat of martial law in the US … The story’s extravagant flights of fancy don’t feel so far-fetched any more. “Yes, of course real world events were a big influence this time around,” Boyle says, sipping tea in the calm of a central London hotel. “Brexit is a transparency that passes over this film, without a doubt. But the big resonance of the original film was the way it showed how British cities could suddenly empty out overnight. And after Covid, those scenes now feel like a proving ground.” Where Cillian Murphy first walked, the rest of us would soon follow.

Tense and gory, 28 Years Later is a fabulous horror epic. I would hesitate to call it a sequel, exactly: it’s more a reboot or a renovation; a fresh build over an existing property. Newcomer Alfie Williams plays 12-year-old Spike, who defies his parents (Jodie Comer and Aaron Taylor-Johnson) and flees the sanctuary of Holy Island for an adventure on the infected mainland. Along the way, he tangles with berserker zombies and smirking psycho-killers, and encounters Ralph Fiennes’s enigmatic, orange-skinned Dr Kelson, reputedly a former GP from Whitley Bay. All of which makes for a jolting, engrossing journey; a film that freewheels through a gone-to-seed northern England before crashing headlong into the closing credits with many of its key questions still unanswered.

The hanging ending is the point, Boyle explains, because the film is actually the first part of a proposed trilogy. Sony Pictures has put up two-thirds of the budget. The second movie – The Bone Temple, directed by the American film-maker Nia DaCosta – is already in the can. Boyle has plans to shoot the final instalment, except that the future is unwritten and the industry is on a knife edge

“Sony has taken a massive risk,” the director tells me happily. “The original film worked well in America to everyone’s surprise, but there’s no guarantee that this one will. It’s all because of this guy, [Sony Pictures’ CEO] Tom Rothman. He’s a bit of a handful, a fantastic guy, runs the studio in a crazy way. He’s paid for two films, but he hasn’t paid for the third one yet and so his neck’s on the line. If this film doesn’t work, he’s now got a second film that he has to release. But after that, yeah, we might not get to complete the story.”

Good directors reflect the times they work in, but they’re at the mercy of them, too, hot-wired to the twists and turns of history; up one year and down the next. And so it is with Boyle, who’s travelled from the sunny Cool Britannia uplands of Shallow Grave and Trainspotting through the imperial age of Slumdog Millionaire and the London Olympics, right down to the shonky doldrums of today, when a cherished project might collapse under him like an exhausted horse. He’s 68 now, and battling to get his films across the line. I don’t know why he’s so cheerful. Hasn’t everything gone to hell?

“Well, I’m an optimist,” he says. “So I don’t despair about things the way I know that a lot of people do. Also I’m slightly more outside the media than you. That allows me a slightly different view on things. And increasingly, as I age, I become more wary of the obsessions of the media. That constant catastrophising and sense of perceived decline.”

It’s particularly noticeable in the US, he thinks. “Much of Trump’s dominance is undoubtedly down to his appeal to the media. He is so media friendly. His soundbites, everything about him, fit hand in glove with news and entertainment to the point where it’s damaging. Whereas in this country, we’re quite fortunate. We’ve dodged the far-right bullet for the moment and we elected Keir Starmer against the tide of what’s been happening elsewhere.” He reaches for his tea. “It could be a lot worse.”

In 2012, Boyle devised and directed Isles of Wonder, the opening ceremony of the London Olympics. The show was a triumph: a bumper celebration of British culture that made room for James Bond and the queen, Windrush migrants and the NHS, Shakespeare and the Sex Pistols. “But my biggest regret was that we didn’t feature the BBC more. I was stopped from doing it because it was the host broadcaster. Every other objection, I told them to go fuck themselves. But that one I accepted and I regret that now, especially given the way that technology is moving. The idea that we have a broadcaster that is part of our national identity but is also trusted around the world and that can’t be bought, can’t be subsumed into Meta or whatever, feels really precious. So yeah, if I was doing it again I’d big up the BBC big time.” He laughs. “Everything else I’d do exactly the same.”

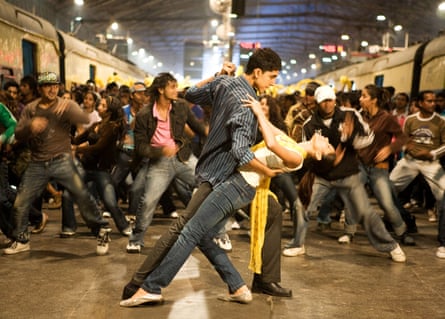

Isles of Wonder has safely passed into legend. These days it’s up there with James Bond and the queen. I wonder, though, how history will judge Slumdog Millionaire, his Oscar-winning 2008 spectacular about a ghetto kid who hits the jackpot. Boyle shot the film in Mumbai, partly in Hindi, and with a local crew. But it was a film of its time and the world has moved on.

“Yeah, we wouldn’t be able to make that now,” he says. “And that’s how it should be. It’s time to reflect on all that. We have to look at the cultural baggage we carry and the mark that we’ve left on the world.”

Is he saying that the production itself amounted to a form of colonialism? “No, no,” he says. “Well, only in the sense that everything is. At the time it felt radical. We made the decision that only a handful of us would go to Mumbai. We’d work with a big Indian crew and try to make a film within the culture. But you’re still an outsider. It’s still a flawed method. That kind of cultural appropriation might be sanctioned at certain times. But at other times it cannot be. I mean, I’m proud of the film, but you wouldn’t even contemplate doing something like that today. It wouldn’t even get financed. Even if I was involved, I’d be looking for a young Indian film-maker to shoot it.”

A waiter sidles in with a second cup of tea. Boyle, though, is still mulling the parlous state of the world. He knows that times are tough and that people are hurting. Nonetheless, he insists that there are reasons to be cheerful.

“Have you got any kids?” he asks suddenly. Boyle has three: technically they’re all adults now. “And I think that’s progress. I look at the younger generation and they’re an improvement. They’re an upgrade.”

The director was weaned on a diet of new wave music and arthouse cinema, Ziggy Stardust and Play for Today. He began his career as a chippy outsider and winces at the notion that he’s now an establishment fixture. “It all comes back to punk, really,” he says. “The last time Lou Reed spoke in public, he said: ‘I want to blow it all up,’ because he was still a punk at heart. And if you can embrace that spirit, it keeps you in a fluid, changeable state that’s more important than having some fixed place where you belong. So, I do try to carry those values and keep that kind of faith.” He gulps and backtracks, suddenly embarrassed at his own presumption. “Not that my work is truly revolutionary or radical,” he adds. “I mean, I’m not smashing things to pieces. I value the popular audience. I believe in popular entertainment. I want to push the boat out, but take the popular audience with me.”

I suggest that this might be a contradiction. “Yeah, of course it is,” Boyle says, snorting. “But I’ve found a way to resolve it – in my own mind, at least.”

If 12-year-old Spike played it safe he’d have stayed on Holy Island beside the reassuring flag of St George. Instead, the kid takes a gamble and charts his own course to the mainland. He’s educating himself and embracing a fraught, messy future. He’s mixing with monsters and slowly coming into his strength. That’s what kids tend to do, Boyle explains. That’s why they give us hope. “Maybe hope is a weird thing to ask for in a horror movie,” he says. “But we all need something to cling to, whether that’s in films or in life.”

3 months ago

89

3 months ago

89