Richard Beard, award-winning author of The Day That Went Missing and Sad Little Men, thought he was writing his next book, a whole life memoir. In the event, he has written his way off the page and into an entirely new publishing model. The Universal Turing Machine is the title both of Beard’s memoir and the mass memoir project he hopes others will help him to build.

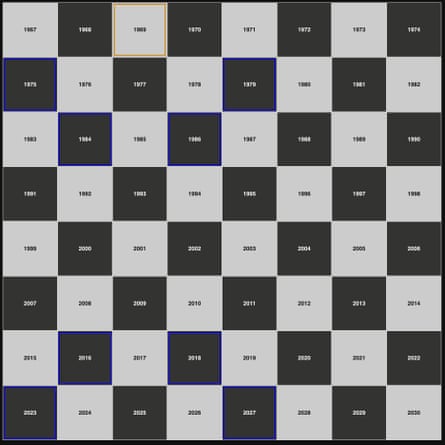

Organised as a chessboard, each of the 64 squares narrates one year of Beard’s life, in 1,000 words per year. (He’s 58, so the last five years are fictionalised.) The reader moves around the “board” as if they were a knight, picking the next year to read from options limited by the knight’s L-shaped ambulation.

“The way you go round it, what you want to know, will tell you something about yourself,” he says. Each entry or square contains signposts to future and past entries; you can pick your subplot or skip to the juiciest bits, read faithfully or game the machine. The public are free to respond to the constraints of the board however they choose, merging or repeating years, provided they submit 64 years to fit the shape of the board, each of no more than 1,000 words. The memoirs will be displayed in a grid with each square a clickable whole-life memoir. As more are published, the overall grid of the “machine” will grow.

The project takes its title from the test that Alan Turing devised to discern artificial intelligence from human intelligence. “The idea is that if you write your memoir, you are passing the Turing test,” Beard says. “You are showing that you’re human through the life that you’ve lived, through the memories that you have. In a way, it’s a resistance to AI-generated content.”

Beard’s memoir is beautifully written, with a dedication to emotional accuracy that feels both tender and ruthless. “Much of the kindness in our marriage involved leaving the other person alone,” he writes, “which often went unnoticed.” Or of his dad’s last breaths: “We fed him drops of water from the spout of a rainbow-striped teapot and watched the mist in his eyes become dominant, a grey colour like old washing-up water or wet kitchen-towel or cold lamb-fat or the outside of a blown lightbulb …”

It is impossible to resist the thought that it ought to be a book. But Beard found that however he ordered his honest memories, the process of ordering made them feel less honest. He realised he remembered specific events in his life in the context of what happened before and after them, and there was no satisfying way to represent this truth in fiction. “The thing to get your head around is that [this memoir] doesn’t work in any one order, but it does work in every possible order.

“I remembered by jumping around,” he says. The answer was to find a way for readers to jump around, too.

There are precedents for nonlinear narratives, such as BS Johnson’s The Unfortunates, which was published as loose leaves in a box, or Julio Cortázar’s Hopscotch, which contained instructions for alternative reading sequences.

“But it’s still there on the page,” Beard says. “By using technology, you can make it an immersive, interactive experience.”

Beard started out writing experimental fiction – his early works were Oulipian. Damascus (1998), for instance, used only nouns from the Times on the day the Maastricht Treaty took effect. He switched to memoir with 2017’s The Day That Went Missing, which told the story of his brother’s death by drowning; Beard was in the sea with him, aged 11. The book disclosed, and bore, its emotional constraints. Each memoir has been more revelatory than the last.

“Yes, because each time I get better at telling the truth,” he says. “I can now see that the novels were acts of deflection and evasion … I was using them to get validation, basically. Of course, I didn’t realise that at the time … Whereas once I got into nonfiction, I was just concentrating on trying to write what was true, and I’ve got much closer to what I think writing is for, and why writing is valuable.”

The Universal Turing Machine is free to read, and publication on the platform is free too. Memoirs are submitted as word documents, and will be copy edited. Beard, who used to direct the National Academy of Writing, will personally read and copy edit the first 15 memoirs to be published.

There is no commercial outcome – unless a publisher comes forward with an innovative suggestion of how to represent The Universal Turing Machine on paper. An origamist, perhaps?

“It’s uncommodified, which is one of the reasons why it feels important – and the fact that everyone can give it a go,” Beard says. “That seems to me a much more healthy way to approach writing than to get caught up in the competitive traps of sales and validation and essentially showing off.”

“It’s a way of taking writing seriously,” Beard says. “I’m enthused by it because I believe in literature. I believe in writing. And it feels a little bit threatened at the moment.”

-

Contributions to The Universal Turing Machine can be made at universalturingmachine.co.uk

3 months ago

66

3 months ago

66