Behind huge locked gates, the sprawling expanse of concrete and scrubland was supposed to be a hive of activity by now. Formerly the site of Barking Reach power station, these 17 hectares (42 acres) of industrial land at Dagenham Dock in east London were due to be redeveloped into a new, purpose-built wholesale food market for the capital.

However, that changed late last year when the site’s owners, the City of London Corporation, announced it had cancelled the development, which would have relocated Smithfield meat market and Billingsgate fish market.

The corporation, which is exceptionally wealthy compared with typical UK local authorities, blamed inflation and rising construction costs, despite having already spent just under £230m of the project’s £741m cost on buying and clearing the land. It has since faced a backlash over its plans to permanently close London’s ancient food markets in 2028.

“The City of London ploughed a lot into clearing the site up,” says the local Labour MP, Margaret Mullane, looking through the gates at the vacant lot.

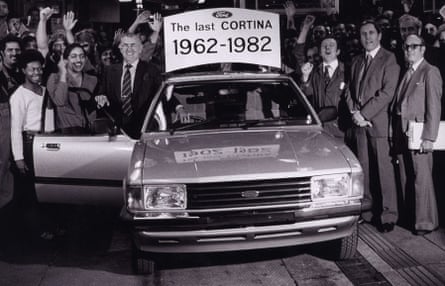

The decision was a big blow for Dagenham, located north of the Thames on London’s eastern fringe, with a proud industrial heritage once synonymous with its Ford factory, where some of the carmaker’s best known vehicles – including the Model Y and Fiesta – rolled off the production line.

The days of Ford’s dominance in the area are long gone since its 1950s heyday, when it employed about 40,000 people, compared with just under 2,000 now.

Barking and Dagenham council expected the markets would bring 2,700 new jobs to the area, boosting the local economy in the London borough which is home to 220,000 people, and also has the unhappy status of recording some of the highest levels of deprivation in the capital. The area was also ranked fifth-worst in England in the most recent index of deprivation.

A “food school” was also planned, which the corporation previously said would help create a new generation of market traders and “play a pivotal role in training future butchers, fishmongers and fruiterers, ensuring they acquire the essential skills to thrive in the industry”.

The market development, which also envisaged the relocation of the fruit and vegetable market at nearby Leyton, formed a key part of the local plan for the borough published by Barking and Dagenham council just weeks before the corporation pulled the plug.

“With the three markets not coming, and Ford, the public are quite rightly worried about unaffordable housing. What they tell politicians is it’s all about bringing good, well-paid jobs here, jobs you can raise a family on,” says Mullane, adding that many of the blocks of flats being built nearby are considered out of reach for local salary levels. “Our child poverty level is the same as Blackpool, and we have some of the lowest wages in London.”

About nine months on from the decision, it is not clear what the future holds for the Dagenham site, which is still owned by the corporation, which manages assets worth billions of pounds, and collects £1.3bn in business rates annually, most of which it passes to central government.

Dominic Twomey had not long been the Labour leader of Barking and Dagenham council when the cancellation of the markets development was announced.

While he will not criticise the financial reasoning for the decision, he concedes the planned regeneration of the site is out of his control.

“We’re in the hands of the corporation,” says Twomey. “We don’t even know whether they are planning to sell the site, or are waiting until the economy improves and are looking for other alternatives.”

Twomey and other locals also regret the lost prospects for young people in the borough.

“It’s more a regeneration loss in terms of potential opportunities, as opposed to a financial loss,” he says. “It is the opportunities it would have brought to the area both in terms of jobs and stimulating the economy there with all of the spin-offs that we might have hoped to get such as retail shops and restaurants.”

In June, the corporation announced the creation of a regeneration team tasked with overseeing the redevelopment of the current Smithfield and Billingsgate sites – due to become a cultural destination and housing – as well as finding a new location for the markets, and working with local representatives on redeveloping the Dagenham site.

The City of London Corporation says the plot is now open for other uses, adding that it is “perfectly placed to receive goods from around the world, via the Thames Estuary Gateway”.

The corporation added it would be “more specific” about the future of the site once it has engaged with property developers.

Chris Hayward, the corporation’s policy and resources chair, said: “The Barking Reach site in Dagenham Dock has the potential to be a real powerhouse for economic activity in the area, with uses that work hard for local people whilst also supporting the UK economy.”

Lack of clarity about the future of the site is just one way in which Dagenham could be now said to be treading water.

The nearby Thames freeport – which stretches eastward along the river past the Ford site to the London Gateway port in Thurrock, Essex – has recently hired consultants to draw up a master plan to “regenerate the region into a national centre for low-carbon industry, advanced logistics, and digital innovation”.

Meanwhile, Ford still owns the sprawling 450-acre plant alongside the river, where it now builds just shy of 1m diesel engines a year for vehicles such as the Transit and converts vans into specialist vehicles such as ambulances. Two ships filled with cars dock daily at its jetty on the Thames, to be transported onwards to dealerships.

However, the end of the road for diesel engines is in sight, before a planned phase-out of new petrol and diesel cars, and large parts of the plot are underused. A company spokesperson said an assessment was being carried out into the best future use of the site.

In 2016, the carmaker sold off its stamping plant – where the strikes by sewing machinists, depicted in the film Made in Dagenham, resulted in the 1970 Equal Pay Act – that has since become a large new housing development, with 4,000 homes under construction.

Despite such redevelopment of former industrial land, many residents feel let down that a long-promised railway station at Beam Park, designed to connect an area with poor transport links directly to the City of London, still has not been built, after the previous government withdrew its support.

“It’s the whole reason we moved in,” says Lewis Richardson, a resident who moved to Beam Park in late 2022. “It was supposed to be built in a year or two, and my partner was going to jump on the train to work. Now we have to rent a parking spot.”

One highlight of the council’s local plan has, however, come to fruition. A brand new film and television studio has recently opened in a somewhat unexpected location on a main road, opposite a Toby Carvery restaurant.

Reality shows, drama and commercials are now being filmed on some of the 12 sound stages at Eastbrook Studios, the largest measuring almost a third of a hectare , while the complex also offers office and workshop space.

Funded by the US investment firm Hackman Capital Partners and operated by its subsidiary MBS Group, the nine-hectare site was previously a Sanofi pharmaceutical manufacturing plant. The council acquired land with the goal of creating a “digital, science and tech cluster”, preventing it ending up as a supermarket distribution centre, says Stephen Hursthouse, MBS Group’s vice-president for studio real estate in UK and Ireland.

“Part of the site’s appeal is its size,” says Hursthouse, driving around the huge complex in a golf buggy. “From our perspective, there’s a Travelodge over the road for crew, tick; a coffee shop, tick; the tube station is right there and it’s the closest studio of its size to central London.”

While many film and TV productions tend to bring their own crews with them, Hurthouse believes there could in time be 5,000 people working at Eastbrook on multiple productions, and hopes this will inspire local young people.

“Lots of people said it wouldn’t happen, but it was bold and it has been delivered,” he says.

3 months ago

77

3 months ago

77