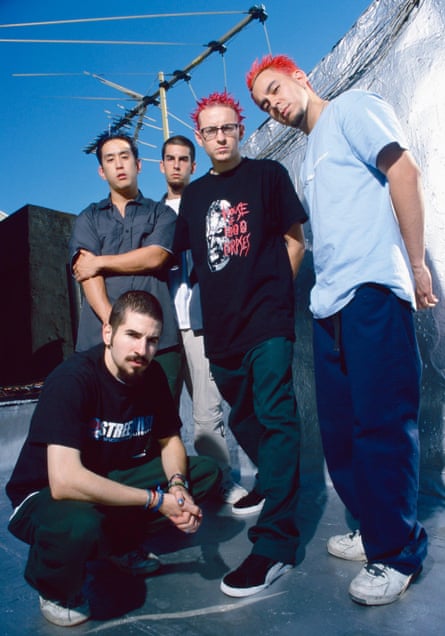

It’s been almost 25 years since Linkin Park released their debut album, Hybrid Theory. An irresistible fusion of metal, hip-hop, electronica, industrial rock and infectious pop melody, it established the Californian sextet as instant nu-metal icons and laid the groundwork for the group to become, by many metrics, the biggest US rock band of this millennium: Hybrid Theory ended up the bestselling album of 2001; its follow-up, Meteora, would also go on to rank as one of the bestselling albums of the 21st century.

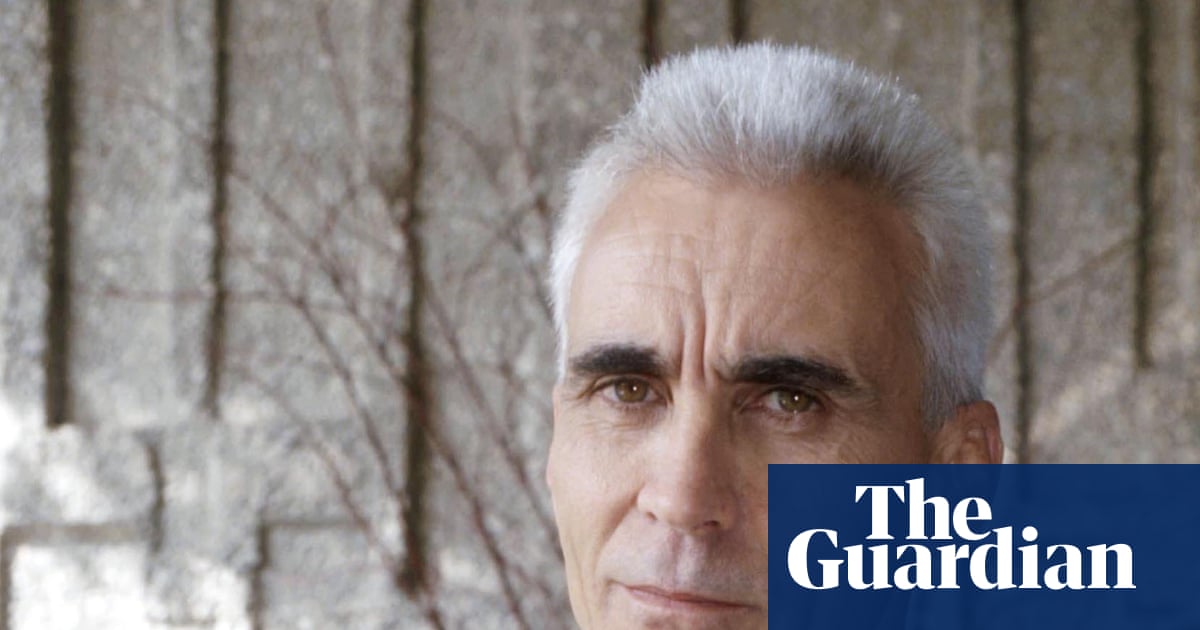

It’s been just 36 hours, however, since the band played their biggest headline gig to date, at a steamy and rapturous Wembley stadium. Outside, it’s still scorching, but in an icily air-conditioned hotel overlooking the Thames, Linkin Park’s co-founder, co-vocalist and chief songwriter, Mike Shinoda, is reflecting on the show. “For any band that’s been around a long time, it’s really easy to start heading into heritage territory,” says the 48-year-old. “You’re just playing that old stuff.”

Linkin Park did of course play the old stuff, crescendoing with a stone-cold triad of belt-along hits – Numb, In the End and Faint – that have 6bn Spotify streams between them. But this was no greatest hits showcase. The band’s eighth album, From Zero – which reached No 1 in 13 countries (including the UK) last November – also received an ecstatic response, and its lead single was one of the very rare hard rock songs to reach the UK Top 5. “This tour and this album are one of our most successful of all time. That, for me, is insane,” marvels Shinoda. “That is way beyond my hopes and dreams for what this whole thing could be.”

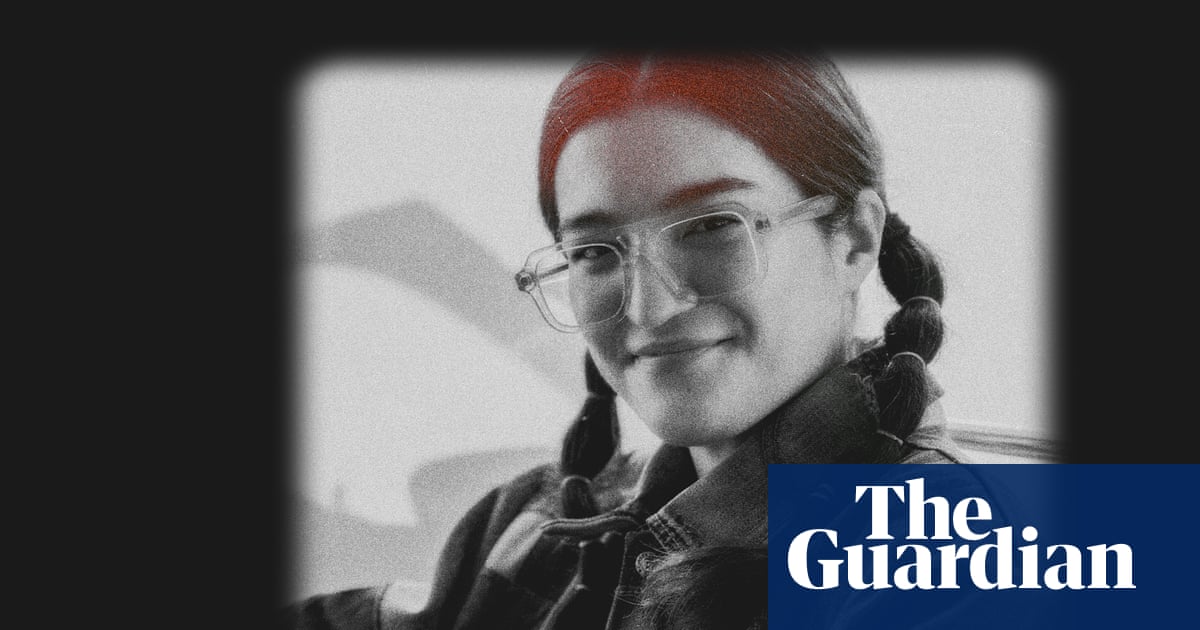

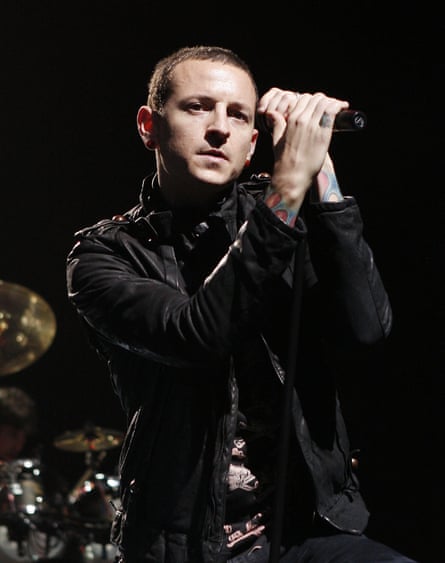

This triumphant second act is all the more miraculous considering Linkin Park are not the band they used to be. In 2017, the group’s lead vocalist, Chester Bennington, took his own life, having struggled with depression and addiction for decades. Sitting next to Shinoda today is 39-year-old Emily Armstrong, who now fronts Linkin Park alongside him (she sings, Shinoda raps).

Bleach-blond hair, dark shades, an acid yellow oversized jersey and a voice that travels from pop croon to gruff, guttural scream: on stage, Armstrong appeared every inch the nu-metal maven. Yet while performing to 75,000 adoring fans would be the ego trip of a lifetime for most rock stars, as Bennington’s replacement, it’s not quite the same. On songs such as the Grammy-winning Crawling, Armstrong’s role was more singalong facilitator than central attraction. “There’s so many fans that have been wanting to see Linkin Park for so long, you know?” she says, brandishing an enormous bottle of electrolyte-orange water. “So I look at it as: this is your moment to sing. And you sing it better than I do at this point!”

After Bennington’s death, Shinoda paused Linkin Park and found refuge in Post Traumatic, a raw and emotional solo album that detailed his struggle to process his grief. Bennington died two months after the release of the band’s seventh album, One More Light, which they were about to take on tour. Shinoda partly “wanted to make Post Traumatic as a diary of how I felt for myself”, but also had the urge to play live “to provide an area for fans to commune and go: ‘Oh, Mike is still here. We didn’t lose everybody.’”

The Post Traumatic tour was cathartic “in the beginning”, he says. “And then towards the end it was exhausting. I had started to … I don’t want to say move on. ‘Move on’ to some people means not looking back and forgetting – that’s completely not how I felt. I felt like I was coping well and I was able to get up in the morning and not think about it, and I was evolving from the terrible stuff that had happened. Then I would go to the show and spend 90 minutes with half the crowd crying. And I’m like, this is fucking exhausting. You know how therapists see patients all day and help them, but then they need therapy themselves? That’s how I felt.”

Shinoda founded Linkin Park at 19, alongside his schoolmates Rob Bourdon (drums) and Brad Delson (guitar). His college friends Dave “Phoenix” Farrell (bass) and the turntablist Joe Hahn joined soon after; Bennington was a later addition after a record label executive insisted they recruit a new vocalist. After Post Traumatic, Shinoda spent the next half-decade figuring out how to bring back the band that had defined his entire adult life. “I sort through information very logically,” he says. He approached the group’s future “from a puzzle-cracking point of view”, he explains, entertaining options like hiring a mini choir for live shows or relying on a rotating cast of famous vocalists.

To begin with, Shinoda invited a few musicians – including some big names, such as the viral soul singer Teddy Swims – down to the studio to write material. He didn’t tell them this was part of a potential Linkin Park comeback, and things could get awkwardly vague. “Two hours into the session, they’d be like: ‘Hey, can I ask you a question? What’s going on here? Who are we writing for?’ And we’d be like: ‘Yeah, we don’t know.’” Sometimes it felt like these collaborators were “angling” to be Linkin Park’s new vocalist. “Like, ‘look how good I can sing!’ It was such a turn-off.”

Armstrong was the tunefully raspy frontwoman of Dead Sara, a bluesy LA punk outfit who were initially hyped (in 2013, Dave Grohl insisted they “should be the next biggest rock band in the world”) but never really made it. She got an invite too. Those sessions never felt like a “Linkin Park tryout”, she says; she was simply “excited to write with Mike Shinoda”.

He laughs: “I love when you use my full name.” The first time she met the band was in 2019, but it wasn’t until she returned to the studio in 2023 that something clicked. Performance and personality-wise, Armstrong – who has sassy little sister energy around Shinoda – seemed like a natural fit.

Shinoda also felt reassured that Armstrong and the drummer Colin Brittain – who replaced Bourdon around the same time – weren’t just using Linkin Park to grow their profiles. “There’s a lot of people for who it’s all about follower count. It’s a very greedy way to live. And these guys aren’t that way.” He appreciates that the pair never took any “sneaky pictures” of Shinoda’s home studio for clout.

“We had a high level of respect,” nods Armstrong, before stifling a smile. “We did have a high level of respect.”

Shinoda looks mock-wistful. “Ah, to go back to those days.”

Armstrong was never going to turn down the opportunity to front Linkin Park. “I’ve been in a band for 20 years and I could only dream of this kind of success,” she says, then makes a face. “That sounded lame.” But she was scared at the prospect of stepping into such big shoes. “Why do I think I can do this?” she wondered, telling Shinoda that she didn’t want to “ruin” Linkin Park. “I’m like, you guys are a legacy band – you guys are so important.”

Shinoda drolly encourages the ego massage: “Oh, go on – tell me more!”

Once the new lineup was complete and From Zero finished (much of it was already written when Armstrong joined the band), it was time to tell the world. The response wasn’t entirely positive. Bennington’s mother said she felt “betrayed” by Shinoda’s decision to reform the band without consulting her, while Bennington’s son expressed dismay at Armstrong’s links to Scientology and her attendance at a hearing in support of Danny Masterson, an actor and Scientologist who was eventually convicted of rape – something that was also widely reported in the press and discussed by fans. I have been told that Armstrong will not discuss Scientology today. She did, however, release a statement at the time, explaining that she had severed all ties with Masterson and condemned his crimes.

Was Armstrong braced for that kind of reaction? “Not this. No, not this,” she says quietly. “I was a little bit naive about it, to be honest.” Even pre-Linkin Park, she tended to avoid social media “for mental-health purposes”, and coped with the clamour by getting offline. “If there was something really, really pressing, I think our PR would talk to us about it. But I’m old enough to know the difference between real life and the internet.”

Shinoda takes a different tack to public criticism, but ends up in the same place. After the Wembley show, he posted a picture of himself in a T-shirt emblazoned with the opening lines of a snide news story about the band’s decision to downsize the venue of their LA show. “There are times when I’m not above being a little petty,” he grins. The T-shirt was “not meant to be mean at all”, he clarifies, and the music outlet in question “are not the only ones who’ve said it. Lots of people have said this band is fumbling: ‘Look how stupid they are, look how bad they’re doing.’ Well, according to the data, we’re not, but you can believe whatever you want to believe.”

When it came to Armstrong, Shinoda felt people’s complaints were also disingenuous. “There were people who lashed out at Emily and it was really because she wasn’t a guy.” Fans, he thinks, were “used to Linkin Park being six guys and the voice of a guy leading this song. They were just so uncomfortable with what it was that they chose a ton of things to complain about. They’re pointing in 10 different directions saying: ‘This is why I’m mad, this is why the band sucks.’”

In the months since Linkin Park 2.0 launched, the reaction from fans has softened and Armstrong has been widely embraced. But devotees are still clearly looking for traces of Bennington in the band’s work. Many interpreted Let You Fade, a bonus track on From Zero’s deluxe edition, as a tribute to the singer, but “it wasn’t written that way,” says Shinoda. “People even pulled out the fact that there’s numbers in the song [that align with] Chester’s birthday. I was like: whoops. That’s not intentional.”

At any rate, From Zero does hark back to the band’s original sound: rock-rap fusion vocals, hip-hop record-scratching, highly accessible melodies and enough gristle (grinding guitar and screaming; anxious and indignant lyrics) to both intensify and offset them. Serendipitously, nu-metal is back in a big way, “thanks to TikTok, the Y2K revival and, of course, enduring teenage angst”, as per the New York Times, with bands such as Deftones enjoying a massive resurgence and acts including Fontaines DC, 100 gecs and Rina Sawayama incorporating the genre into their work.

For millennials such as Armstrong, the sound of nu-metal provides nostalgia-coated comfort. She was a fan in her early teens, and feels “like a child again” when she performs Linkin Park’s old tracks. The era’s garb – voluminous shorts, pulled-up sports socks, chunky jewellery, wraparound sunglasses – is also back in style, which reminds Armstrong of her teen self’s beloved Adidas T-shirt and camouflage combats combo. “We did this first!” she laughs. “I’m old as shit!”

But Shinoda doesn’t look back with rose-tinted spectacles. In the early 2000s, Linkin Park did “a bunch of metal tours and played with Metallica – the energy there was very masculine, bro energy. We were immersed in a culture where it was like an arms race for who could make the most macho music.”

With peers including Korn, Slipknot and System of a Down, the nu-metal cohort was novel and outrageous enough to precipitate a mild moral panic – yet sexist lyrics in the work of groups like Limp Bizkit really were a problem. Linkin Park always seemed less aggressive and intimidating than their peers, and Shinoda always disliked the macho aspect. “Chester connected with it a little more than the rest of us did, but not by much.” His band, he feels, featured “more lyrics that were introspective. It wasn’t like: ‘Hey, I’m gonna kick your ass.’ It was like: ‘Somebody kicked my ass and I’m so frustrated.’ In high school, I wasn’t kicking anybody’s ass. That was not happening.”

Nowadays, nu-metal’s aesthetic has been freed from its more unsavoury elements by a streaming generation who simply don’t remember it; it’s just another fun retro style to rehabilitate. Even Shinoda is less disgusted. “Genres are so blended and music is so all over the place, I don’t hate nu-metal any more.”

Whether down to this defanged nostalgic comeback, the quality of the band’s back catalogue or the incredibly catchy new material, it’s clear from the Wembley show that Linkin Park have a whole new generation of obsessive young fans. The delight in the crowd was palpable – an energy Shinoda is deliberately cultivating, especially after the mental exhaustion of the Post Traumatic tour. “I think we all wanted our show to be really good vibes,” he says. “I want you walking away feeling like, this was such a wonderful, special, fun night.”

Inevitably, this means certain songs are off the setlist. There are a couple that Shinoda would “feel weird playing”, including One More Light, the title track of the band’s last album with Bennington. It was originally written “for a woman at the label that we worked with who passed away. Then after Chester passed, the world decided that it was about him. And so that’s just too sad to play.”

3 months ago

151

3 months ago

151