Hatri Echazabal Orta lives in Madrid, Spain. Maykel Fernández is in Charlotte, in the US, while Cristian Cuadra remains in Havana, Cuba – for now. All Cubans, all raised on revolutionary ideals and educated in good state-run schools, they have become disillusioned with the cherished national narrative that Cuba is a country of revolution and resistance. Facing a lack of political openness and poor economic prospects, each of them made the same decision: to leave.

They are not alone. After 68 years of partial sanctions and nearly 64 years of total economic embargo by the US, independent demographic studies suggest that Cuba is going through the world’s fastest population decline and is probably already below 8 million – a 25% drop in just four years, suggesting its population has shrunk by an average of about 820,000 people a year.

There are a number of root causes for this exodus, but most experts agree that the blockade, decades of economic crisis, crumbling public services, political repression and widespread disillusionment with the revolution have merged to become a “polycrisis”.

The unrest further undermines Cuba at a time when the Trump administration is stepping up its offensive across Latin America, heavily reinforcing US military deployment in the Caribbean, raiding Caracas to capture the Venezuelan president, and stepping up threats against the governments of Panama, Colombia and Cuba.

According to research on Cuba by Juan Carlos Albizu-Campos Espiñeira, an economist and demographer at the Christian Centre for Reflection and Dialogue in Havana, and Dimitri Fazito de Almeida Rezende at the Federal University of Minas Gerais, the Caribbean nation’s population is nowhere near the government’s 2015 projection for last year – 11.3 million – and has even fallen below forecasts for 2050.

Between 2022 and 2023 alone, researchers saw an 18% plunge in the population due to migration. The country has also recorded more deaths than births for five years running, with fertility rates stuck below population replacement levels since 1978. Now, one in four Cubans is over the age of 60, worsening economic and social prospects.

But the exodus of young people is the prime accelerator of this decline. Most of those who leave are aged between 15 and 59; 57% are women and 77% are of reproductive age. They finance their emigration through their own resources and family funds, using a worldwide network of contacts to navigate routes through Latin America, Europe, Africa and Asia.

There are no independent studies to show whether most Cubans would support foreign military intervention to overthrow the regime that has ruled the island since Fidel Castro and Che Guevara came to power on 1 January 1959. Yet, among those who have left Cuba, many still hope for some change in their homeland.

Echazabal, 29, left Havana with her mother and partner during the Covid pandemic, first heading to Russia, which does not require visas for Cubans for stays of up to 90 days. When legal uncertainties mounted, she flew to Serbia, then made a fraught journey by sea and land – often on foot – through Bosnia, Croatia and Slovenia, followed by Italy and France before finally reaching Spain.

Legal residency remains an uphill battle, made tougher by Spain’s evolving asylum policies. But, despite a deep sense of loss, Echazabal cannot imagine returning to Cuba unless radical change comes. There, daily life is a struggle for basic goods, with failing infrastructure and unviable wages, she says.

For young Cubans, emigration is an “almost universal aspiration” – rooted in persistent hardship and the search for greater opportunity. “From the moment we become aware and start working, all young people want to leave; there’s almost no food, and it’s very hard to get anything,” Echazabal says.

Albizu-Campos says this reality is widespread in what he calls a polycrisis. He observes a harsh “Malthusianism of poverty”, with families forgoing having children to avoid starvation. He considers the constant population decline irreversible, as the “push factors” of economic and political desperation overwhelm any pull to stay. Policy responses, he says, are failing – what he calls a “point of implosion”.

“That erosion is also a response, an act of resistance. ‘I’m leaving. I won’t have children,’ say the young, revealing another survival strategy: they can’t have children because they would starve,” Albizu-Campos says.

The authorities concede there is a reduced population but put the decline at 14%, which would still be the second-worst worldwide during the five-year period to 2025, behind only Ukraine – a country at war.

Cuba’s National Office of Statistics and Information (Onei) counted 9.75 million residents at the end of 2024, down 300,000 from 2023. Onei’s deputy director, Juan Carlos Alfonso Fraga, agrees there has been “a profound, very complicated demographic change”, but avoids the term crisis.

Although his country has faced criticism over the credibility of its statistical data, he says that differences in methodologies – such as who counts as a resident and who counts as a visitor – account for most of the disparities. Cuba’s audits are approved by the UN, he says.

“There is no inconsistency. Cuba has a very solid statistical system,” says Alfonso Fraga. “It is not good for these people to estimate that we are 8 million, that something was overestimated, that mortality was hidden. That is not the case.”

Alfonso Fraga attributes the “demographic challenges” to the US embargo, which has battered Cuba’s finances and trade for more than 60 years.

He compares this outflow to previous emigration crises such as the Mariel boatlift in 1980, when about 125,000 Cubans left Cuba for the US, and the rafter crisis of 1994. “Understanding the damage caused by the blockade to Cuba is very difficult,” he says.

Elaine Acosta González, a sociologist at Florida International University and director of Cuido60 Observatory, has tracked Cuba’s demographic decline, focusing on ageing, migration and the “care crisis”. She says migration has drained the country of the women who most often care for older people.

“Approximately 80% of care, especially for elderly people, is provided by women in the family. If these women leave, who will care for them?” she asks, warning of the erosion of public services, which increases social vulnerability.

“We are experiencing an ongoing deterioration in social welfare,” says Acosta, an exile herself since 1995.

Disillusioned youth

Government and independent experts agree: the economy is at the core of the issue. Cuba faces its gravest economic crisis since the 1959 revolution – worse than the “special period” between 1991 and 1995, after the fall of the Soviet Union.

Official figures show Cuba’s GDP plunged 10.9% in 2020, mostly due to the Covid pandemic and shutdown of international tourism. A feeble recovery brought minor positive growth in 2021 and 2022 – 1.3% and 1.8%, respectively – but the island slipped back into recession in 2023–24. The UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean forecast another 1.5% decline for 2025, putting Cuba alongside Haiti as the only countries in Latin America and the Caribbean in recession.

Of Cuba’s 15 main economic sectors, 11 are in decline: the sugar industry (down by 68% in the five years to 2023), fishing (down 53%) and agriculture (down 52%) lead the list, followed by manufacturing (down 41%), mining, trade, electricity and gas, public administration and social security, social services, science and innovation and financial services. The decline in tourism means foreign exchange earnings have also fallen by 60%.

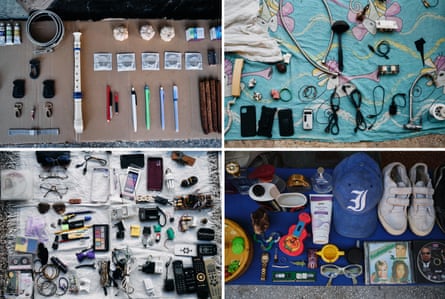

In Havana, poverty is increasingly inescapable. Countless unemployed residents pass the time by informally selling trinkets or offering small services to foreign visitors. Across the capital – as in other major cities – rubbish piles up in the streets due to inadequate waste collection, fuelling sporadic street protests.

In the historic district of Old Havana, a jewel of Latin American colonial architecture, crumbling buildings occasionally collapse – a stark contrast to the luxury hotels the regime has erected to cater to tourists.

Classic 1950s cars, long emblematic of the island, now share the roads with a few imported Mercedes and BMWs, symbols of the widening inequality favouring a small elite of entrepreneurs running state-approved “private” businesses.

Youth disillusionment is evident everywhere, fuelling many young Cubans’ desire to emigrate. Cuadra, 23, graduated in mechanical engineering in Havana only to find that an engineer’s monthly salary – usually about 6,000 or 7,000 pesos (about £12-£14) – is not enough to cover his living expenses.

Instead, using the last family asset – a Soviet-era car with a troublesome engine – Cuadra works as a driver for La Nave, Cuba’s equivalent to Uber. In just one day he is able to make three times his former monthly salary as an engineer.

He is not alone: many graduates are swapping professional careers for any work that helps them save to leave. “If you have the opportunity, you leave – there’s no future here,” says Cuadra, who is working on an application for Spanish citizenship.

“I don’t believe in the revolution – it’s not worth supporting something that doesn’t produce results,” he says.

The ideals of Che Guevara and Fidel Castro, he argues, hold no weight for a new generation facing a starkly divided economy: tourists enjoy dollar-priced stores and better services, while locals contend with shortages and sky-high prices.

Juan Triana Cordoví, an economist at the University of Havana’s Centre for the Study of the Cuban Economy and author of the influential Contrapesos (Counterweight) column, points to both external and internal causes: US sanctions and a stagnant state-focused economic model.

Cuba is enduring a sharp economic decline, low investment, a negative balance of payments, and a phenomenon of “hidden unemployment” – where people have no real reason to work – along with a substantial fall in industrial and agricultural output.

Triana Cordoví decries the government’s heavy spending on tourism infrastructure, noting that over the past 10 years, 35% of total investment has been directed to the construction of “hotels and restaurants” and “real estate and rental activities”, while agriculture, food and energy production have been neglected.

He links the population decline to a brain drain, saying the exodus has emptied classrooms and created shortages of key personnel in hospitals and rural areas. The loss of highly trained professionals has a huge impact, he says. “When you lose an engineer, you lose 22 years of investment. It’s very difficult to recover from that.”

Helen Yaffe, a senior lecturer at Glasgow University who has lived on the island and has family there, argues that Cuba’s current crisis can only be understood within the context of decades of US strategy designed to induce economic hardship and “provoke disenchantment and disaffection”, as laid out in the 1960 Lester Mallory memo – a document widely regarded as the blueprint for the US economic embargo.

These 68 years of sanctions – the most enduring trade embargo in modern history – have deprived Cuba of credit and blocked partnerships with international lenders, while historical allies such as Russia and China no longer offer unlimited financial support due to the island’s crushing public debt (108.6% of GDP) and deficit (about 17% at its peak), as well as its record of defaults on loan repayments.

“It would be almost unbelievable if Cuba didn’t have these crises,” says Yaffe, who hosts the Cuba Analysis podcast. “On the one hand, the blockade creates economic suffering and crises, which then generate emigration, intensifying the demographic crisis.”

Despite impressive scientific breakthroughs, including advanced Alzheimer’s research and a homegrown Covid-19 vaccine, Cuba lacks basic medical supplies, due to the embargo and the economic crisis. Yaffe says the migration-fuelled loss of human capital in healthcare and education is eroding the backbone of Cuba’s social system.

Teams working on development and poverty reduction issues warn that rationed wages, persistent blackouts – up to 22 hours a day in the second-largest city, Santiago de Cuba – and reliance on imports have battered public health, education and transport. Cuba dropped to 97th in the 2025 UN’s human development index, from 57th in 1990.

The baseline for public services was once high, but hospitals and schools are now shadows of their former selves. An economist working in the humanitarian sector says: “For us, the collapse is happening, even though we still have better services than in Central America, for example. The system still exists, but there are no longer resources to make it work.”

Speaking on condition of anonymity, a senior foreign diplomat points to the country’s economic decline, the crisis in the welfare system and the energy deficit, noting that the country produces less than 50% of the electricity it needs. “The collapse has already happened,” he says.

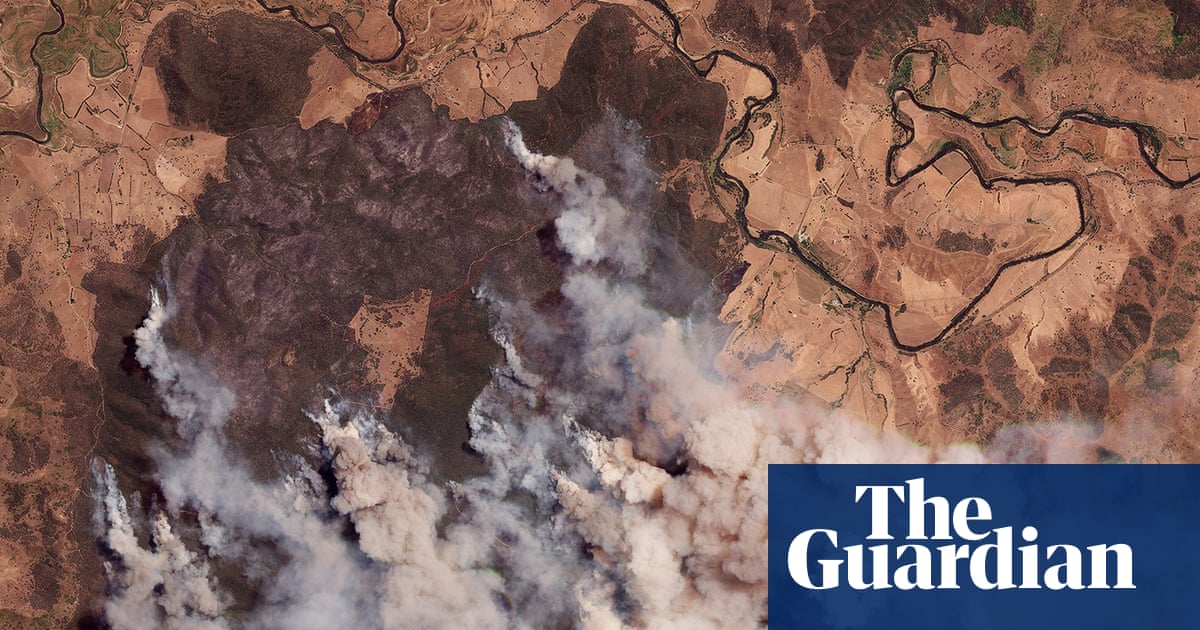

These factors mean that despite Cuba’s minuscule 0.1% share of global cumulative carbon emissions, it faces the risk of a humanitarian disaster due to the climate crisis. Extreme weather events are increasing; Hurricane Melissa, which struck in October, affected more than 3 million Cubans.

“At any moment,” an urban planner warns, “the country could fall into an even deeper crisis, which could come from another crisis, such as a hurricane or something else.”

Dressed in military uniform, following the old Castro tradition, President Miguel Díaz-Canel recently made statements on television praising the civil defence’s response to the damage caused by the hurricane – enraging many Cubans, who are still struggling without power and facing epidemics of Zika virus, dengue and chikungunya.

Despite the evidence, the government denies the risk of a humanitarian crisis. Onei’s Alfonso Fraga says Cuba ranks well in the UN’s multidimensional poverty index, which evaluates income, nutrition, living standards and access to services. The most recent report shows that just 0.1% of Cuba’s population endures severe poverty.

Impasse and unrest

In Havana, it is not easy to find people openly advocating for American intervention in the country. Yet many are calling for change.

Dr Mayra Espina, a researcher at Havana’s Christian Centre for Reflection and Dialogue, calls the crisis structural and systemic. The US embargo, Cuba’s label as a sponsor of terrorism and missteps by Díaz-Canel following Raúl Castro’s retirement – such as failing to carry out reforms that would open up the country’s economy – have all deepened poverty and inequality, she says.

Internal policies and underinvestment have made living and working in rural areas less attractive than in cities, fuelling migration from the countryside and leaving agriculture and food production in decline.

“We are now at a point of no return, as the solution is not to restore previous policies,” Espina says, warning that only significant changes can rebalance the country. “Will they be made? Can they be made peacefully? I don’t know. The situation also involves many risks of violent upheaval.”

Espina says the pandemic hit Cuba very hard, increasing inequality and food insecurity among a growing number of women, and black and mixed-race people.

Cubans’ frustration is sharpest when it comes to healthcare. Once a source of enormous national pride and a model for the region, the system is now buckling under relentless epidemics, worsened by severe shortages of supplies and medical staff.

However, despite living under a dictatorship, criticism is now more open and frequent, not just against the government’s failure to deal with chronic power outages, fuel shortages and the dire state of transport and education, but also about the 67 years of “revolution”.

Some see the regime’s complete collapse as inevitable, while others believe reforms within the only party, the Cuban Communist party (PCC), might save the system.

Carlos Alzugaray, former head of the Cuban mission to the European Union and member of the PCC, acknowledges the challenges the regime encounters in reforming itself.

“They do not know how to design policies to address a reality they do not understand well,” he says, adding that those who want reform face internal opposition from those who are afraid of losing their status. “Many are stuck in a Soviet socialist model that has failed.”

While some believe in reform, others want an end to the communist system. On 11 July 2021, thousands of people took to the streets to protest, in what became known as 11J, urging change as the pandemic and economic collapse converged. Díaz-Canel’s government cracked down, delaying reforms and arresting hundreds.

Human Rights Watch reports that at least 700 people have been imprisoned since the 11J protests, the largest since the Cuban revolution. They face lengthy sentences amid reports of torture, poor conditions and denial of medical care. Despite the “polycrises”, even dissidents acknowledge that the state’s social control apparatus remains robust and vigilant, cracking down on any opposition, detaining possibly thousands of political prisoners.

One of Cuba’s most prominent former political prisoners, José Daniel Ferrer García, the founder of the opposition group Patriotic Union of Cuba (UNPACU), went into exile in Miami in October after decades of activism and multiple imprisonments.

He continues to warn of potential humanitarian disaster, especially in eastern Cuba, where poverty is dire. Ferrer says emigration not only empties offices and hospitals but also weakens the opposition movement at home.

“Most Cubans, inside and outside, want change,” he says. “But you cannot lead opposition inside Cuba because the regime jails any potential organiser immediately.”

Another exiled political dissident, Luis Leonel León, Miami-based director of the Cuban Studies Institute, argues that forced exile has always been the regime’s fix – sending generations abroad and giving rise to what he calls the “empty island”. For many, he says, hope is so diminished that even rebelling seems pointless; the best option is to leave rather than fight.

“In Cuba, people have lost hope. And when you have no hope, you lose the will to live, to do anything, even to rebel,” says León, who believes that while these overlapping crises have created the conditions for regime change, repression and fear are stifling action.

Ferrer agrees, saying that although the country is ripe for rupture, fear drives most Cubans to leave rather than resist. León contends that only a vibrant diaspora, with outside support, such as Trump’s backing for the overthrow of Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela, plus internal fractures in the regime, could bring about regime change.

Also referring to Maduro, Ferrer says: “Advocates of supposed legalistic purity invoke the ‘rules-based international order’. But those rules have been systematically violated by the dictatorships that are now tearing their hair out.”

Ricardo Zúñiga, who was Barack Obama’s principal adviser for the Americas and a key US negotiator during the 2014 thaw between the two countries, doubts that demographic collapse alone would trigger the immediate change that analysts predict. He recalls a fleeting burst of hope as diplomatic ties with Havana were restored, but says the reversal of reforms by both sides disappointed millions.

The abrasive foreign policy of the Trump administration have accelerated the outflow of people, draining the country of its most productive age group and killing hopes for reform.

Zúñiga says the US strategy should aim to improve Cubans’ daily lives, not merely seek regime change. “Worsening conditions have never brought change, regardless of whether sanctions are justified,” he says.

“I believe the popular opposition to [the regime] is quite strong at this point. But people have been predicting ‘next year’ in Havana for a very long time,” he says.

“As long as elites in Havana believe that they will fare worse in a period of change than better, then I don’t see them initiating any sort of palace coup, or adaptation, or movement. And I think that there’s no sign of that.”

Yaffe observes a decline in enthusiasm for the revolutionary ideals of 1959, but insists that, despite real frustration, many Cubans still seek improvement within the system, rather than its revolutionary overthrow.

The man chosen by the regime to comment on the country’s political situation, Guillermo Suárez Borges, a political scientist at Havana’s Centre for International Policy Research, acknowledges the impact of the US embargo in draining the state budget, deterring investment and pushing Cuba to the brink.

Yet he maintains that resilience is ingrained. “Was Cuba at a breaking point after the Soviet collapse? After the socialist bloc vanished?” he asks. “History will tell; people continue to resist.”

Seeing no prospect of the regime’s imminent collapse, Fernández, 35, left Cuba after the 11J protests. During the pandemic, he travelled to Russia in his first attempt to emigrate. From there, he returned to Cuba and tried again, this time flying to Nicaragua, then overland through Honduras and Guatemala to Mexico, on a dangerous route through Central America.

From Mexico, he made it to the US, where he now lives. Free from the threat of censorship and repression, Fernández says he can now testify, without fear, to the motivations, struggles and hopes of his generation of Cuban emigrants – often marked by disillusionment, economic hardship and political repression.

Fernández says the 11J protests made his generation’s discontent and the severity of repression clear. For him, leaving the country is not necessarily a political act, but simply a bid for freedom, dignity and a better life.

“It’s not like the exile of the 1980s and 1990s – that cruder exile. The youth just want to escape from a system, escape from socialism,” he says. “Young people don’t necessarily care much about what is happening in Cuba.”

He contends that the return of Cubans such as him will only be possible with the fall of communism and the creation of what he calls a “true democracy”.

“I’d rather ICE [immigration enforcement agents] pick me up on a street corner of the US and send me … to any country,” says Fernández. “I say sincerely, from the bottom of my heart: return to Cuba? Not even dead.”

14 hours ago

9

14 hours ago

9