The single biggest threat to the livelihood of authors and, by extension, to our culture, is not short attention spans. It is AI.

The UK publishing industry – worth more than £11bn, part of the £126bn that our creative industries generate for the British economy – has sat by while big tech has “swept” copyrighted material from the internet in order to train their models. Recently, the AI startup Anthropic settled a $1.5bn copyright case over this issue, but the ship has undeniably left the harbour and big tech is sailing off with the goods.

As a literary agent and CEO of one of the largest agencies in Europe, I think this is something everyone should care about – not because we fear progress, but because we want to protect it. If you take away the one thing that makes us truly human – our ability to think like humans, create stories and imagine new worlds – we will live in a diminished world.

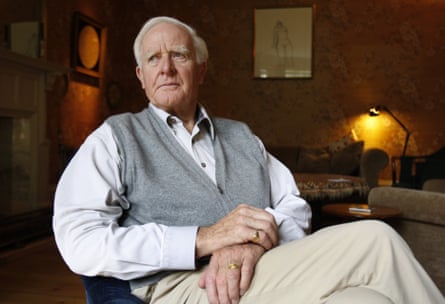

Many great writers have written about why stories are the lifeblood of humanity and how an artist’s job is to tell us truths we may not want to hear. Having worked with writers such as John le Carré, Elif Shafak, William Boyd and David Nicholls, I know first-hand where great storytelling comes from.

Le Carré was born in 1931 and survived a childhood with a conman father and a mother who abandoned him when he was five years old. He came of age as the cold war began. Treachery and betrayal was his childhood and proved – to paraphrase Graham Greene – to be the bank balance of his writing life. During his time with the secret services, it was through writing reports – and getting feedback from senior officers – that he learned to write. His skill was derived from the personal, his upbringing and his craft.

Good writing is not a regeneration of other people’s material. It is a recipe made up of having lived a life, experienced trauma and grasped one’s historical context; it is the product of artistry, craft and passion. The need to write is not something that can be encouraged – it is an illness that descends on the writer. Great writers cannot not write. They may use spellcheck and ChatGPT, but nothing would be more abhorrent to the writer than an idea being served up to them on their computer that they were then invited to “humanise”.

AI that doesn’t replace the artist, or that will work with them transparently, is not all bad. An actor who is needed for reshoots on a movie may authorise use of the footage they have to complete a picture. This will save on costs, the environmental impact and time. A writer may wish to speed up their research and enhance their work by training their own models to ask the questions that a researcher would. The translation models available may enhance the range of offering of foreign books, adding to our culture.

All of this is worth discussing. But it has to be a discussion and be transparent to the end user. Up to now, work has simply been stolen and there are insufficient guardrails on the distributors, studios, publishers. As a literary agent, I have a more prosaic reason to get involved – I don’t think it is fair for someone’s work to be taken without their permission to create an inferior competitor.

What can we do? We could start with some basic principles for all to sign up to. An artists’ rights charter for AI that protects two basic principles: permission and attribution.

For instance, no AI system should be trained on an author’s work without their explicit, informed permission. Developers should be required to publish the data sources they have used to train their systems, and be transparent so that copyright holders know when their works have been used. An artist should also be allowed to opt out (and not have to discover the option hidden beneath thousands of pages of terms and conditions).

If an artist/writer finds the technology is significantly distorting the meaning of their work, image or creation so that it is unrecognisable from the original, they should be entitled to withdraw permission of its use.

We should also introduce a label system – akin to the GM food labels – that prohibit retailers selling AI-generated stories without clear attribution. Equally, copyright must be reinforced and this can only be done at government level and even international one – a G7 of copyright.

Finally, tech companies should not be allowed to appeal to “fair use” to justify their scanning of other people’s work. This presents a real danger to the sanctity of copyright. It distorts the original intention of the “fair use” defence, which was for academics to be able to quote without fees a certain limited amount from copyrighted material.

A few simple rules such as these may not seem that important, but they may affect how your children will be educated, how our national stories are told, and how we understand who we are.

-

Jonny Geller is CEO of The Curtis Brown Group

3 months ago

97

3 months ago

97