Survivors of forced adoptions and unmarried mothers’ homes will gather at the first-ever public commemorations of a national scandal affecting hundreds of thousands of British people.

A plaque will be unveiled at noon on Saturday at an open event at Rosemundy, St Agnes, in Cornwall. Meanwhile, in Kendal, Cumbria, on 23 May, a memorial garden will be opened, with attendance by invitation.

Women from across the country, adoptees and relatives are expected to attend the events – at the locations of two former unmarried mothers’ homes – after years of waiting for a formal UK government apology.

There were hundreds of unmarried mothers’ homes operating in the UK between the 1940s and the 1980s. Run by the Church of England, Salvation Army and the Catholic church, working alongside statutory bodies, they promised to protect women and girls from stigma and destitution. Instead, many faced cruelty, neglect and lifelong trauma. Women have described being made to work in punitive regimes and were often pressured into handing over their babies to be rehomed with married couples.

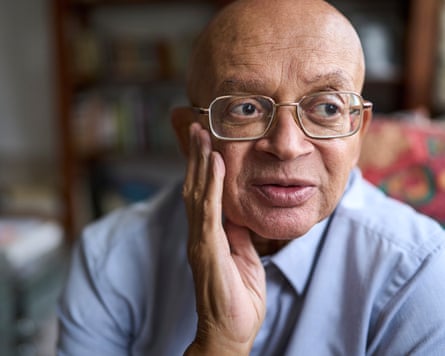

“If the government won’t apologise, at least they can be a point of healing for people,” Phil Frampton, a campaigner from Manchester, said of the commemorative events, which he said were the beginning of “a long-overdue national movement”.

Diana Defries, from the Movement for an Adoption Apology, said: “The significance cannot be overstated. It’s the first time we can stand in front of the cameras and say, it happened here, it happened to all of these people. It will finally be a very public recognition of this injustice.”

Frampton campaigned for the plaque at Rosemundy, where he was born. Facing stigma as the white mother of a mixed-race child in the 1950s, his late mother, Mavis Frampton, was compelled to give him up to the care system and his Nigerian father was removed from the country. Having obtained his own records, Frampton said the system was driven by a desire to keep welfare costs down as well as “rotten” societal prejudices.

Lyn Rodden, from Camborne, faced “non-stop” pressure to give her baby up at Rosemundy, where she was among teenagers subjected to unpaid labour, even after her waters had broken.

“We were literally slaves to them, it didn’t matter what condition we were in. People think that it was only in Ireland and it was never like it over here – it damn well was,” she said.

The 88-year-old, reunited with her son in adulthood after years of their lives “crisscrossing”, said the Rosemundy plaque means “everything … because so many people called me a liar”.

In further evidence of the devastating impact of the forced adoptions system, research by Michael Lambert, of Lancaster University, has indicated the use of the lactation-suppressing drug diethylstilbestrol, which has been linked to an increased risk of cancers, in some unmarried mothers’ homes, while an ITV investigation has revealed unmarked graves across England contain the bodies of babies who did not survive.

Steve Hindley, 79, from Salford, campaigned for the Kendal memorial garden near the former St Monica’s home, where his late wife, Judy Hindley, was sent, aged 17, in 1963, before they met.

Traumatised Judy took her life in 2006, near Parkside cemetery, Kendal, where babies including her 11-week-old son Stephen were buried in unmarked graves. Stephen had been denied care for hydrocephalus and spina bifida.

The Parkside cemetery memorial, Hindley said, would provide “dignity at last” for the babies.

A 2021 parliamentary inquiry found there were 185,000 adoptions involving unmarried mothers in England and Wales between 1949 and 1973 alone, based on “re-registrations” of babies “born out of wedlock”, and that the state was ultimately responsible for the suffering caused by public institutions and employees involved.

Scottish and Welsh governments have formally apologised, but the UK government refused the recommendation of a formal apology in 2023, and has not provided one since Keir Starmer took office.

Meanwhile, the Church of England has expressed “great regret”, the Catholic church has apologised and the Salvation Army has said it was “deeply sorry”.

A Department for Education spokesperson said: “This abhorrent practice should never have taken place and our deepest sympathies are with all those affected … we take this issue extremely seriously.”

8 hours ago

5

8 hours ago

5