The Martin Chivers route from record signing to Tottenham legend was anything but simple. White Hart Lane needed time to learn to love him and Bill Nicholson, who paid Southampton £125,000 in 1968, never understood either the player or the man until years later. Yet it says everything for the curative power of time that the pair walked out arm-in-arm when it came to Billy Nick’s second testimonial against Fiorentina in 2001.

Chivers arrived at Spurs with a headline-grabbing century-plus goals for Southampton. Initially he appeared weighed-down by the fee and the expectation. This was a time when English football was only slowly coming to terms with a “new football” which was abandoning the archetypal battering-ram centre-forward expected to be toe-to-toe with an equally robust centre-half. Chivers stood 6ft 1in yet a firm touch and game intelligence enhanced a deceptive physical strength and eventually contributed to his “Rolls-Royce” aura.

Recall, also, that he arrived in north London in the decade which had opened with the breakthrough of Spurs’ league and cup Double, their attack led by the rambunctious Bobby Smith. The fans were expecting a new Smith to blast open defences so Jimmy Greaves and Alan Gilzean could capitalise.

Ultimately Chivers did deliver but he had to overcome a horrific knee injury only seven months after his transfer. That kept him out for nearly a year before he could build the partnership with Gilzean which proved almost telepathic. Years later, modestly, Chivers would say: “I only scored the goals because Alan told me where to stand.”

No such passivity marked his relationship with Nicholson, who later reflected that Chivers had “the build of a heavyweight boxer but the heart of a poet”. Nicholson and his frustrated coaching staff tried all they could to goad Chivers to greater exertions. Yet Nicholson’s faith in his own judgment in signing Chivers was ultimately rewarded, if not as he had quite expected.

Chivers, in full sail, was a majestic sight. When he seized possession just inside the opposition half and strode majestically forward he was an exhilarating sight for fans, an inspirational one for teammates and an intimidating one for opponents. With cause. In 1971 he provided both goals in the 2-0 League Cup final defeat of Aston Villa, a year later he struck twice in the first leg of the Uefa Cup triumph over Wolves and in 1973 he led Spurs to a year-by-year trophy hat-trick with another League Cup.

A significant factor in Chivers’s maturing as player and leader had been the departure of Greaves for West Ham in 1970. Chivers understood that he was now a senior professional: time for him to step up, take responsibility and, literally, lead from the front.

Chivers left for Switzerland in 1976, his 174 goals in 367 appearances placing him fourth on Tottenham’s all-time scorers’ list, behind only Harry Kane, Greaves and Smith. With Servette he won the Swiss cup and was acclaimed as the league’s best foreign player. He also had time for a private dinner with Nicholson in which the two men brought a greater mutual understanding to the table. Chivers conceded the value of Nicholson’s “tough love” policy while acknowledging that everything in his career to the point of his Tottenham transfer had come too easily, at schools level and then Saints.

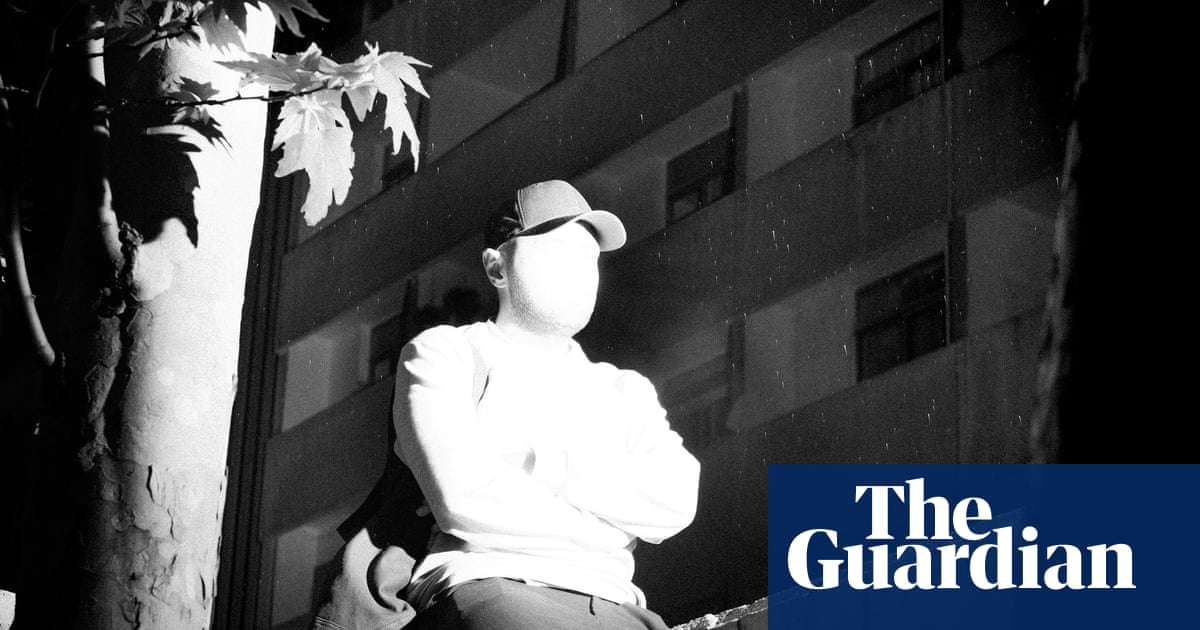

Only later, in the days before the 24-hour prying of social media, were Chivers’s own inner struggles with the stresses of fame to emerge – the self-doubt, tranquilisers before matches to settle his nerves and a superstition about not wearing the No 9 shirt in the days of fixed positional numbers.

In today’s fixture-packed international calendar he would have won far more than 24 caps for England. He scored 13 goals, better than one every two games, before being discarded among the scapegoats for the infamous eliminatory World Cup qualifying draw with Poland in 1973.

Southampton and Tottenham were not the sum total of his English football adventures. There were wind-down stints at Norwich, Brighton and Barnet. He even had a spell as a player-manager at Dorchester Town and in Norway before retiring to “come home” in 1982.

Tottenham welcomed him back. As a club ambassador he was a popular half-time compere, interviewing other former players and encouraging fans in prize-winning competitions including shooting against a crossbar or dribbling between cones then scoring against Chirpy the mascot in goal. He would stride on to the pitch with a cheery and familiar: “Hello, everybody!”

The voice has gone, but the legend lives on.

1 day ago

9

1 day ago

9