In the summer of 1970, a group of aspirant revolutionaries arrived in Jordan from West Germany. They sought military training though they had barely handled weapons before. They sought a guerrilla war in the streets of Europe, but had never done anything more than light a fire in a deserted department store. They sought the spurious glamour that spending time with a Palestinian armed group could confer. Above all, they sought a safe place where they could hide and plan.

Some of the group had flown to Beirut on a direct flight from communist-run East Berlin. The better known members – Ulrike Meinhof, a prominent leftwing journalist, and two convicted arsonists called Gudrun Ensslin and Andreas Baader – had faced a more complicated journey. First, they’d had to cross into East Germany, then they took a train to Prague, where they boarded a plane to Lebanon. From Beirut, a taxi took them east across the mountains into Syria. Finally, they drove south from Damascus into Jordan.

They were not the first such visitors. Among the broad coalition of activists and protest groups known as the New Left, commitment to the Palestinian cause had become a test of one’s ideological credentials. Israel was no longer seen as a beleaguered outpost of progressive values surrounded by despotic regimes dedicated to its destruction. After its victory in the 1967 war and subsequent occupation of Gaza and the West Bank, Israel was now frequently described by leftists as a bellicose outpost of imperialism, capitalism and colonialism. At the same time, many intellectuals on the left had come to believe that the radical transformation they longed for would never begin in Europe, where the proletariat appeared more interested in foreign holidays and saving up for fridges or cars than manning the barricades. Instead, they believed, the coming revolution would originate in Asia or Africa or Latin America, where the masses were ready to rise up and fight.

The question was where to go. Unlike in Vietnam or Latin America, the Palestinian cause was one where direct involvement was both feasible and relatively risk-free. The Middle East was only a short flight or a cheap bus and boat trip away, and until the autumn of 1970, the worst that could be expected when one returned home would be some slightly difficult questions at border control.

So they came, and in increasing numbers. A single camp north of Amman run by Fatah, the largest of the Palestinian armed factions that were active at the time, welcomed between 150 and 200 young volunteers in 1969 and 1970. The biggest contingent was British, though most western European countries were represented, along with some eastern Europeans and several Indians. These were an ideologically eclectic bunch. When in February 1970 the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine, one of the smaller armed factions, offered training and instruction to any “revolutionary and progressive forces” who wanted to build a “world front against imperialism, Zionism and reaction”, about 50 “militant Maoists, Trotskyites and members of … an extreme leftwing group in France” responded, according to the FBI. Most merely toured refugee camps, worked on farms, helped dig trenches and assisted at clinics. Some fired a few rounds from a Kalashnikov. Then “they picked up their [keffiyeh] headdress, several volumes of Palestinian poetry and went home souvenired and sun-tanned”, in the words of one foreign correspondent.

The group that arrived in Amman from West Berlin in June 1970 was an odd assortment of violent activists, polemicists, self-publicists, adventurers and intellectuals. Their leader, though not the loudest or best-known among them, was Gudrun Ensslin, the 30-year-old daughter of a Protestant pastor. Tall, fair and serious, she had been brought up in a small village in an environment of strict moralism. There was no sign of any rebellion in her youthful years, only of a fierce intelligence. She won a scholarship to Berlin’s Free University to study for a doctorate in literature. She campaigned for the moderately leftwing Social Democrat party (SPD) in elections in 1965 and, like many others, felt deeply betrayed when the party entered government in coalition with conservatives the following year.

A turning point for Ensslin came in June 1967, when Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, the shah of Iran and a staunch US ally, visited West Germany, sparking major protests. The shah’s security men attacked the demonstrators in West Berlin and a local policeman shot dead a student. Immediately afterwards Ensslin told fellow activists that it was impossible to reason with “the generation that made Auschwitz” and that only violence could halt a government set on establishing a new authoritarian regime.

As protests intensified across West Germany, Ensslin reached a moment of crisis. She left her infant son and his father, a fellow literature student, and dived deep into the world of radical activism in West Berlin. There, among the drifters, pranksters, runaways, petty criminals, draft dodgers, potheads, avant garde artists and the occasional ideologue who made the city such an exciting, anarchic place, she met Andreas Baader, with whom she fell in love.

Baader was 24 years old. His father had disappeared on the Russian front during the second world war and Baader had grown up surrounded by bereaved women. A first brush with the police when he was nine was followed by expulsion from a series of educational establishments and a short time at art school. Formal study of any kind bored Baader; he was briefly involved in experimental “action-theatre”. He was, a friend said, “a Marlon Brando type”.

Spoiled, arrogant and lazy but with a brooding, scruffy charm, Baader appealed to women, and some men too. He dressed fashionably and expensively, posed for erotic pictures for a gay men’s magazine, and occasionally wore makeup. Fast cars held a powerful appeal though obtaining a driving licence did not, resulting in a string of convictions for traffic offences. Baader was uninterested in politics and unmoved by progressive causes. He was attracted to Berlin primarily because residence there meant exemption from military service.

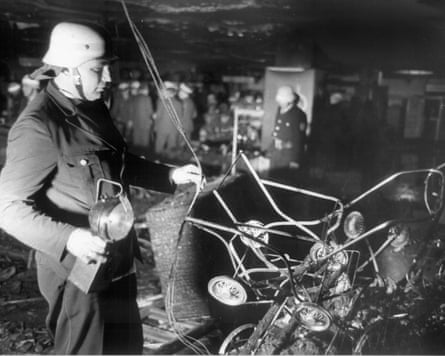

Many Berlin activists found Baader profoundly irritating. One described him as “impossible to talk to”, prone to sulking, a bully and a braggart. In April 1968, an accidental fire in a department store in Brussels killed more than 250 people. Baader boasted of his intention to bring about a similar conflagration, but it was Ensslin who organised a car, obtained the necessary equipment and selected a multistorey department store in Frankfurt as their target. After the attack, which caused substantial damage but no loss of life, she and Baader headed to a well-known leftist bar to celebrate loudly. This was an error. So too was leaving bomb components in the car and a list of ingredients in a coat pocket.

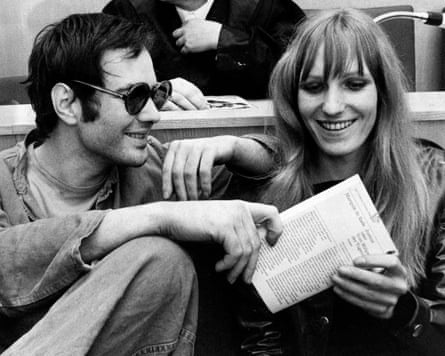

The mistakes made by Ensslin and Baader in Frankfurt led to their arrest within 36 hours. In October 1968, after six months in custody, they faced trial. In court, Ensslin, wearing a red leather jacket, waved a copy of Mao’s Little Red Book and claimed that the arson had been a protest against the failure of the German people to react to the horrors of the Vietnam war. Baader, wearing dark glasses, a T-shirt and Mao jacket, smoked a Cuban cigar in the dock and described students in Germany as the country’s equivalent of oppressed Black Americans. They each received three-year prison sentences but were released eight months later pending appeal.

A condition of their provisional liberty was that they devote it to worthy social causes, so the following months were spent working with teenagers in institutions in Frankfurt. Ensslin organised sessions to discuss Mao. Baader appropriated the youths’ financial allowance, took them to bars, drank and lectured them about the coming revolution.

When they heard that their appeal had been rejected, Baader and Ensslin fled rather than return to prison. They drove west to Paris where they stayed in the spectacular apartment of a radical French writer, enjoyed some lavish restaurant meals and photographed each other in cafes. When, after several weeks, the city’s charms palled, the couple drove to Italy. In Milan, Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, the wealthy leftwing publisher, welcomed them to his home and laid out his collection of guns for their admiration. There were long conversations about the forthcoming armed struggle. When their car was stolen, Baader broke into an Alfa Romeo which they drove back to Berlin. In need of somewhere to stay, they sought out the journalist Ulrike Meinhof, whom they had met when she had reported on their trial.

Meinhof was almost a decade older than both. She had grown up in a small, conservative town in north-west Germany, a conscientious, mature, religious and idealistic young woman who won a scholarship for exceptionally gifted students to study pedagogy and psychology at university. She campaigned against the stationing of nuclear weapons in West Germany, joined the youth organisation of the Social Democratic party, listened to jazz and smoked a pipe.

At this time she began to publish articles in student magazines. Her opinions were radical but not extreme; her arguments structured and well researched. She was soon writing regularly for Konkret, a leftwing magazine of culture and politics based in Hamburg. In 1961, she married Konkret’s publisher and gave birth to twin girls a year later. Over the following years, Meinhof’s journalism earned her respect, a good income, a few lawsuits and a new status as an unofficial spokesperson for the emerging protest movement in West Germany. She made frequent appearances on television and radio. A slightly smitten British correspondent interviewed her at home in Hamburg, and described “a nervous, pretty woman with two blond little girls rolling round her feet” who sadly confessed that other more militant activists dismissed her as a “peace-loving pancake”.

But Meinhof was not happy. For many years, she and her publisher husband had been part of the local liberal social elite, invited to dances and dinner parties and spending their weekends at a fashionable coastal resort of Kampen, on the island of Sylt in the North Sea. This lifestyle filled her with unease. “Our house, the parties, Kampen, all of that is only partly enjoyable … TV appearances, contacts, the attention I get … I find it pleasant, but it doesn’t satisfy my need for warmth, solidarity, belonging to a group,” she wrote in her diary.

Luckily for Ensslin and Baader, Meinhof eventually resolved the tension between her deepening ideological commitment and her lifestyle. In late 1967 she had divorced her unapologetically unfaithful husband and moved with her daughters to Berlin, where her apartment became a meeting place for activists, writers, students and young people on the run. When the two fugitive arsonists knocked on her door on their return from Italy, she agreed to let them stay.

By 1969, Meinhof’s relatively moderate views had become more extreme, the language harsher, the arguments more direct. She was very busy, lecturing while also working hard on an investigation into young female runaways in state institutions, writing late into the night and early morning. Interviewers found her tense and angry, her already deep voice made harsh by chain smoking.

“Protest is when I say I don’t like this. Resistance is when I put an end to what I don’t like. Protest is when I say I refuse to go along with this any more. Resistance is when I make sure everybody else stops going along too,” she wrote, in what would be one of her last columns in Konkret in April 1969.

Ensslin and Baader lived with Meinhof for several weeks, an intense experience for everyone concerned. Meinhof’s daughters liked Ensslin, who played with them, but disliked Baader, who laughed when they hurt themselves. After a couple of months the guests moved on, but Meinhof was still unhappy. When Meinhof’s new partner proposed a Christmas tree, she accused him of bourgeois sentimentality and banned presents or any celebrations. Her daughters frequently missed school. Meinhof told collaborators she couldn’t see the point of journalism any more, but also railed against the restrictions imposed on her by motherhood.

When Baader was re-arrested, driving a stolen car with false papers, and returned behind bars to serve out the rest of his sentence, Ensslin asked Meinhof to help her lover escape. The journalist agreed to write letters to the governor of the prison describing a book project that she was to undertake with Baader and so obtained permission for him to join her for research in a Berlin library. At about 10am on 14 May 1970, shortly after Meinhof and the prisoner had settled down with cigarettes and instant coffee in the reading room of the Institute of Social Issues, two women gained entry, then let in a man armed with a Beretta pistol, then Ensslin. Together, they overpowered the two armed prison guards with teargas and shot an elderly member of staff. Baader jumped from a first-floor window on to the institute’s well-tended lawn and ran. Meinhof faced a split-second decision: stay where she was, pretend to have been duped by Ensslin and so return to her writing, activism and children. Or follow Baader and the others and exchange all this for an uncertain and dangerous life as a wanted criminal on the run.

A stolen Alfa Romeo sports car had been prepared for their getaway – later found by police with a teargas gun and an introduction to Marx’s Das Kapital inside – but the bloodshed during the raid required a change of plan: now they would need to get further away than a single tank of petrol would take them. To complicate matters even more, Meinhof had chosen to follow Baader through the window and they now had a well-known public figure among them. Meinhof had no support network or false papers, and was encumbered by family commitments. One of the first things she did as a fugitive was to call a friend to arrange for her daughters to be picked up from school.

The obvious solution was to leave West Germany, and ideally Europe too. Ensslin was in touch with the representative of Fatah in West Berlin who was able to organise a hurried departure. Clutching forged passports and amateurishly disguised with wigs and makeup, they assembled at Berlin’s Friedrichstrasse station just over three weeks after Baader’s escape and set out for the Middle East.

After the chaos and excitement of the journey from West Berlin, Amman initially proved something of a disappointment. Their Fatah hosts had set up the standard itinerary offered to such visitors, but Baader, Ensslin, Meinhof and the half-dozen others who had accompanied them were not particularly interested in viewing clinics, villages and refugee camps. They had not come as tourists, they told their hosts, they wanted instruction in guerrilla warfare.

Despite some misgivings, a senior Fatah official called Abu Hassan agreed to their request and sent the group to a training camp in the hills outside the Jordanian capital. Its two stone buildings, shooting range, dirt exercise yard and threadbare tents were guarded by Palestinian fighters and ringed by barbed wire fences. The trainees were issued Kalashnikovs, a rare honour.

The following weeks could not be described as an unqualified success. Fatah instructors taught the Germans how to build incendiary bombs and other explosive devices, as well as how to rob a bank. But none of the volunteers was physically fit or knew anything about guns or explosives. When they had launched the operation to free their leader a month earlier, they had been obliged to hire an experienced criminal to carry the one lethal weapon and at least one of their number had vomited from nerves. Baader now refused to give up his tight velvet trousers even on an assault course, and Meinhof struggled with the physically demanding aspects of their training.

Almost immediately there was a series of fierce disagreements between the Germans and the middle-aged Algerian who ran the camp, a veteran of the independence struggle against the French. The first of these was about Ensslin and Baader’s insistence that they be allowed to sleep together, which was unheard of in the conservative environment of Fatah’s training camps. The visitors complained about the diet. Then the women insisted on sunbathing either nude or topless, which provoked further outrage.

A limit was placed on the ammunition that trainees could expend after they fired off hundreds of precious rounds with apparent abandon, and Baader, who frequently refused to follow orders, led the trainees in protest. Abu Hassan returned to calm tempers once again, but just when peace had been restored and a chicken slaughtered and cooked in his honour, Baader complained that it was unfair and “unrevolutionary” that a leader might receive better food than ordinary foot soldiers.

Such tensions and mutual incomprehension were to be expected. Almost none of the visitors spoke Arabic and very few had travelled in the Middle East, or even overseas, before. For all their sympathy for the Palestinians’ grievances and enthusiasm for their cause, the European volunteers were profoundly ignorant of the society, history and culture of their hosts. A Fatah official later remembered that their guests’ interest in the Palestinian cause appeared “very recent indeed”. A group of British International Socialists smuggled alcohol into one training camp, got drunk, held an impromptu sing-song and then got into a fight, first with a group of British Maoists then with the guards who tried to confiscate their remaining bottles. Another group of volunteers refused to join in with the trainees digging trenches, only to leap into those very holes when an Israeli jet flew low over the camp.

The group that Baader, Ensslin and Meinhof had led to Jordan was particularly vexatious. In early August, after seven weeks in Jordan, Baader provoked another argument by demanding to be treated as a militant commander equal in status to Abu Hassan, who was a senior intelligence official and a protege of Fatah’s founder and leader, Yasser Arafat. Shortly afterwards, Ensslin demanded that the Palestinians execute a member of her own group whom she suspected of being an Israeli spy, largely because he had listened to a Hebrew-language broadcast on a transistor radio. Abu Hassan’s polite refusal led to a new confrontation. This time Baader, Ensslin and the others were told that arrangements would be made for their swift return home.

Three days before they had left Berlin, the half-dozen young men and women who had been involved in Baader’s escape had issued a communique, printed in a leftist magazine. It promised a campaign of violence to bring the latent conflict in Germany into the open and promised to “start [in Germany] what has already started in Vietnam, Palestine, Guatemala, in Oakland and Watts, in Cuba and China, in Angola and New York”. The statement did not attempt to explain the group’s actions “to the intellectual windbags, the know-it-alls and the shitting- in-their-pants brigade”, nor to the “petit bourgeois intellectuals” or “lefty ass-kissers”. Instead, its message was meant for the “potentially revolutionary segment of the population”: the underpaid workers, the teenage girls in institutions, the boys in care homes, the factory workers, the families on the housing projects, the labourers and apprentices, all those who were “exploited but receive no compensation in the form of good living standards, consumption, loans, automobiles”.

The statement, probably written by Meinhof though signed by Ensslin, appeared under an image of a leaping black panther that was clearly inspired by the US activists they most admired. It ended with a series of lapidary exhortations: “Don’t go meekly off to slaughter … The end of the rule of the pigs is in sight! … Develop the class struggle. Organise the proletariat. Start the armed resistance.” The statement was titled: “It is time to build up the Red Army Faction.”

But launching an armed struggle in Germany proved more difficult than Ensslin, Baader and Meinhof anticipated. The name they had chosen for their group reflected their belief that theirs was merely one of many efforts worldwide that would collectively bring about the downfall of capitalist, imperialist states such as the US and West Germany. But the reality was that some parts of the world were significantly more receptive to revolution than others. By the late spring of 1971, the group had been back in Germany for eight months, and yet had little to show for its efforts beyond a dozen or so bank robberies.

In reality, life for Red Army Faction (RAF) members was mainly dull, stressful and frustrating, punctuated by infrequent moments of fear or great excitement. “You join the urban guerrillas and then you find yourself spending a month fixing up an apartment, and there’s always shopping to be done, things that are needed. That’s 99% of what goes on,” one remembered later. Another described tedious hours spent encoding and decoding addresses and messages. Errors could have serious consequences, though. Meinhof miswrote an address after she and three other RAF members broke into a town hall to steal blank identity cards and all the precious documents were sent to the wrong location and lost. Funds often ran low. Meinhof’s wealthy leftwing friends donated money and offered their weekend homes as temporary hideouts, but food was sometimes scarce and safe houses could be uncomfortable and cold.

Their camaraderie helped ease the discomfort. “They debated, laughed, and joked with one another … They all loved Donald Duck comic books and read them together, laughing like children. Andreas and Gudrun often fooled around, giggling like teenagers. If four or five of them were there, and they had time, they cooked together,” wrote Margrit Schiller, a young recruit. She had never met people like Baader, Meinhof and Ensslin before. “Their political discussions, the way they handled weapons, their jokes, how they spoke to and treated one another. They seemed to be connected, to be on the same wavelength, almost as if they shared one mind.”

Music and film provided diversion, too. Meinhof was ashamed of her fondness for the music of Rod Stewart. Baader had no such qualms about his taste in film, modelling himself on the anti-heroes of contemporary gangster films and wearing a trenchcoat and hat in imitation of the leading men of the nouvelle vague. In Jordan, when Ensslin had decided one of their group was a spy, Baader initially proposed that he, she and Meinhof shoot the suspect from different directions so no one would know who had fired the fatal shot. He drew the idea from a spaghetti western. A triple bank robbery was inspired by Gillo Pontecorvo’s 1966 film, The Battle of Algiers.

The RAF stole many vehicles, but the small, fast BMW 2002 was such a favourite that owners across Germany placed stickers on their windscreens saying “I am not a member of the RAF” and joked that BMW actually stood for Baader Meinhof Wagen. Baader preferred top-of-the-range sports cars. In the autumn of 1971, he crashed a stolen Porsche 911 at more than 100mph on an autobahn, emerging from the wrecked vehicle without a scratch.

Ensslin tolerated her lover’s behaviour but was deeply irritated by her male comrades’ tendency to be more interested in sex than overthrowing capitalism. During a visit to the famous Kommune 2 in Berlin in the summer of 1971, she upbraided a leading local activist for “chasing round apartments, fucking little girls, smoking hashish”, angrily telling him that such activities were a distraction from the serious work of the armed struggle.

In October 1971, the RAF committed its first murder. Two members in Hamburg shot a police officer who was attempting to arrest a third. The killing was barely discussed within the group, but it marked the start of a new and more violent phase of activity. A second policeman was killed during yet another bank robbery, then a third. Authorities responded with a series of vast dragnets that met with little success but did hinder the group’s ability to move freely.

Eight months later, in April 1972, the RAF’s leaders decided that the moment had come to launch the blow that would, by provoking massive repression and revealing the “fascist” nature of the German state, definitively rupture the “false consciousness” of the working classes and so create the conditions for revolution. As ever, quite how to do this was unclear. When it was reported in the news that the US air force, engaged for several weeks in a massive bombing campaign in North Vietnam, had dropped mines to block the country’s principal port, Ensslin suggested bombing the numerous US military installations in West Germany in response. Baader’s response was typically unconsidered: “Let’s go then.”

The first target of this new campaign was the sprawling US base outside Frankfurt. The bomb they planted demolished part of the officers’ mess, killing an officer. They then released a communique. Written by Meinhof, it ended with Che Guevara’s call for revolutionaries worldwide to create “two, three, many Vietnams”. The RAF’s next effort wounded five at a police headquarters in Augsburg, and was swiftly followed by an abortive attempt to kill a federal judge. After a brief pause, a bomb was planted at the head office of the conservative newspaper group Springer, long a focus of antipathy among the German left. Their warning was ignored, and when the bomb exploded it injured dozens.

Surprised by the public disgust this prompted, Baader telephoned Meinhof, who had overseen the attack, to berate her for her “stupidity” and ordered the group to revert to military targets. On 24 May the group stole two cars, placed a bomb in each with a timing device and drove them into the headquarters of the US army in Europe at Heidelberg. This attack killed three soldiers. Meinhof once more issued a statement, equating the US air offensive in Vietnam with the Allied bombing of Germany during the second world war, and saying that its further intensification would be “genocide, the final solution, Auschwitz”. Then, with its stock of pipebombs and its appetite for violence momentarily exhausted, the RAF rested.

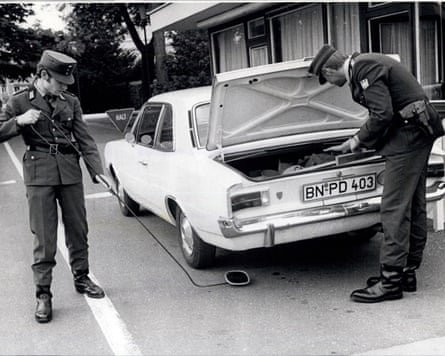

Some days after the attack in Heidelberg, police in Frankfurt were told by a resident about a garage on the outskirts of the city where men arrived at odd times of the day and night to work with some kind of powder stored in large sacks. Very early on the morning of 1 June, police officers hiding nearby watched a Porsche Targa drive the wrong way up a one-way street and come to a stop. Baader and Holger Meins, a former art student and film-maker who was close to the principal leaders of the RAF, got out and went to the garage. Police moved in.

Meins eventually gave himself up when an armoured car was deployed, but Baader continued to shout abuse and shoot until he was hit in the thigh by a police sniper. TV footage showed him being carried on a stretcher to a police van, grimacing in pain, his dark hair dyed a lurid shade of orange. In the garage, police found explosives and a silver-grey ISO Rivolta, one of the most expensive and rare sports cars in Europe, stolen by Baader some weeks before.

Authorities now set about rounding up the rest of the group. The next RAF leader to be caught was Ensslin, who was arrested in a high street store in Hamburg after leaving a coat with a revolver in its pocket outside a fitting room as she tried on some sweaters. A shop assistant noted its weight, checked the pockets, found the gun and called the police. “I am glad that the hunt is now over,” her father told journalists.

That left Meinhof still at liberty. But the violence of the previous weeks had alienated – or at least scared – many who had once been sympathetic to the RAF. Twelve days after the arrest of Baader, when a young teacher in Hanover was asked by an intermediary if he would allow two unidentified people to stay the night, he hesitated, spoke to his girlfriend, and made a phone call. When the police arrived they found a poster of Guevara on the sitting room wall, bags containing guns and a bomb, and Meinhof, underweight and exhausted, who offered no resistance whatsoever. The revolutionary campaign of the RAF’s first generation, as they would become known, was over.

With the founder members in jail, a new generation of RAF members moved to the forefront. Though still nominally committed to global revolution, their only real goal was to liberate their leaders. In this, they were unsuccessful. In 1976 Meinhof, who had suffered weeks of solitary confinement and sensory deprivation, killed herself in her cell in Stammheim high security prison. In the months before she died, the former journalist had been bitterly and repeatedly criticised by Ensslin and Baader in statements circulated among RAF prisoners and followers.

A year later, after the two remaining leaders had given an ultimatum to their followers to free them before they made their own desperate efforts to break out, the group launched a campaign of spectacular violence. It climaxed with the abduction of one of the country’s best-known industrialists and then, when the government of Helmut Schmidt refused to make any concessions, the hijacking of a Lufthansa passenger jet in Mallorca, which was eventually flown to Somalia. This final effort ended when a team of West German police commandos stormed the plane, killing all the attackers and freeing the hostages without loss. When they heard the news on a clandestine radio system rigged in their cells, Ensslin and Baader killed themselves.

In Baghdad, a temporary base, a dozen or so RAF members gathered in shock in the offices of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, which had carried out the hijacking on the group’s behalf. Many wept, others made wild and entirely unrealistic plans for revenge. Brigitte Mohnhaupt, the uncompromising 28-year-old former philosophy student who now took over the leadership of the RAF, did neither. The suicides were “eine Aktion” – an operation – she insisted. “They were not victims and never were,” Mohnhaupt told the others. “You don’t get made a victim, you have to make yourself a victim. They were in charge of their own situation until the last minute. What does this mean? They did it to themselves, not that it was done to them. Stop crying, assholes.”

Adapted from The Revolutionists: The Story of the Extremists who Hijacked the 1970s, published on 2 October by Bodley Head and available to order atguardianbookshop.com

3 months ago

131

3 months ago

131